by Ashutosh Jogalekar

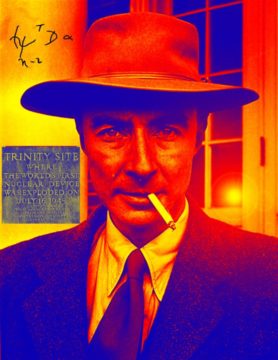

This is the first of a series of short pieces on J. Robert Oppenheimer. The others can all be found here. Popular interest in Oppenheimer’s life seems to have peaked this year with the upcoming release of Christopher Nolan’s mainstream film, “Oppenheimer”. Several books about Oppenheimer – and even a popular opera – have come out just in the last two decades. Analogies between Oppenheimer and nuclear weapons and new technologies like AI and gene editing are frequently drawn, sometimes incisively and often misleadingly. Why does this man continue to inspire so much interest? And why now?

My goal is to provide readers who might not want to read a full biography of Oppenheimer with some of the highlights of his life that address these questions and put them in context. Needless to say, this series – which is essentially chronological – is not supposed to be an exhaustive biography and is biased by what I personally think was most interesting about this brilliant, fascinating, complicated man’s life and times.

The physicist Isidor Rabi – a friend who perhaps knew Robert Oppenheimer better than he knew himself – once said that Oppenheimer was a man composed of many shining splinters. That succinct assessment captures the central dilemma of Oppenheimer’s life: identity. It was a dilemma that made him who he was and one that contributed to the myriad problems he faced in his life. I also believe that it was this dilemma that makes him a fascinating man of enduring interest, more interest than many of his contemporaries who were far better-known scientists.

To understand this dilemma it’s worth starting, as it often is, with Oppenheimer’s childhood. The affluent household where Oppenheimer was born and grew up was, in the words of a biographer, “like Ibsen’s Rosmersholm, that aristocratic estate where voices and passions were always subdued, and where children never cried – and when they grew up never laughed.”

He was born on April 22, 1904, in New York City to Julius Oppenheimer and Ella Friedman. Julius Seligmann Oppenheimer was part of the wave of German Jews who emigrated to America in the late 19th century. He followed his uncles and elder brother who had emigrated earlier and started a small business importing linings for men’s suits. Julius came to the country as a teenager, with very little means and speaking no English, but he was a man of great ambition and talent. Within just a few years he had established himself not only as a leading craftsman of his trade but as one of the city’s respectable citizens. He dressed impeccably, spoke excellent English, read voraciously in history and literature and visited New York’s famous art galleries on a regular basis.

It was probably during one of these visits that he met Ella Friedman of Baltimore, a cultured, elegant woman from a well-to-do Bavarian Jewish family who had spent a year studying the impressionists in Paris and had taught art at Barnard College. She was an accomplished painter who had an art studio of her own in the city, an unusual occupation for a woman in that era. Ella was sophisticated and socially mobile and it’s not surprising that she was impressed by the gregarious, talented and ambitious first-generation immigrant; “You have a way with you that just invites confidence in the highest degree.”, Ella wrote to Julius shortly after their meeting. The couple were married in 1903.

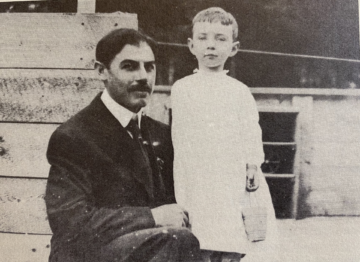

A year later their first child was born and was named Julius Robert Oppenheimer, or J. Robert Oppenheimer. Curiously, when asked later what the initial in his name stood for, Oppenheimer would say that it stood for nothing. This might have indicated a certain distance from his father, but contrary to this impression, Robert and both his parents remained close until their deaths.

Shortly after Robert’s birth, his parents moved to 155 Riverside Drive on New York’s elegant Upper West Side. With their ambitious and cultured backgrounds, it is not surprising that Julius and Ella doted on their son and tried – and could afford – to give him everything that he could want. But along with affection and instruction also came a protectiveness that did not always do Robert good. Ella in particular, while kind, was formal and guarded, and this reflected in her attitude toward her son. Her protectiveness may have arisen from a congenitally deformed hand that she hid under a white glove; it was not regarded as a subject of discussion even among close family. Four years after they had Robert the Oppenheimers had another son who died shortly after his birth. This experience made Ella seem even more distant at times.

From the beginning it was clear that Robert was a brilliant, precocious child. He devoured books, loved playing with blocks and wrote poetry. During an early trip to visit his grandfather back in Germany, he was given a set of minerals which turned him into an avid mineral collector. But all these pursuits – reading, poetry, mineralogy – were solitary ones. The loneliness of his mother after her son’s death did little to change the environment at home, Julius’s jolly German heartiness notwithstanding. And his parents’ affluence and pampering made it easy for Robert to sustain his loneliness in a protective cocoon. He was driven to school in a chauffeur-driven car and discouraged from any kind of rough-and-tumble play that is typical of young boys. Two remarks of Oppenheimer’s from his later life attest to these early influences. “I need physics more than friends”, he once confessed. And more revealingly he once remembered, with his characteristic flair for self-pity and self-irony, “I was an unctuous, repulsively good little boy. My life as a child did not prepare me for the fact that the world is full of cruel and bitter things. It gave me no normal, healthy way to be a bastard.”

Eight years after Robert was born the Oppenheimers had another son, Frank. Frank was subjected to the same affluent, protected upbringing as his elder brother, but only Robert seems to have channeled parts of the upbringing into high-brow intellectual snobbishness. Later in life, while Robert always appeared like the quintessential ivory tower intellectual, Frank was much more rough-hewn, a man of the people. Unlike Robert he was very good with his hands – he became a first-rate experimental physicist – and fluent in music; when he expressed an early interest in it, Julius characteristically hired one of America’s finest flutists to teach him, and throughout his life Frank played the instrument competently. The brothers were always close, and their letters provide some of the most penetrating insights into Robert’s thinking and personality.

