by Dick Edelstein

The visit by Pope Francis to Ireland in 2018 as part of the World Meeting of Families was important since it was the first one since the historic visit by Pope John Paul II in 1979, an event that drew around one and a quarter million people to a mass in Dublin’s Phoenix Park, the biggest crowd ever seen in the country, amounting to almost one-third of the population. Since then, religious feeling in Ireland had been on the wane, along with the Church’s authority over those who considered themselves Catholics, which was in a near-fatal slump. The Church was facing an uncertain future with the number of new seminarians dropping to record lows for several years.

Still, that visit in 2018 had generated certain expectations. First, a turnout of half a million people was expected in Phoenix Park, a figure that proved to be overestimated by around 400 percent. The actual turnout—some 130,000 people—was much smaller. However, that was nothing compared to the other expectation. On account of widespread cases of sexual molestation by clergy and a generalized public dissatisfaction over the failure of the church to recognise its history of abuse and make suitable reparations to the victims, many Irish people were expecting Pope Francis, given his reputation as a liberal, to issue a detailed and lengthy apology. In recent decades, public outrage about sexual abuse by clergy had been a worldwide occurrence, but the issue had special significance in Ireland, where the moral tone of the entire country since independence had been set by the Catholic church, despite its longstanding record of abuse.

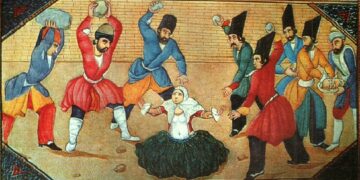

Other factors affected Irish people’s expectations of a full apology from the Pope. One of these was the Magdalene laundries scandal. Throughout much of the twentieth century, thousands of Irish women had been incarcerated in Magdalene institutions, most of which were run by Catholic religious orders. The women were forced to work without pay or benefits. Despite the outrageous violation of the women’s human rights, the Irish government colluded with their detention and was complicit in their treatment. In 2011, a group called Justice for Magdalenes made a submission to the U.N. Committee Against Torture, arguing that the Irish government’s failure to deal with the abuse amounted to continuing degrading treatment in violation of the Convention Against Torture and that the state had failed to promptly investigate “a more than 70-year system of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment of women and girls in Ireland’s Magdalene laundries”.

The story of the Magdalene Laundries was still reverberating in the public consciousness when in March 2017 Ireland was shocked by the discovery that, between 1925 and 1961, the bodies of 796 babies and young children had been interred in the grounds of the Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, County Galway, many in a septic tank. Catherine Corless, the local historian who exposed the scandal, complained to Irish legislators that nothing had been done to exhume the bodies after her research came to light despite expressions of “shock and horror” from the Government and the President. Instead, the site had been returned to its original condition. As with the Magdalene scandal, the authorities initially showed unimaginable insensitivity and cruelty towards affected families.

Thus, when Pope Francis came to visit in August 2018, Irish people expected a full and sincere apology because of his reputation for sympathy towards a number of liberal causes, his commitment to the protection of vulnerable people, and on account of a series of special circumstances in Ireland. But surprisingly, no sufficiently firm apology was forthcoming. Read more »

Sughra Raza. After The Rain. April, 2025.

Sughra Raza. After The Rain. April, 2025. Morality, according to this view, is more like taste, and in matters of taste I don’t expect others to be like me. This is of course incoherent since the very imperative to be non-judgmental is itself a moral demand, which must claim some level of objectivity since it is a rule that others are expected to follow. Judging others, according to non-judgmentalism, is something we ought not to do. It is presented as an objective moral rule.

Morality, according to this view, is more like taste, and in matters of taste I don’t expect others to be like me. This is of course incoherent since the very imperative to be non-judgmental is itself a moral demand, which must claim some level of objectivity since it is a rule that others are expected to follow. Judging others, according to non-judgmentalism, is something we ought not to do. It is presented as an objective moral rule.

On a hot summer evening in Baltimore last year, the daylight still washing over the city, I sat on my front porch, drinking a beer with a friend. Not many people passed by. Most who did were either walking a dog or making their way to the corner tavern. And then an increasingly rare sight in modern America unfolded. Two boys, perhaps ages 8 and 10, cruised past us on a bike they were sharing. The older boy stood and pedaled while the younger sat behind him.

On a hot summer evening in Baltimore last year, the daylight still washing over the city, I sat on my front porch, drinking a beer with a friend. Not many people passed by. Most who did were either walking a dog or making their way to the corner tavern. And then an increasingly rare sight in modern America unfolded. Two boys, perhaps ages 8 and 10, cruised past us on a bike they were sharing. The older boy stood and pedaled while the younger sat behind him.

If I were asked to name the creed in which I was raised, the ideology that presented itself to me in the garb of nature, I would proceed by elimination. It wasn’t Judaism, although my father’s parents were orthodox Jewish immigrants from the Czarist Pale, and we celebrated Passover with them as long as we lived in Montreal. It certainly wasn’t Christianity, despite my maternal grandparents’ birth in protestant regions of the German-speaking world; and it wasn’t the Communism Franz and Eva initially espoused in their new Canadian home, until the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact put an end to their fellow traveling in 1939. Nor can I claim our tribal allegiance to have been to psychoanalysis, my mother’s professional and personal access to secular Jewish culture, although most of my relatives have had some contact, whether fleeting or intensive, paid or paying, with psychotherapy—since the legitimate objections raised by many of them to the limits of classical Freudian theory prevent it from serving wholesale as our ancestral faith, no matter the extent to which a belief in depth psychology and the foundational importance of psychosexual development informs our discussions of family dynamics.

If I were asked to name the creed in which I was raised, the ideology that presented itself to me in the garb of nature, I would proceed by elimination. It wasn’t Judaism, although my father’s parents were orthodox Jewish immigrants from the Czarist Pale, and we celebrated Passover with them as long as we lived in Montreal. It certainly wasn’t Christianity, despite my maternal grandparents’ birth in protestant regions of the German-speaking world; and it wasn’t the Communism Franz and Eva initially espoused in their new Canadian home, until the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact put an end to their fellow traveling in 1939. Nor can I claim our tribal allegiance to have been to psychoanalysis, my mother’s professional and personal access to secular Jewish culture, although most of my relatives have had some contact, whether fleeting or intensive, paid or paying, with psychotherapy—since the legitimate objections raised by many of them to the limits of classical Freudian theory prevent it from serving wholesale as our ancestral faith, no matter the extent to which a belief in depth psychology and the foundational importance of psychosexual development informs our discussions of family dynamics. About 45 years ago, psychiatrist Irvin Yalom estimated that a good 30-50% of all cases of depression might actually be a crisis of meaninglessness, an

About 45 years ago, psychiatrist Irvin Yalom estimated that a good 30-50% of all cases of depression might actually be a crisis of meaninglessness, an