Francis Fukuyama in American Purpose:

The “democracy” under attack today is a shorthand for liberal democracy, and what is really under greatest threat is the liberal component of this pair. The democracy part refers to the accountability of those who hold political power through mechanisms like free and fair multiparty elections under universal adult franchise. The liberal part, by contrast, refers primarily to a rule of law that constrains the power of government and requires that even the most powerful actors in the system operate under the same general rules as ordinary citizens. Liberal democracies, in other words, have a constitutional system of checks and balances that limits the power of elected leaders.

The “democracy” under attack today is a shorthand for liberal democracy, and what is really under greatest threat is the liberal component of this pair. The democracy part refers to the accountability of those who hold political power through mechanisms like free and fair multiparty elections under universal adult franchise. The liberal part, by contrast, refers primarily to a rule of law that constrains the power of government and requires that even the most powerful actors in the system operate under the same general rules as ordinary citizens. Liberal democracies, in other words, have a constitutional system of checks and balances that limits the power of elected leaders.

Democracy itself is being challenged by authoritarian states like Russia and China that manipulate or dispense with free and fair elections. But the more insidious threat arises from populists within existing liberal democracies who are using the legitimacy they gain through their electoral mandates to challenge or undermine liberal institutions.

More here.

The

The

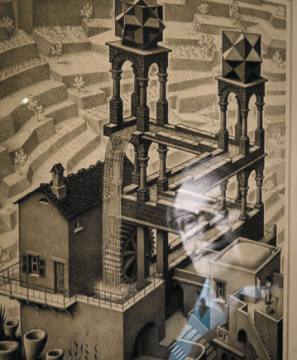

Penrose hails from one of the great intellectual dynasties of the 20th century. His father Lionel was a distinguished psychiatrist and geneticist, his uncle was the surrealist artist Roland Penrose. Roger was one of four children; older brother Oliver became a theoretical physicist, younger brother Jonathan was British chess champion a record-breaking 10 times, and sister Shirley Hodgson is a professor of cancer genetics.

Penrose hails from one of the great intellectual dynasties of the 20th century. His father Lionel was a distinguished psychiatrist and geneticist, his uncle was the surrealist artist Roland Penrose. Roger was one of four children; older brother Oliver became a theoretical physicist, younger brother Jonathan was British chess champion a record-breaking 10 times, and sister Shirley Hodgson is a professor of cancer genetics. According to copies of copies of fragments of ancient texts, Pythagoras in about 500 B.C. exhorted his followers: Don’t eat beans! Why he issued this prohibition is anybody’s guess (Aristotle thought he knew), but it doesn’t much matter because the idea never caught on. According to Joseph Henrich, some unknown early church fathers about a thousand years later promulgated the edict: Don’t marry your cousin! Why they did this is also unclear, but if Henrich is right — and he develops a fascinating case brimming with evidence — this prohibition changed the face of the world, by eventually creating societies and people that were WEIRD: Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic. In the argument put forward in this engagingly written, excellently organized and meticulously argued book, this simple rule triggered a cascade of changes, creating states to replace tribes, science to replace lore and law to replace custom. If you are reading this you are very probably WEIRD, and so are almost all of your friends and associates, but we are outliers on many psychological measures.

According to copies of copies of fragments of ancient texts, Pythagoras in about 500 B.C. exhorted his followers: Don’t eat beans! Why he issued this prohibition is anybody’s guess (Aristotle thought he knew), but it doesn’t much matter because the idea never caught on. According to Joseph Henrich, some unknown early church fathers about a thousand years later promulgated the edict: Don’t marry your cousin! Why they did this is also unclear, but if Henrich is right — and he develops a fascinating case brimming with evidence — this prohibition changed the face of the world, by eventually creating societies and people that were WEIRD: Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic. In the argument put forward in this engagingly written, excellently organized and meticulously argued book, this simple rule triggered a cascade of changes, creating states to replace tribes, science to replace lore and law to replace custom. If you are reading this you are very probably WEIRD, and so are almost all of your friends and associates, but we are outliers on many psychological measures.

