by Liam Heneghan

No one warned me that after my children finally left home when I secured the doors at night I would, in effect, be locking them out.

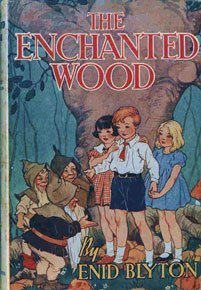

People deal with the mild trauma of being an “empty nester” in different ways, I suppose. Some handle it with quiet grace, some move cocktail hour to the early afternoon, some repurpose the bedrooms into a karaoke lounge, a discotheque and so on. I took the quieter route and reread all their childhood books—from nursery rhymes to the Hunger Games series and other novels for young adults.

I was first struck by the prevalence of animals themes in these books. For example, in Eric Kincaid’s superb collection of Nursery Rhymes (1990)—a favourite of our two boys—over forty percent of rhymes concern animals. However, a word search of a book I subsequently wrote on the topic of nature in children’s books called Beasts at Bedtime (2018) showed that I might just as well have called it “Trees at Bedtime.” In addition to the innumerable references to “beasts”, there are almost 200 references to trees in the book.

Trees are represented in these stories in all their remarkable forms: magical trees in fairy tales to trees like JK Rowling’s compellingly violent Whomping Willow at Hogwarts.

It is clear that many writers of children’s stories—especially the so-called classic writers—did not accidentally stumble onto such themes. Beatrix Potter, JRR Tolkien, Ursula LeGuin and many others, had a keen eye for nature, and often had an acute awareness of its devastation. The destruction of trees was a point of moderate obsession for Tolkien who famously wrote, “I take the part of trees as against all their enemies.”

What, I wonder, should we make of this veritable forest of arboreal allusions in children’s stories? Read more »

In the Municipal building on Livingston Street, two floors are reserved for Housing cases. In each court, dozens of people work and wait, a Bosch tableau with an international cast. HPD lawyers work the perimeter. They bring Respondents to the bench, confer with them in the hallway and negotiate with Petitioners on their behalf. HPD attorneys also lunch with landlord’s counsel. There is little ethical or proximate difference between Officers of the Court, save who signs their checks and the pay scales. To a person, they distribute a crushing weight, balancing malfeasance and negligence, plunder and systemic rot. The lasting effect of a day in Housing court isn’t the stipulation Management makes for repairs, nor the tenant’s payment (sometimes, less an abatement), it is feeling that force haul you down and watching others already borne off by it.

In the Municipal building on Livingston Street, two floors are reserved for Housing cases. In each court, dozens of people work and wait, a Bosch tableau with an international cast. HPD lawyers work the perimeter. They bring Respondents to the bench, confer with them in the hallway and negotiate with Petitioners on their behalf. HPD attorneys also lunch with landlord’s counsel. There is little ethical or proximate difference between Officers of the Court, save who signs their checks and the pay scales. To a person, they distribute a crushing weight, balancing malfeasance and negligence, plunder and systemic rot. The lasting effect of a day in Housing court isn’t the stipulation Management makes for repairs, nor the tenant’s payment (sometimes, less an abatement), it is feeling that force haul you down and watching others already borne off by it.

The controversy over the

The controversy over the

The main job of ‘culture’ in a modern society seems to be shielding people from the demands of morality. In its intellectual role it justifies inequality between citizens. In its national history role it gives citizens a delusional sense of their country’s significance and entitlement, followed by a dangerous sense of grievance when this isn’t sufficiently recognised by the rest of the world. In its identitarian role it deflects demands for justification into mere proclamations of fact: ‘Why do we do this or that awful thing?… Because shut up. It is who we are.’

The main job of ‘culture’ in a modern society seems to be shielding people from the demands of morality. In its intellectual role it justifies inequality between citizens. In its national history role it gives citizens a delusional sense of their country’s significance and entitlement, followed by a dangerous sense of grievance when this isn’t sufficiently recognised by the rest of the world. In its identitarian role it deflects demands for justification into mere proclamations of fact: ‘Why do we do this or that awful thing?… Because shut up. It is who we are.’

On July 5 The Nation published a 14 line poem by Anders Carlson-Wee entitled “

On July 5 The Nation published a 14 line poem by Anders Carlson-Wee entitled “ That music and emotion are somehow linked is one of the more widely accepted assumptions shared by philosophical aesthetics as well as the general public. It is also one of the most persistent problems in aesthetics to show how music and emotion are related. Where precisely are these emotions that are allegedly an intrinsic part of the musical experience? Three general answers to this question are possible. Either the emotion is in the musician—the composer or performer—in which case the music is expressing that emotion. Or the emotion is in the music itself, in which case the music somehow embodies the emotion. Or the emotion is in the listener, in which case the music arouses the emotion.

That music and emotion are somehow linked is one of the more widely accepted assumptions shared by philosophical aesthetics as well as the general public. It is also one of the most persistent problems in aesthetics to show how music and emotion are related. Where precisely are these emotions that are allegedly an intrinsic part of the musical experience? Three general answers to this question are possible. Either the emotion is in the musician—the composer or performer—in which case the music is expressing that emotion. Or the emotion is in the music itself, in which case the music somehow embodies the emotion. Or the emotion is in the listener, in which case the music arouses the emotion. sickness was constantly diagnosed for the once powerful idea. And still, after the impressive Sanders campaign of 2016, the electoral success of Jeremy Corbyn in the 2017 general election, as well as the – for many – surprising victory of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the democratic primary in New York, writers continue to assure us that the idea is, if not dead, having serious problems. In any case, the idea of socialism seemed until recently a relic of the industrial past with little to say about contemporary society.

sickness was constantly diagnosed for the once powerful idea. And still, after the impressive Sanders campaign of 2016, the electoral success of Jeremy Corbyn in the 2017 general election, as well as the – for many – surprising victory of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the democratic primary in New York, writers continue to assure us that the idea is, if not dead, having serious problems. In any case, the idea of socialism seemed until recently a relic of the industrial past with little to say about contemporary society. We (the readers of 3QD; I know there are many people who disagree) can take it as given that Alex Jones is a thoroughly evil person. Someone who spreads false statements that the parents of the children killed in the Sandy Hook shooting staged the whole thing deserves lots of bad things happening to him, e.g. lose all the money he has made from the web in a defamation suit that the parents have filed, have people boycott his dietary supplement hoax.

We (the readers of 3QD; I know there are many people who disagree) can take it as given that Alex Jones is a thoroughly evil person. Someone who spreads false statements that the parents of the children killed in the Sandy Hook shooting staged the whole thing deserves lots of bad things happening to him, e.g. lose all the money he has made from the web in a defamation suit that the parents have filed, have people boycott his dietary supplement hoax.

Try it: try talking about the subject of reading without drifting off into how the Internet has changed the way we absorb information. I, along with the majority of people I know whose reading habits were formed long before the advent of digital magazines and newspapers, Google Books, blogs, RSS feeds, social media, and Kindle, usually feel I’m only really reading when it’s printed matter, under a reading lamp, with the screen and phone turned off. But the reality is that I do a vast amount of reading online.

Try it: try talking about the subject of reading without drifting off into how the Internet has changed the way we absorb information. I, along with the majority of people I know whose reading habits were formed long before the advent of digital magazines and newspapers, Google Books, blogs, RSS feeds, social media, and Kindle, usually feel I’m only really reading when it’s printed matter, under a reading lamp, with the screen and phone turned off. But the reality is that I do a vast amount of reading online.