Cristina Rivera Garza in The Paris Review:

On September 14, 2011, we awoke once again to the image of two bodies hanging from a bridge. One man, one woman. He, tied by the hands. She, by the wrists and ankles. Just like so many other similar occurrences, and as noted in newspaper articles with a certain amount of trepidation, the bodies showed signs of having been tortured. Entrails erupted from the woman’s abdomen, opened in three different places.

On September 14, 2011, we awoke once again to the image of two bodies hanging from a bridge. One man, one woman. He, tied by the hands. She, by the wrists and ankles. Just like so many other similar occurrences, and as noted in newspaper articles with a certain amount of trepidation, the bodies showed signs of having been tortured. Entrails erupted from the woman’s abdomen, opened in three different places.

It is difficult, of course, to write about these things. In fact, the very reason acts like these are carried out is so that they render us speechless. Their ultimate objective is to use horror to paralyze completely—an offense committed not only against human life but also, above all, against the human condition.

In Horrorism: Naming Contemporary Violence—an indispensable book for thinking through this reality, as understanding it is almost impossible—Adriana Cavarero reminds us that terror manifests when the body trembles and flees in order to survive. The terrorized body experiences fear and, upon finding itself within fear’s grasp, attempts to escape it. Meanwhile, horror, taken from the Latin verb horrere, goes far beyond the fear that so frequently alerts us to danger or threatens to transcend it. Confronted with Medusa’s decapitated head, a body destroyed beyond human recognition, the horrified part their lips and, incapable of uttering a single word, incapable of articulating the disarticulation that fills their gaze, mouth wordlessly. Horror is intrinsically linked to repugnance, Cavarero argues. Bewildered and immobile, the horrified are stripped of their agency, frozen in a scene of everlasting marble statues. They stare, and even though they stare fixedly, or perhaps precisely because they stare fixedly, they cannot do anything. More than vulnerable—a condition we all experience—they are defenseless. More than fragile, they are helpless. As such, horror is, above all, a spectacle—the most extreme spectacle of power.

More here.

The hallmarks of the Buddy Bolden myth go something like this: in the whispery pre-jazz world of turn of the twentieth century New Orleans, one titanic musical presence loomed larger than any – Bolden, the Paul Bunyan of the cornet. He played louder, harder, and hotter than any horn player before, or since. Unlike the ensembles led by his contemporaries, most or all of whom read printed sheet music on the bandstand, Bolden’s band was primarily made up of “ear” players. They were among the first (some claim the first) to bring the art of improvisation to the kinds of ensembles that preceded the advent of the musical style we now call jazz – mostly string bands and small orchestras performing marches, hymns, rags, and popular songs of the day. No recordings of Bolden and his band exist, though an unverified story persists that he made at least one Edison wax cylinder that has never been found – the Holy Grail of early jazz. But the legend that’s been handed down is that Bolden’s playing and his ability to read and draw from the energy of his adoring, excitable audiences was radical, incendiary, and transgressive.

The hallmarks of the Buddy Bolden myth go something like this: in the whispery pre-jazz world of turn of the twentieth century New Orleans, one titanic musical presence loomed larger than any – Bolden, the Paul Bunyan of the cornet. He played louder, harder, and hotter than any horn player before, or since. Unlike the ensembles led by his contemporaries, most or all of whom read printed sheet music on the bandstand, Bolden’s band was primarily made up of “ear” players. They were among the first (some claim the first) to bring the art of improvisation to the kinds of ensembles that preceded the advent of the musical style we now call jazz – mostly string bands and small orchestras performing marches, hymns, rags, and popular songs of the day. No recordings of Bolden and his band exist, though an unverified story persists that he made at least one Edison wax cylinder that has never been found – the Holy Grail of early jazz. But the legend that’s been handed down is that Bolden’s playing and his ability to read and draw from the energy of his adoring, excitable audiences was radical, incendiary, and transgressive. The story of freemasonry is not all fraternal handshakes and matey slaps on the back, of course. Secrecy may be seductive, but it can also provoke wild speculation of a kind that didn’t end with the Portuguese Inquisition. Amid the violent upheavals of the French Revolution, the displaced Catholic priest Augustin Barruel could be heard denouncing revolutionary events as the consequence of a mischievous plot hatched by the brotherhood. Barruel provided little evidence for his claims, largely because there was none. But he did offer in his spectacularly successful book on the subject a template of supposed masonic machinations that has been recycled ever since. Dickie devotes some of his best chapters to this dark history of suspicion and persecution, with freemasons serving as scapegoats for Mussolini, Hitler and Franco, among many others. And today, freemasonry is banned everywhere in the Muslim world except Lebanon and Morocco.

