by Andrea Scrima

1.

What is power? The answer is relative, contingent on context. We speak of the power of sexual allure, the power of persuasion, of charisma, but these only rarely translate into sustainable structures of actual dominance. In a capitalist democracy, power is generally economic and political; it’s less frequently defined as intellectual or moral force. As an artist and writer whose works are not, as sometimes happens in other political systems, banned (which would enhance their power in a different intellectual economy), but merely sell poorly, I have relatively little power, and so my words come from the position of a person frequently, in one way or another, subject to the will of others.

Given the vast difference in agency prevailing between artists and patrons, is an intellectual, artistic, ethical discussion on equal terms even possible? Wealth inspires conflicting emotions in people who don’t have it: envy for the ease and security it affords, because so many of the problems that plague us can be solved with money; frustration that the notion of equitable taxation is evidently a utopian impossibility; dismay at the injustices of wealth distribution and the damage the ever-widening economic divide between the haves and have-nots has inflicted on society, the environment, and world peace. But without wealth, it’s said, we would never have had the splendor of kingdoms and courts; the magnificent cathedrals and palaces would never have been built, the arts would never have flourished. The concentration of wealth and the judicious application of its power is what makes civilizations thrive. Indeed, people working in the arts will always find themselves in happy or unhappy alliance with those in a position to fund their endeavors and will forever speculate on the underlying motivations of those who give so “generously.” The relationship that binds the arts to wealth is inherently problematic, a form of co-dependence in which power is negotiated according to ever-shifting terms.

2.

In Rome, the fifth-century basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore houses the captivating Salus Populi Romani, the Marian icon said to have been painted by Saint Luke from life, that is, during Mary’s lifetime and in her physical presence. Throughout its nearly 1,500-year history, the icon was seen as the divine vehicle of numerous miracles. During the first months of the Covid pandemic, Pope Francis had the icon removed from its place in the Cappella Paolina and brought, together with a fourteenth-century crucifix from the church San Marcello al Corso said to have driven the plague of 1522 out of Rome, to Saint Peter’s Square for his “Urbi et Orbi” blessing. He delivered the papal address alone, in the absence of the usual crowd of worshippers, outside the empty cathedral and under the steady downpour of a depressing March rain. It was more than an ecclesiastic rite; it was also a spectacle invoking the magical powers attributed to art, and in one of humanity’s most frightening moments it inspired awe worldwide, including among the non-religious. Santa Maria Maggiore also reputedly houses the first gold mined by the enslaved in the New World, which explorers sailing under Spanish rule brought back from America and which Isabella I of the Reconquista (who was also responsible for the Alhambra Decree mandating the mass expulsion of the Jews and for unleashing the Spanish Inquisition) donated to the Vatican to eventually gild the rosettes of Santa Maria Maggiore’s sumptuous ceiling. This is one of the darker, one might say subconscious, sides to this global display of humility and reverence, and as such stands for an underlying paradox at the heart of every spectacle.

Art, we remind ourselves, always exists in close proximity to power and its inherent brutality. Oddly, a civilization’s greatness or lack thereof is often judged less by the cruelty of its social organization or economy than the degree to which it enables art to prosper. Art was once believed to express the loftiest thoughts and sentiments human beings are capable of; whatever art has come to mean today, it has retained a good deal of its cultural agency. But while the relationship between artist and patron can, on the surface, seem mutually beneficial and gratifying, it is deception and mystique that it deals in—giving rise to the trickster, the poseur, and the sycophant—, because regardless of the cultural capital art is perceived to be, and the fact that wealth is keen to associate itself with it, the inherent asymmetry in power between artist and patron precludes any possibility of a negotiation on equal terms. The artist needs to play along to survive. As long as one sticks to the script, according to which the patron is noble and the artist grateful, all is well. But the moment one steps aside and questions the terms of transaction, punishment arrives. Because the power is, and will always remain on the side of the very wealthy.

3.

