Safina Nabi in The Christian Science Monitor:

After climbing a stiff wooden stair, we reach the “Traveler’s Library,” its walls painted white and windows open on three sides. The front overlooks Dal Lake’s houseboats and other boats for everyday use. Next to an old green sofa is a woven wicker table. And on the right are Mr. Oata’s books. With about 600 volumes, this library may not look like much. But for years, this room has been a place where Kashmir – a beautiful but long fought-over Muslim-majority region, tucked at the top of India – has touched the wider world. It’s been an oasis for visitors, and readers; but most of all, for one book-lover who can’t read. “Ask as many questions as you can to get the information you require,” Mrs. Oata says, before her husband comes in. “He will not explain things on his own.” She laughs and leaves the room.

After climbing a stiff wooden stair, we reach the “Traveler’s Library,” its walls painted white and windows open on three sides. The front overlooks Dal Lake’s houseboats and other boats for everyday use. Next to an old green sofa is a woven wicker table. And on the right are Mr. Oata’s books. With about 600 volumes, this library may not look like much. But for years, this room has been a place where Kashmir – a beautiful but long fought-over Muslim-majority region, tucked at the top of India – has touched the wider world. It’s been an oasis for visitors, and readers; but most of all, for one book-lover who can’t read. “Ask as many questions as you can to get the information you require,” Mrs. Oata says, before her husband comes in. “He will not explain things on his own.” She laughs and leaves the room.

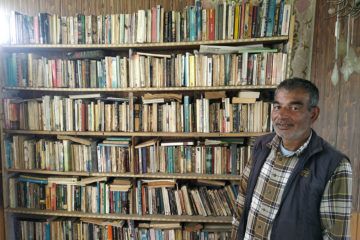

As Mr. Oata, dressed in a warm shirt and vest, walks me through his library I scan the names on the shelves. “Only Time Will Tell” and “The Sins of the Father,” by English novelist Jeffrey Archer. Next to them is Paulo Coelho, from Brazil. There are books by Jane Austen, Dan Brown, and Majgull Axelsson, a Swedish journalist. He speaks hesitantly, in a soft voice. But once he starts chatting about books, his voice overflows with enthusiasm.

Born in Kashmir, the eldest son of a plumber and a housewife, he left home at 16 in search of work to support his family. He moved across India, from one tourist destination to the next, selling Kashmiri arts and crafts. He still regrets not completing his formal education. Now and then, he noticed tourists at his stall holding books. One day, a man handed one to Mr. Oata, who asked him to summarize its contents. From then on, he asked book browsers if they’d be willing to swap, and tell him what the story was about – “and they would do it happily.” Over the years, he moved to India’s southeast, then west to Karnataka, selling jewelry, shawls, rugs, and hand-embroidered bags. Over time, he collected hundreds of books, mostly by international authors, and created his first small library. But he yearned to come back to the Kashmir Valley. So after much deliberation, he packed his books and went home in 2007. “I feel writers are always alive forever through their books, even after death, and for me that is such an interesting aspect,” Mr. Oata says, adding that his books are his “most precious possession.” “Though I cannot read, I can remember most of the books: their theme, the name of the author, and the country that the author belonged to,” he says. “I have remembered it all by remembering the color of the book, its cover page, and symbols.”

More here.