by Carol A Westbrook

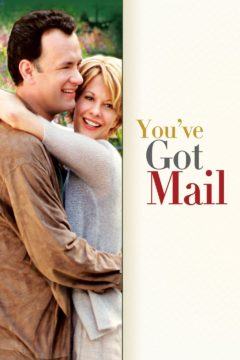

There was a time when getting an email was a rare event, a special event. Remember the 1998 film, “You’ve got mail,” in which Meg Ryan meets Tom Hanks in an online chatroom? Not recognizing that they are business rivals, they eventually fall in love, in what is perhaps the first online romance. Email was still a novelty in 1998, since mail programs had only been around for a couple of years, and the world wide web itself had only been available for 6 years.

That was then. Now, there are over 200 unsolicited emails coming into my mailboxes each day–so many that I can’t find the ones from my friends or colleagues amid the mess. And due to my junk mail filter–a necessity nowadays–I risk missing e-bills and important notices. Amid this mess, so many of my friends have just stopped using email that I can’t be sure that a message I send will be read. I have to reach them by other methods, sometimes text or Instant Message, an even old-fashioned phone call!

What happened to email? Spam happened. Read more »

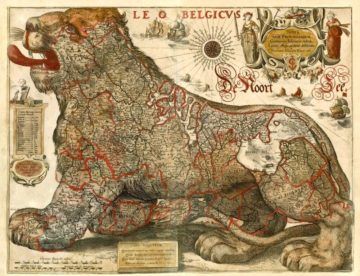

In 1987 I had a sort-of-girlfriend, let us call her Nikki, who came from a devout Catholic working-class family of French-Canadian heritage. When I met her she had just returned from a family pilgrimage to Medjugorje, in post-Tito, pre-war Yugoslavia, where her mother and father had hoped to see the famed weeping statue of Mary, fluentis lacrimis. I knew enough of Slavic etymology already to be intrigued by that town’s name, like the young W. V. O. Quine, who once found himself on a street in Prague that started with the preposition Pod, and thought: “I must be at the bottom of something”. The Medju clearly meant the place was between or amidst something or other, but what exactly?

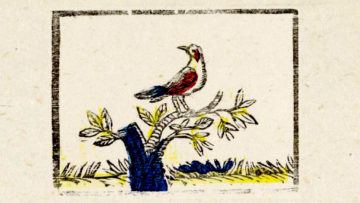

In 1987 I had a sort-of-girlfriend, let us call her Nikki, who came from a devout Catholic working-class family of French-Canadian heritage. When I met her she had just returned from a family pilgrimage to Medjugorje, in post-Tito, pre-war Yugoslavia, where her mother and father had hoped to see the famed weeping statue of Mary, fluentis lacrimis. I knew enough of Slavic etymology already to be intrigued by that town’s name, like the young W. V. O. Quine, who once found himself on a street in Prague that started with the preposition Pod, and thought: “I must be at the bottom of something”. The Medju clearly meant the place was between or amidst something or other, but what exactly?  Last winter, Ray Harinarain, a heating and air-conditioning contractor living in Brooklyn, flew home to Guyana with several thousand dollars in cash. Escorted by armed guards, he drove from village to village, examining wild finches like some veterinary talent scout. The birds had been captured in nearby forests using glue strips or nets. Some were visibly frightened by life in captivity. A few had begun the halting process of habituation, waiting on their perches instead of bashing against the bars. And the “baddest” birds—which in Guyanese patois means the best birds—were just about ready to burst into song.

Last winter, Ray Harinarain, a heating and air-conditioning contractor living in Brooklyn, flew home to Guyana with several thousand dollars in cash. Escorted by armed guards, he drove from village to village, examining wild finches like some veterinary talent scout. The birds had been captured in nearby forests using glue strips or nets. Some were visibly frightened by life in captivity. A few had begun the halting process of habituation, waiting on their perches instead of bashing against the bars. And the “baddest” birds—which in Guyanese patois means the best birds—were just about ready to burst into song. A good many people claim to be “free speech absolutists,” but I’m not sure whether they really are. Push an absolutist hard enough with edge cases and you typically discover that they do indeed draw lines beyond which speech may not be permitted to go. (How many celebrants of free speech advocate the elimination of libel and slander laws?) But even if true absolutists exist, some of the people most often cited in support of free speech certainly were not so absolute. And there may be useful lessons for us in that.

A good many people claim to be “free speech absolutists,” but I’m not sure whether they really are. Push an absolutist hard enough with edge cases and you typically discover that they do indeed draw lines beyond which speech may not be permitted to go. (How many celebrants of free speech advocate the elimination of libel and slander laws?) But even if true absolutists exist, some of the people most often cited in support of free speech certainly were not so absolute. And there may be useful lessons for us in that. Arefa Johari was

Arefa Johari was Flash forward to the present day, as the art of cinema is being systematically devalued, sidelined, demeaned, and reduced to its lowest common denominator, “content.”

Flash forward to the present day, as the art of cinema is being systematically devalued, sidelined, demeaned, and reduced to its lowest common denominator, “content.” Dalton is one

Dalton is one  Elizabeth Shakman Hurd and Nadia Marzouki in Boston Review:

Elizabeth Shakman Hurd and Nadia Marzouki in Boston Review: Hannah Levintova in Mother Jones:

Hannah Levintova in Mother Jones: Maya Adereth interviews Felipe González in Phenomenal World:

Maya Adereth interviews Felipe González in Phenomenal World: Sam Moyn in The New Republic:

Sam Moyn in The New Republic: In spring thoughts traditionally turn to travelling, and so to

In spring thoughts traditionally turn to travelling, and so to  For generations, Anna Karenina and Emma Bovary have loomed as the nonpareils of self-loathing literary heroines. For Anna, guilt over having abandoned her husband and child, paired with a jealous nature, compels her to destroy the love she shares with Count Vronsky — and head for the train tracks. For Emma, dumped by a conscience-free bachelor with whom she has an extramarital affair — and unable to repay the debts she accrues on account of her shopping addiction — a spoonful of arsenic ultimately beckons. Lately, however, Tolstoy and Flaubert have had stiff competition on the self-harm front, thanks to women novelists intent on exploring their female characters’ propensity to act out their unhappiness on their bodies.

For generations, Anna Karenina and Emma Bovary have loomed as the nonpareils of self-loathing literary heroines. For Anna, guilt over having abandoned her husband and child, paired with a jealous nature, compels her to destroy the love she shares with Count Vronsky — and head for the train tracks. For Emma, dumped by a conscience-free bachelor with whom she has an extramarital affair — and unable to repay the debts she accrues on account of her shopping addiction — a spoonful of arsenic ultimately beckons. Lately, however, Tolstoy and Flaubert have had stiff competition on the self-harm front, thanks to women novelists intent on exploring their female characters’ propensity to act out their unhappiness on their bodies.