Not long ago, a small group of artist members of an association I belong, or at this point belonged to, attempted to address authoritarian structures on the part of a board whose behavior we found to be in conflict with the institution’s principles. The institution is known for taking a critical stance on politically controversial themes in a highly symbolic geopolitical setting; as a German art center in Italy, its program of resident artists, exhibitions, film screenings, workshops, and lectures speaks to a larger understanding of the Mediterranean region as a common cultural historical space extending to northern Africa and the Levant. We wanted to ensure that this tradition not be phased out in favor of turning it into an elitist showcase, as most institutions of this kind sooner or later become.

The response we met with on the part of the board failed to answer to any of the concerns we’d brought up, but raised, in an inscrutable tone that alternated between solemn and ominous, the specter of terrible things to come if the trust placed in the institution by the funding bodies were “disappointed” in any way. What was at stake? There was no theft of funds, no sexual abuse, no crime committed—but a problem of non-accountability and authoritarian control that threatened to silence critical dissent and curtail artistic freedom, the very principles at the heart of the institution. What complicated the situation was the enormous wealth of one of these board members, who acts as chair. To be more precise, the person is a billionaire; further research reveals that each of the board members, in one way or another, profits or hopes to profit from the proximity to this enormous capital. Understandably, each of these persons is keen to ward off any potential dangers to their position on the board. And so as artist members of an institution founded by artists for artists, we intended to propose two candidates to the board to effectuate a more equitable representation. To our great surprise, the chairwoman reached out and invited them to her sumptuous villa for a confidential tête-à-tête, where she assured them of her unflinching support. It was a ruse; behind the scenes, the chairwoman was busy recruiting dozens of new members from her immediate family and close circle of friends to maintain a majority in a membership vote, come what may. In other words, we had been duped, lulled into thinking that we had the board’s full support and didn’t, in fact, need to remain alert and strategize.

One might point out that is hardly unusual, yet the expectations placed in arts institutions are somewhat different than those of the corporate world. The chairwoman’s wealth ensures that the people who flock to her make themselves indispensable in various ways and refer to her in flattering terms. Perhaps the admission of an outsider to this bastion of mutual interests would have meant having a witness, an observer in the inner ranks. But this realization, as is so often the case, came in retrospect. When the truth emerged, the chairwoman showed no shame or embarrassment at being caught in the act; instead, she had the serene demeanor of someone protecting her natural right. We had been deceived, because we hadn’t understood that the role we were expected to play—not as equal partners, but as grateful, compliant members content to obey, admire, and blindly trust the board’s every word—was evidently a psychic necessity for some of these individuals, or that the chairwoman’s sense of identity, importance, and self-esteem was predicated on a clearly defined hierarchy between patron and artist, with no interest in what the actual artists present had to say.

4.

When we consider that power is, by definition, the ability to use force to make one’s will prevail, to mobilize an army, militia, or the police to protect or to assist in the carrying out of one’s interests, we have to conclude that power consists in its recourse to coercion. It is inherently violent. And so it follows that because wealth is power, and also has recourse to the use of coercive force—the ability to set an attorney’s office in motion, for instance, in order to implement punitive legal or financial measures against a perceived opponent to ensure that its objectives are met—wealth is also, albeit far more discreetly, violent. The curious thing is this: wealth nonetheless seeks to equate itself with the greater good; indeed, this need to appear fundamentally noble and charitable—coupled with a belief in the veracity of this construct—can be seen as its psychopathy.

On the surface, there is always a justification for power’s brutality: the need to maintain order, to forestall a damaging disruption to the status quo, to conquer challenges to ownership, to hegemony, to an hierarchy that masquerades as stability: political, economic, or otherwise. Art, on the other hand, when not serving wealth or its own efforts to position itself in relation to this wealth, is frequently critical in nature; it calls attention to injustice, to mendacity, to hypocrisy. It follows that the relationship between the two is complicated and sometimes volatile, and indeed, art history provides abundant examples of artworks posing as a celebration of power within which the artist’s implicit criticism is camouflaged in a myriad of subtle and ingenious ways.

5.