The story of freemasonry is not all fraternal handshakes and matey slaps on the back, of course. Secrecy may be seductive, but it can also provoke wild speculation of a kind that didn’t end with the Portuguese Inquisition. Amid the violent upheavals of the French Revolution, the displaced Catholic priest Augustin Barruel could be heard denouncing revolutionary events as the consequence of a mischievous plot hatched by the brotherhood. Barruel provided little evidence for his claims, largely because there was none. But he did offer in his spectacularly successful book on the subject a template of supposed masonic machinations that has been recycled ever since. Dickie devotes some of his best chapters to this dark history of suspicion and persecution, with freemasons serving as scapegoats for Mussolini, Hitler and Franco, among many others. And today, freemasonry is banned everywhere in the Muslim world except Lebanon and Morocco. Today in the United States is Indigenous Peoples’ Day, a time to bear witness and remember the savagery of Christopher Columbus and other European explorers when they first encountered indigenous peoples throughout the Americas. It’s also a day to recognize and celebrate the courage, knowledges, and cultures of indigenous peoples throughout the world. It coincides with Columbus Day, a national holiday that triggers a day of protests and celebratory parades, rekindles debates about removing statues of Christopher Columbus from parks, squares and circles throughout the United States, and provokes critical discussions about the kind of stories we should be teaching the Nation’s children about his earliest encounters with indigenous communities.

Today in the United States is Indigenous Peoples’ Day, a time to bear witness and remember the savagery of Christopher Columbus and other European explorers when they first encountered indigenous peoples throughout the Americas. It’s also a day to recognize and celebrate the courage, knowledges, and cultures of indigenous peoples throughout the world. It coincides with Columbus Day, a national holiday that triggers a day of protests and celebratory parades, rekindles debates about removing statues of Christopher Columbus from parks, squares and circles throughout the United States, and provokes critical discussions about the kind of stories we should be teaching the Nation’s children about his earliest encounters with indigenous communities. Although American history curriculum has always been a site of ideological struggle, historians, history teachers, and curriculum designers have done a good job over the past several decades to revise many historical inaccuracies, distortions, and lies that helped whitewash the historical record in the service of white, male, imperialistic, and neoliberal interests. But with Trump’s latest decree to create a “1776 Commission” charged to design a “pro-American” curriculum of American history coupled with his promise to defund schools that use the 1619 Project as well as other curricular platforms that bring attention to historical facts and truths that counter the “official” curriculum, the Nation’s collective historical memory is under siege with public schools at the center of the assault. Whether Trump and the GOP actually care about how American history is represented and taught in schools or whether they are just cynically using the issue to create a political wedge between people who may otherwise be allied to vote against Trump in November is irrelevant.