During the First World War Julius’s business prospered and he became what would be today’s equivalent of a multimillionaire. With Ella he went on a whirlwind art buying tour, and soon their spacious apartment was decorated with French impressionist and van Gogh originals. A butler opened the door and a maid served tea, and friends felt an acute sense of decorum and proper behavior when visiting. If the atmosphere felt stifling, the children do not seem to have indicated so, but it was clear that only the best was expected from them.

When Robert was eight his parents enrolled him into the Ethical Culture School in New York. The school was founded by an educator and social reformer named Felix Adler whose embrace of reform Judaism and motto – deed before creed – greatly appealed to the non-observant Oppenheimers’ secular sensibilities. The school taught the value of community service and hard work as part of the essence of Jewish identity. Throughout his life Oppenheimer never practiced his religion, but Ethical Culture’s emphasis on community work and self-improvement made a deep impression on him.

At Ethical Culture he flourished. The awe that people later displayed at his intellectual fluency, speed of thinking and broad knowledge was becoming apparent at this time. His intellect had flowered in many different directions. Along with composing poetry, he read Katherine Mansfield and Dostoevsky and the Greek classics. He and a friend often stopped to inspect art at the Met. And the mineralogy hobby had turned into a serious activity; in fact, he traced his interest in physics back to his interest in properties of crystals such as birefringence. When Robert was twelve, he used the family typewriter to correspond with several well-known geologists who were members of the New York Mineralogical Society. Impressed by the contents of the correspondence, one of the members nominated Robert for membership and asked him to come visit and read a paper. The society was stunned when the learned author turned out to be a 12-year-old; a box had to be brought for young Oppenheimer to stand on and give his presentation.

By this time Robert had also acquired an unusual facility with languages, a facility that was to stay with him and impress others throughout his life. “Ask me a question in Latin”, he once told Frank as a teenager, “And I will answer in Greek.” However, while poetry, literature and languages still occupied his time, Robert’s interest in science was becoming apparent. He spent a summer doing a research project in a chemistry lab, an experience which convinced him that he wanted to become a chemist. Even later in life, when he had acquired fame as a physicist, he once said, “I loved chemistry so deeply that I automatically respond when people want to know how to interest people in science by saying, ‘Teach them elementary chemistry.’ Compared to physics it starts right in the heart of things.”

Robert’s parents’ protectiveness and its influence on him still endured; they once got a note from school asking that Robert was holding up class because he insisted on waiting for the elevator instead of taking the stairs. The sheltered upbringing was to see a rude awakening, however. One summer when Robert was fourteen, he went to a summer camp out in the woods – probably his first experience participating in independent activities with other young boys his age. He wrote his parents, saying he was in excellent spirits and was learning the “facts of life”, no doubt a reference to the bawdy humor and discussions about girls and sex that boys that age often have. Julius and Ella were alarmed and rushed to the camp; the director clamped down on the tawdry activities. When the boys at camp came to know who had told on them, they stripped Robert naked, painted his genitals green and locked him overnight in a cooler. The experience must have been humiliating and traumatic, although he does not seem to have mentioned it later and bravely endured the rest of the camp. But it was perhaps the best illustration of how fragile his life had been made by his protected childhood. He had had no healthy way to be a bastard.

Unsurprisingly Robert graduated as valedictorian of his class in early 1921. He was slotted for Harvard; then as in other times, the Ivy League school was considered a fast track to a distinguished career. But first he undertook another trip to Europe, including a mineral prospecting trip. It was during this trip that he came down with a very serious case of trench dysentery. Suddenly Harvard did not seem possible in the fall. His parents brought him home for recovering. He was so bitter about losing a year that he would lock himself in his room against his parents’ entreaties and sink deep into a chair reading Katherine Mansfield.

In desperation Julius sought the services of a sunny, warm Harvard graduate named Herbert Smith who was an English teacher at Ethical Culture. Smith was the kind of teacher who could provide both physically and mentally edifying instruction to his charges. After Robert started to recover in the spring of 1922, Smith and Julius decided that Smith should take him out West to energize his spirit. Out West meant New Mexico.

There are a handful of life events in a man’s life that in retrospect can be seen to be true turning points; in Oppenheimer’s case, that first trip to New Mexico when he was eighteen could be squarely counted as one. In that barren, austere landscape Robert flowered, his inner man freed from the restraints of home and hearth. He would emerge from the trip a confident young man ready to take on the world.

Smith took Robert to a dude ranch named Los Piños where Robert rode horses, chopped wood and learnt to brave the elements. Los Piños was in the Sangre de Cristo – the “Blood of Christ” – mountains northwest of Santa Fe. A particularly memorable aspect of the stay – a kind which Robert would cherish and repeat many times later in his life – was a packing trip through the mountain wilderness that started in the village of Frijoles, part of the Cañon de los Frijoles. Anyone who has visited these mountains (I have more than once) can attest to their stunning, expansive, primal beauty. Among the greatest natural landforms there is the Jemez Caldera, a collapsed volcanic crater twelve miles across with an enormous grassy basin inside in which herds of elk roam. Smith and Robert must have visited this caldera and ascended the valleys and peaks around it that are part of the Pajarito Plateau.

A few miles from the Jemez Caldera and the Cañon de los Frijoles, the two would have comes across a parallel canyon taking its name from the cottonwoods that dotted its valleys and mesas. Its name was Los Alamos.