The Cappella Sassetti in the basilica of Santa Trinita in Florence houses a series of frescoes on the life of St. Francis of Assisi, painted by Domenico Ghirlandaio and commissioned by Francesco Sassetti, who managed the banking interests of the Medici family abroad. The iconography of the ensemble is striking for several reasons, including its display of power politics in Florence of the Quattrocento. Each figure in the ensemble has designs: Lorenzo de’ Medici is seeking to maintain power and to prepare the Florentine public for the ascension of one of his sons, Giovanni, to a higher ecclesiastical position (he eventually became pope); Sassetti, still very wealthy, is hoping to rehabilitate himself both professionally and spiritually after suffering significant losses as the head of the Medici bank abroad. He’d originally intended to commemorate the life of his patron saint and the Franciscan order in his chapel at Santa Maria Novella—the plan, however, met with refusal on the part of the competing Dominicans administering the church, despite the fact that the family had long held the rights to the chapel. And so the family chapel was moved to Santa Trinita, and the frescoes of the Sassetti Chapel painted there. Ghirlandaio, already the head of a successful workshop, included his own likeness in this display of the rich and powerful; soon after completing the suite of frescoes celebrating the life of St. Francis, he was commissioned to paint the former Sassetti Chapel in the church of Santa Maria Novella, the rights to which the monks had sold to Giovanni Tornabuoni, Francesco’s bitter rival and eventual successor as bank manager. Switching alliances seamlessly, Ghirlandaio knew how to position himself in the visual economy of the time: once again, he included his own portrait and that of his brother and brother-in-law in one of the Cappella Tornabuoni panels, The Expulsion of Joachim from the Temple, thus ensuring his fame for all posterity.

Both chapels are beautifully executed works of religious iconography so intertwined with the politics of their day that to even contemplate an equivalent today defies the imagination. Because while we are fascinated by wealth and celebrity, and it’s not too much of a stretch to say that we, in the true sense of the word, worship it—it would be difficult to imagine individuals orchestrating their power today as figures in a religious display created by the best artists of our time for the purpose of veneration and prayer. Yet perhaps we are closer to this than we realize.

6.

We celebrate the great patrons of the arts for their exceptional taste and vision; they have gone down in history for enabling artists to create humanity’s most magnificent cultural achievements. But do we ask ourselves what they get in return? Perhaps it’s merely a transaction in a pleasure economy, in which one party is paying and the other providing a service; indeed, people who can afford art often imagine that it reflects their own true nature, their inner worth. But what if a mysterious transubstantiation takes place? At what point does the person funding the art become equated with the more sublime reaches of the human soul the art is said to express? And when does the person begin believing in this conflation? One only need shift one’s focus slightly to see not the beauty and splendor of humanity’s cultural triumphs, but the ruthlessness and cruelty that, almost without exception, accompany the fortunes that fund them. Yet the largely unrecorded history behind these fortunes disappears, for the most part, into obscurity. We worship wealth, fail to comprehend its psychopathy, and embrace art’s role in the rituals of this worship.

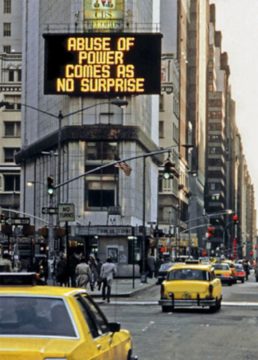

As Jenny Holzer once wrote, “the abuse of power comes as no surprise.” Organizing protest against the abuse of power is difficult and time-consuming: those who possess comparatively little power generally can’t afford to make mistakes and take great pains to gather their information and formulate their arguments clearly. The response on the part of power, however, is generally to obfuscate the facts, hurl accusations, inspire fear, invoke vague threats, and mythologize its own role in a melodramatic manner. It turns out that there is a language at work, a kind of script that repeats itself. Power, when exposed, almost always adopts the same rhetorical strategy of blatant self-contradiction: it takes on both an authoritarian voice and the voice of the morally indignant victim who has sacrificed time and money for the greater good and is shown not a single sign of appreciation. Its tone is histrionic and menacing, even while asserting its innocence; it avoids specifics and employs sweeping generalizations, while concealing the absence of any real substance to its argument behind a façade of outrage and righteousness. Veiled threats of legal action couched in opaque legal terminology; equating oneself with the overarching institution to embody a larger, impersonal authority; claims of various infractions major and minor and allusions to grave consequences; the imposition of random deadlines and penalties; appropriating the language of their opponent to strip it of its meaning—all become weapons in an asymmetric battle over what is demonstrably true, and what is fabricated. The aim here is to intimidate and defame those protesting the abuse of power, while planting a fear of reprisal and repercussion in the minds of anyone who would be foolish enough to side with them. As Gramsci explains, hegemonic dominance primarily relies on cultural hegemony, but in a “crisis of authority,” the “masks of consent” slip away to reveal the fist of force.

