by Raji Jayaraman

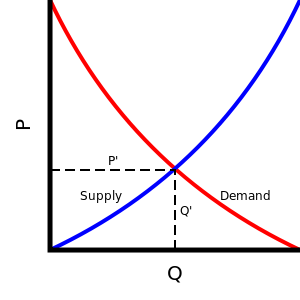

Every Econ 101 student learns the basic model of demand and supply. It’s pretty straight forward. Picture a graph with the price of a product or service on the vertical axis and the quantity supplied and demanded on the horizontal axis. There are two curves drawn on this graph: the demand curve and the supply curve. The demand curve is downward sloping because as prices decrease, consumers are willing to buy more. The supply curve is upward sloping because producers are willing to supply more when they are paid more. The “competitive equilibrium price” of the product or service is where supply equals demand: two curves intersect. When prices are higher than the equilibrium price, supply is greater than demand: there is “excess supply”. This makes sense: at higher prices, suppliers are going to be happy to sell more, but consumers aren’t willing to buy as much.

Every Econ 101 student learns the basic model of demand and supply. It’s pretty straight forward. Picture a graph with the price of a product or service on the vertical axis and the quantity supplied and demanded on the horizontal axis. There are two curves drawn on this graph: the demand curve and the supply curve. The demand curve is downward sloping because as prices decrease, consumers are willing to buy more. The supply curve is upward sloping because producers are willing to supply more when they are paid more. The “competitive equilibrium price” of the product or service is where supply equals demand: two curves intersect. When prices are higher than the equilibrium price, supply is greater than demand: there is “excess supply”. This makes sense: at higher prices, suppliers are going to be happy to sell more, but consumers aren’t willing to buy as much.

Economic conservatives often apply this logic to justify their opposition to a minimum wage. The argument goes like this. Minimum wages mandate that the price of labour be set above the market wage. At the new, higher wage there are more people willing to work and fewer jobs to go around because hiring a worker is now more costly to employers. In other words, there will be an excess supply of labour. Another way of saying this is that there’s going to be more (involuntary) unemployment.

Now, of course there are many excellent reasons to want to raise the minimum wage, none which have anything to do with economics. Trying to ensure that low-wage workers are paid decently is important if you care about things like equity, human decency, and fairness. But if my support for minimum wages rested on my commitment to social justice, the prospect of this policy instrument causing a dramatic increase in unemployment would give me pause. It’s hard to maintain the moral higher ground when my favoured policy improves the wages of those who are lucky enough to have a job but drives countless others into unemployment.

The good news is that a large body of economic research from rich countries indicates that, for the most part, unemployment hasn’t increased dramatically with the introduction of higher minimum wages. Part of this may be because the minimum wage increases have tended to be modest; you don’t have to be arch conservative or have great economic insight to anticipate that a massive minimum wage hike may increase unemployment. But a more important reason is that in a lot of places, employers get to dictate the wage rate. They may have this power because workers are reluctant to switch jobs…because their kids go to the local school and aging parents live next door. As a result, employers can get away with paying their workers less than they are worth to the company, without worrying that they’ll quit for a job elsewhere. It may also be that there are only a handful of major employers in an area, like an Amazon warehouse or a local Walmart, in which case employers can once again get away with paying low wages workers a pittance because, really, what other option do these workers have?

In both cases, employers don’t just pay employees the going wage rate. Since they have market power, they set that wage. The fact that employers are not price takers in many local labour markets, means that the simple model of demand and supply, though useful in understanding many other markets, does not apply in these particular settings. In other words, dire predictions of rampant unemployment arising from minimum wages are often off the mark because doomsayers have deployed the wrong model of labour markets.

Why do they use the wrong model? Any number of reasons. Maybe it’s accidental. Demand-supply is after all a workhorse model for predictions in economics, and works very well in understanding all sorts of other markets. Maybe it’s deliberate. Maybe all they care about is corporate profits; higher wages mean higher costs and lower profits, and this model gives them a champion-of-the-working-class rationale to oppose higher wages.

Or maybe the problem is that they never learned that a key assumption in the demand and supply model is that there is a large number of buyers and sellers who take prices as given. Applied to the labour markets, the demand-supply model requires that there be a large number of employers and workers who take wages as given.

Market power is dangerous, and failing to understand this can have dire consequences. Generic opposition to minimum wages is only one consequential example. There are many others. We laud the benefits of capitalism in spurring innovation, but then encourage IP-protected vaccine monopolies. This undermines market efficiency. Vaccines don’t reach large parts of the world, variants are brewed, and the pandemic continues unabated. Facebook dominants social media, where its manipulative algorithms eat away at everything, from our mental health to our democracies. Amazon rules the retail market while mom and pop’s stores, which house the souls of local communities, go bust.

There are, of course, institutions whose job it is to hold companies’ market power in check–places like the European Commission and the Federal Trade Commission. But they don’t seem to be doing a bang up job. We would all be so much better off if those that advocate so passionately for unfettered markets understood that the beauty of markets rests on slaying the beast of market power. I wish they had paid attention in Econ 101. I wish we had done a better job getting them to pay attention.