Although American history curriculum has always been a site of ideological struggle, historians, history teachers, and curriculum designers have done a good job over the past several decades to revise many historical inaccuracies, distortions, and lies that helped whitewash the historical record in the service of white, male, imperialistic, and neoliberal interests. But with Trump’s latest decree to create a “1776 Commission” charged to design a “pro-American” curriculum of American history coupled with his promise to defund schools that use the 1619 Project as well as other curricular platforms that bring attention to historical facts and truths that counter the “official” curriculum, the Nation’s collective historical memory is under siege with public schools at the center of the assault. Whether Trump and the GOP actually care about how American history is represented and taught in schools or whether they are just cynically using the issue to create a political wedge between people who may otherwise be allied to vote against Trump in November is irrelevant.  Tabea Bakeua lives in Kiribati, a North Pacific atoll nation. Her country is likely to be the first to disappear completely under the rising seas within a few decades. Asked by foreign documentary filmmakers if she “believes” in climate change, Bakeua considers and tells them, “I have seen climate change, the consequences of climate change. But I don’t believe it as a religious person. There’s a thing in the Bible, where they say that god sends this person to tell all the people that there will be no more floods. So I am still believing in that.” She smiles, self-consciously, as she continues. “And the reason why I am still believing in that is because I’m afraid. And I don’t know how to get all my fifty or sixty family members away from here.” She’s still smiling as tears fill her eyes. “That’s why I’m afraid. But I’m putting it behind me because I just don’t know what to do.” She turns, apologetically, to wipe away her tears. [from “