Jonathan Hopkin in Aeon:

Jonathan Hopkin in Aeon: Julian Baggini makes the case in Prospect:

Julian Baggini makes the case in Prospect: Neil Fligstein and Steven Vogel in Boston Review:

Neil Fligstein and Steven Vogel in Boston Review: America meant all sorts of things to Lawrence, many of them adumbrated in his Studies in Classic American Literature (1923). In The Bad Side of Books, there’s an essay called “Pan in America” (1924), which starts from the cry that echoed around the Mediterranean as paganism faded: “The Great God Pan is dead!” What that meant, according to Lawrence, was that the possibility of life lived in spontaneous unison with nature dwindled as commerce, technology, and metaphysical religion advanced. Pan seemed still alive to Lawrence in the Indians of the Southwest, and he conjured a graphic account of the animist mind and imagination. But even there, Pan was “dying fast”; every Indian, Lawrence thought, “will kill Pan with his own hands for the sake of a motor car.” Who, given the choice the essay poses—“to live among the living, or to run on wheels”—would choose what Lawrence called “life”? Pretty much no one, he thought, though he returned to this opposition again and again.

America meant all sorts of things to Lawrence, many of them adumbrated in his Studies in Classic American Literature (1923). In The Bad Side of Books, there’s an essay called “Pan in America” (1924), which starts from the cry that echoed around the Mediterranean as paganism faded: “The Great God Pan is dead!” What that meant, according to Lawrence, was that the possibility of life lived in spontaneous unison with nature dwindled as commerce, technology, and metaphysical religion advanced. Pan seemed still alive to Lawrence in the Indians of the Southwest, and he conjured a graphic account of the animist mind and imagination. But even there, Pan was “dying fast”; every Indian, Lawrence thought, “will kill Pan with his own hands for the sake of a motor car.” Who, given the choice the essay poses—“to live among the living, or to run on wheels”—would choose what Lawrence called “life”? Pretty much no one, he thought, though he returned to this opposition again and again. Somewhere within the storerooms of London’s staid, gray-faced Tate Gallery (for it’s currently no longer on exhibit) is an 1834 painting by J.M.W. Turner entitled “The Golden Bough.” Rendered in that painter’s characteristic sfumato of smeared light and smoky color, Turner’s composition depicts a scene from Virgil’s epic

Somewhere within the storerooms of London’s staid, gray-faced Tate Gallery (for it’s currently no longer on exhibit) is an 1834 painting by J.M.W. Turner entitled “The Golden Bough.” Rendered in that painter’s characteristic sfumato of smeared light and smoky color, Turner’s composition depicts a scene from Virgil’s epic  The election is 25 days away, and President Donald Trump’s political prognosis is not good. He’s

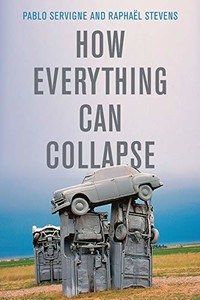

The election is 25 days away, and President Donald Trump’s political prognosis is not good. He’s  “UTOPIA HAS SUDDENLY changed camp,” write Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens in How Everything Can Collapse: A Manual for Our Times, just out in an English translation by Andrew Brown. “Today, the utopian is whoever believes that everything can just keep going as before.” In 2015, when the book was first published in France, such a statement might have sounded alarmist. In 2020, Collapse feels positively prophetic. Things have not kept going as before, and it seems increasingly doubtful that they ever will again.

“UTOPIA HAS SUDDENLY changed camp,” write Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens in How Everything Can Collapse: A Manual for Our Times, just out in an English translation by Andrew Brown. “Today, the utopian is whoever believes that everything can just keep going as before.” In 2015, when the book was first published in France, such a statement might have sounded alarmist. In 2020, Collapse feels positively prophetic. Things have not kept going as before, and it seems increasingly doubtful that they ever will again.