7.

In the case of our arts institution, we were made to feel this fist of force. At a recent meeting, two artists read a statement out loud to the new, at this point nearly homogenous white upper-class membership—in protest, most of the artists had since left the association—and were met by cries of “Liars!” by the chairwoman’s billionaire husband shouting out from the front row. Another board member accused them of spreading “fake news” and “conspiracy theories” and had the temerity of claiming they were guilty of “Trumpist tactics,” although one of the artists standing before them was a young woman of color whose work examines questions of institutional criticism. Indeed, one of the key formal elements in a recent large-scale installation of hers was a gigantic scaffolding erected inside the exhibition hall of an art institution: the persistent illusion that the metal poles and braces were not only holding up the ceiling, but supporting the great weight of the entire building, served as a potent metaphor for the absurdity of power’s pretense. In truth, we should have addressed the vast asymmetry at the very start of our attempts to have a say in the running of the organization. In the end, the rigged vote had all the appearance of being fair and democratic—because clandestine machinations are just that: orchestrated carefully in advance and in no danger of entering the official record. Yet even more striking was this: instead of the sense of shame one would expect them to feel the moment it became clear that we realized what they’d done—that they’d lied, that the lying was part of a larger strategy, and that we now saw through this—they seemed not embarrassed, but vindicated.

We’ve all, I hope, rebelled at one time or another, and have all been punished for whatever infractions we’ve committed; we’ve all internalized the script of power and experienced the range of emotions connected to defying its injustices. First and foremost: the fear of standing alone, without friends, ostracized and disgraced. Because there is a taboo around identifying and exposing power in our society; it’s felt to be vulgar, even in cases of obvious abuse. The person protesting is cast as an outsider, an anarchist, a failure. Young people are brought up to, if not respect, then at least fear authority, to acquiesce to the power of the teacher, policeman, doctor, nation state, etc. Even if a person’s rebellious nature hasn’t already been driven out of them by the time they enter the hierarchy of the workplace, it takes great courage to speak out against power, and it’s no wonder that many refrain—either out of an opportunistic instinct to hedge their bets and side with the winner, or because the risk to their livelihoods, families, or lives seems out of proportion to the cause.

As Simone Weil wrote in Oppression and Liberty, “power contains a sort of fatality which weighs as pitilessly on those who command as on those who obey.” What is the psychology of power, and is it possible to understand it as it’s unfolding? One distinct impression remains: boards of directors—even those of art institutions—operate according to rules of conduct that are intrinsic to corporate culture, but morally and ethically unacceptable to ordinary people in ordinary life. It follows that when ordinary people encounter this conduct and the smug deception that goes along with it, it takes them some time to understand even the basics of what is happening—and they are made to feel like naïve fools.

But even more disturbing was this: following the sham election, we were witness to the inevitable moment in which hiding behind the façade of benevolence was no longer necessary. Indeed, judging from their smiles of satisfaction, there seems to be a thrill in being exposed: the ultimate joy is evidently in being seen, and in seeing the dawning of this realization mirrored in the losing party’s gaze. Is it a form of liberation to finally let the mask fall and bask in the pleasure of being recognized for what one really is? The cat is out of the bag, and the shameless gaze not only holds your gaze, but forces you to look away—it’s as though you were feeling the shame they should be feeling, as though shame were a physical entity that seeks a vehicle; as though somebody had to be ashamed in their stead.

***

A related conversation from June 2022 can be found here.