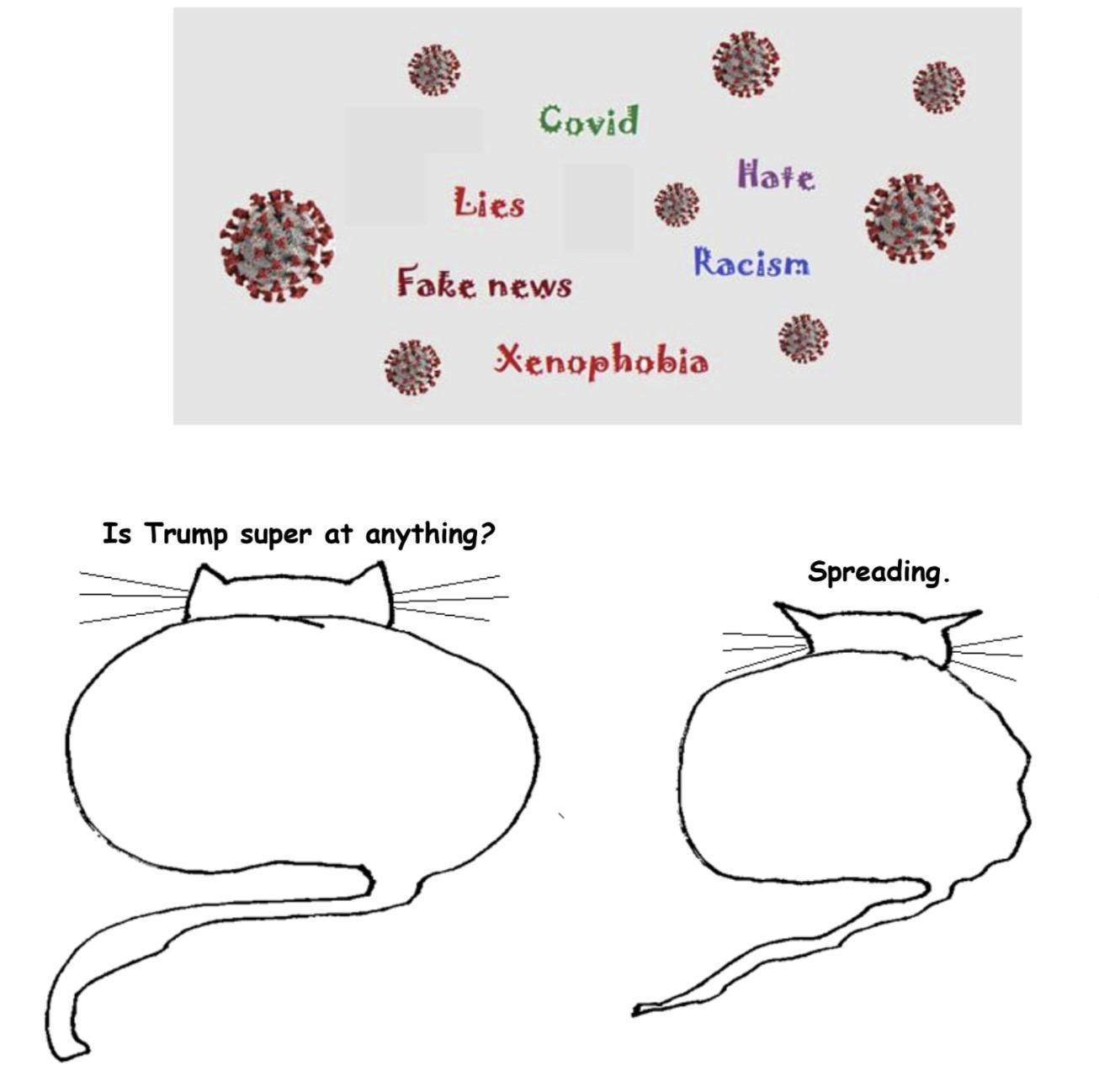

Tabea Bakeua lives in Kiribati, a North Pacific atoll nation. Her country is likely to be the first to disappear completely under the rising seas within a few decades. Asked by foreign documentary filmmakers if she “believes” in climate change, Bakeua considers and tells them, “I have seen climate change, the consequences of climate change. But I don’t believe it as a religious person. There’s a thing in the Bible, where they say that god sends this person to tell all the people that there will be no more floods. So I am still believing in that.” She smiles, self-consciously, as she continues. “And the reason why I am still believing in that is because I’m afraid. And I don’t know how to get all my fifty or sixty family members away from here.” She’s still smiling as tears fill her eyes. “That’s why I’m afraid. But I’m putting it behind me because I just don’t know what to do.” She turns, apologetically, to wipe away her tears. [from “ We live in The Year Of Overlapping Catastrophes. Oh 2020, we know ye all too well. The pandemic, our very own plague. Economic depression. A quasi-fascistic con man at the head of government. The discovery that perhaps forty percent of our fellow Americans are truth-hating dupes and low-information racists. (Brits too. Decline of the Anglophone empire?)

We live in The Year Of Overlapping Catastrophes. Oh 2020, we know ye all too well. The pandemic, our very own plague. Economic depression. A quasi-fascistic con man at the head of government. The discovery that perhaps forty percent of our fellow Americans are truth-hating dupes and low-information racists. (Brits too. Decline of the Anglophone empire?)

There are times where we are simply unable to surpass our elders.

There are times where we are simply unable to surpass our elders.

A system update recently downloaded to my cellphone included artificial intelligence capable of facial recognition. I know this because, when I subsequently opened the “Gallery” function to send a photograph, I discovered that the refurbished app had taken it upon itself to create a new “album” (alongside “Camera”, “Downloads” and “Screenshots”) called “Stories”, within which I found assemblages of my own pictures, culled from all of those other albums and assorted thematically, evidently because they depicted identical, or similar, figures.

A system update recently downloaded to my cellphone included artificial intelligence capable of facial recognition. I know this because, when I subsequently opened the “Gallery” function to send a photograph, I discovered that the refurbished app had taken it upon itself to create a new “album” (alongside “Camera”, “Downloads” and “Screenshots”) called “Stories”, within which I found assemblages of my own pictures, culled from all of those other albums and assorted thematically, evidently because they depicted identical, or similar, figures. FRONT PORCH

FRONT PORCH

Is there anything more clichéd than some spoiled, petulant celebrity publicly threatening to move to Canada if the candidate they most despise wins an election? These tantrums have at least four problems:

Is there anything more clichéd than some spoiled, petulant celebrity publicly threatening to move to Canada if the candidate they most despise wins an election? These tantrums have at least four problems:

Last time, in

Last time, in