by David Oates

A missing tradition is haunting us, though we may not even realize it’s missing. It was called “conservatism,” and in the Anglo-American political tradition it has a record of partnering with liberals to create some of our greatest moments of democratic progress.

Our new president did once publicly hope to govern under a new and restored regime of that legendary chimera “bipartisanship,” liberals and conservatives hammering out compromise bills that advance the public interest. But that fantasy has quickly faded. Even after the departure of the former president and his hateful ways, what’s left of the Republican party seems to be a beast of unqualified partisanship, angry, ravenous, utterly uncompromising.

This became obvious when the “Covid Relief Bill” had to be passed in the Senate with only Democratic votes. Yet it was almost self-evidently needed as a response to an unprecedented public crisis. It was beneficial enough for some Republicans to take credit for it in public . . . despite having voted against it.

Where is the GOP that is heir to, for instance, the conservatives who helped pass civil rights legislation and who founded the Environmental Protection Agency? Or heir to the British conservatives (Tories) who expanded the electorate and made the entire system broader, less class-based, more democratic? Plaintively we ask, where are the conservatives of old? Ay, where are they?

Replaced by reactionaries, every one. And this is not name-calling. It’s sober truth. The United States, as of this writing, has no conservative party. Probably hasn’t for a decade or more.

The grand Anglo-American tradition of careful conservatives offering measured reform and real progress has vanished from America. An apocalyptic trio has replaced them: resentment, revanchism, and reaction. With three “R’s,” alliterative, as if for a tidy little sermon. And I can’t help wondering: what is the sickness of soul that leads to such angry irrationality? Read more »

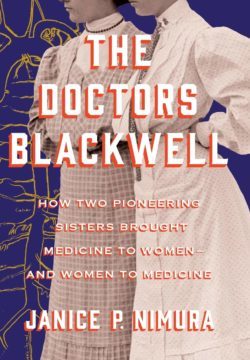

Over recent times, many books have been published with the aim of writing women into history and crediting them for the achievements they have made to the benefit of humanity more broadly. Janice P. Nimura’s The Doctors Blackwell is in that genre of women’s history and she effectively narrates the biographies of the first two remarkable women to study and practice medicine in the United States: Elizabeth Blackwell and her younger sister, Emily.

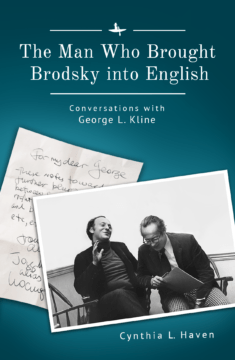

Over recent times, many books have been published with the aim of writing women into history and crediting them for the achievements they have made to the benefit of humanity more broadly. Janice P. Nimura’s The Doctors Blackwell is in that genre of women’s history and she effectively narrates the biographies of the first two remarkable women to study and practice medicine in the United States: Elizabeth Blackwell and her younger sister, Emily. Cynthia, let me begin by asking you to describe your path to the book—a double path that led you to Joseph Brodsky and to George L. Kline.

Cynthia, let me begin by asking you to describe your path to the book—a double path that led you to Joseph Brodsky and to George L. Kline.

When you think about what separates humans from chimpanzees and other apes, you might think of our big brains, or the fact that we get around on two legs rather than four. But we have another distinguishing feature: water efficiency.

When you think about what separates humans from chimpanzees and other apes, you might think of our big brains, or the fact that we get around on two legs rather than four. But we have another distinguishing feature: water efficiency. Mathematician Alexander Grothendieck was born in 1928 to anarchist parents who left him to spend the majority of his formative years with foster parents. His father was murdered in Auschwitz. As his mother was detained, he grew up stateless, hiding from the Gestapo in occupied France. All the while, he taught himself mathematics from books and before his twentieth birthday had re-discovered for himself a proof of the

Mathematician Alexander Grothendieck was born in 1928 to anarchist parents who left him to spend the majority of his formative years with foster parents. His father was murdered in Auschwitz. As his mother was detained, he grew up stateless, hiding from the Gestapo in occupied France. All the while, he taught himself mathematics from books and before his twentieth birthday had re-discovered for himself a proof of the  Claudia Sahm over at INET:

Claudia Sahm over at INET: Now an academic classic, Orientalism was at first an unlikely best seller. Begun just as the Watergate hearings were nearing their end and published in 1978, it opens with a stark cameo of the gutted buildings of civil-war Beirut. Then, in a few paragraphs, readers are whisked off to the history of an obscure academic discipline from the Romantic era. Chapters jump from 19th-century fiction to the opéra bouffe of the American news cycle and the sordid doings of Henry Kissinger. Unless one had already been reading Edward Said or was familiar with the writings of the historian William Appleman Williams on empire “as a way of life” or the poetry of Lamartine, the choice of source materials might seem confusing or overwhelming. And so it did to the linguists and historians who fumed over the book’s success. For half of its readers, the book was a triumph, for the other half a scandal, but no one could ignore it.

Now an academic classic, Orientalism was at first an unlikely best seller. Begun just as the Watergate hearings were nearing their end and published in 1978, it opens with a stark cameo of the gutted buildings of civil-war Beirut. Then, in a few paragraphs, readers are whisked off to the history of an obscure academic discipline from the Romantic era. Chapters jump from 19th-century fiction to the opéra bouffe of the American news cycle and the sordid doings of Henry Kissinger. Unless one had already been reading Edward Said or was familiar with the writings of the historian William Appleman Williams on empire “as a way of life” or the poetry of Lamartine, the choice of source materials might seem confusing or overwhelming. And so it did to the linguists and historians who fumed over the book’s success. For half of its readers, the book was a triumph, for the other half a scandal, but no one could ignore it.

James Meadway in OpenDemocracy:

James Meadway in OpenDemocracy: Thomas Moynihan in Aeon:

Thomas Moynihan in Aeon: Alexander Zevin in New Left Review:

Alexander Zevin in New Left Review: