by Guy Elgat

Recently, CNN sent their reporter to cover yet another Trump rally (in Pennsylvania), but this time reporter Gary Tuchman was assigned the more specific task of interviewing Trump supporters who were carrying signs or large cardboard cut-outs of the letter “Q” and wearing T-shirts proclaiming “We are Q”.[1] These Trump supporters were professing their belief in the existence of a person known as Q or QAnon who is supposed to be an anonymous, high-level activist who works from inside the administration with the goal of supporting Trump’s agenda by squashing “deep-state” anti-Trump forces and removing any other obstacle that might stand in the way of consummating the President’s revolutionary vision.

Recently, CNN sent their reporter to cover yet another Trump rally (in Pennsylvania), but this time reporter Gary Tuchman was assigned the more specific task of interviewing Trump supporters who were carrying signs or large cardboard cut-outs of the letter “Q” and wearing T-shirts proclaiming “We are Q”.[1] These Trump supporters were professing their belief in the existence of a person known as Q or QAnon who is supposed to be an anonymous, high-level activist who works from inside the administration with the goal of supporting Trump’s agenda by squashing “deep-state” anti-Trump forces and removing any other obstacle that might stand in the way of consummating the President’s revolutionary vision.

At one point in the interview, in his attempt to probe the beliefs of the Q-ers, as I shall call them, Gary Tuchman challenged one of them and said: “So you don’t have any proof [that Q exists] but that’s what you’re guessing”, in response to which the interviewee said “and you don’t have any proof there isn’t”. In another exchange Tuchman again tried to interrogate a Q-er about her beliefs, saying “Maybe it is not true [that Q exists] because there is no evidence of it…”, in response to which the interviewee shot back: “There hasn’t been any non-evidence yet”.

Upon hearing these retorts many might react with a baffled scoff and dismiss them as not worthy of taking seriously. But though this reaction is at the end of the day warranted – or so I shall argue – it is hard, though important, to explain exactly what is wrong with the Q-ers’ response and why Q-ers might think that it serves their purpose and is thus perfectly legitimate. As we shall see, once we start to reflect on these questions we will find ourselves pretty quickly knee-deep in philosophy, what will bring out again the importance and relevance of philosophy to our everyday lives. Read more »

In the 1960s, in the sleepy little city of Sialkot, almost in no-man’s land between India and Pakistan and of little significance except for its large cantonment and its factories of surgical instruments and sports goods, there were two cinema houses, all within a mile of our house, No. 3 Kutchery Road. Well three to be exact, the third being an improvisation involving two tree trunks with a white sheet slung between them at the Services club and only on Saturday nights.

In the 1960s, in the sleepy little city of Sialkot, almost in no-man’s land between India and Pakistan and of little significance except for its large cantonment and its factories of surgical instruments and sports goods, there were two cinema houses, all within a mile of our house, No. 3 Kutchery Road. Well three to be exact, the third being an improvisation involving two tree trunks with a white sheet slung between them at the Services club and only on Saturday nights. Would I rather go deaf or blind? Every once in a while, I come back to this question in some version or another. Say I had to choose which sense I’d lose in my old age, which would it be? I always give myself, unequivocally, the same answer: I’d rather go blind. I’d rather my world go darker than quieter. I imagine it as a choice between seeing the world and communicating with it; in this hypothetical, communication with the world is all-encompassing, its loss more devastating than the loss of sight. It is perhaps clear from the mere fact that I pose this question that I do not live with a disability involving the senses. Individuals who are vision- or hearing-impaired would have an entirely different take on this question and on the issues I raise below, but hopefully what I write here will go beyond stating my own prejudices.

Would I rather go deaf or blind? Every once in a while, I come back to this question in some version or another. Say I had to choose which sense I’d lose in my old age, which would it be? I always give myself, unequivocally, the same answer: I’d rather go blind. I’d rather my world go darker than quieter. I imagine it as a choice between seeing the world and communicating with it; in this hypothetical, communication with the world is all-encompassing, its loss more devastating than the loss of sight. It is perhaps clear from the mere fact that I pose this question that I do not live with a disability involving the senses. Individuals who are vision- or hearing-impaired would have an entirely different take on this question and on the issues I raise below, but hopefully what I write here will go beyond stating my own prejudices.

The German philosopher

The German philosopher  The idea of ‘good corporate citizenship’ has become popular recently among business ethicists and corporate leaders. You may have noticed its appearance on corporate websites and CEO speeches. But what does it mean and does it matter? Is it any more than a new species of public relations flimflam to set beside terms like ‘corporate social responsibility’ and the ‘triple bottom line’? Is it just a metaphor?

The idea of ‘good corporate citizenship’ has become popular recently among business ethicists and corporate leaders. You may have noticed its appearance on corporate websites and CEO speeches. But what does it mean and does it matter? Is it any more than a new species of public relations flimflam to set beside terms like ‘corporate social responsibility’ and the ‘triple bottom line’? Is it just a metaphor? Learning Objectives. Measurable Outcomes. These are among the buzziest of buzz words in current debates about education. And that discordant groaning noise you can hear around many academic departments is the sound of recalcitrant faculty, following orders from on high, unenthusiastically inserting learning objectives (henceforth LOs) and measurable outcomes (hereafter MOs) into already bloated syllabi or program assessment instruments.

Learning Objectives. Measurable Outcomes. These are among the buzziest of buzz words in current debates about education. And that discordant groaning noise you can hear around many academic departments is the sound of recalcitrant faculty, following orders from on high, unenthusiastically inserting learning objectives (henceforth LOs) and measurable outcomes (hereafter MOs) into already bloated syllabi or program assessment instruments.

Although frequently lampooned as over-the-top, there is a history of describing wines as if they expressed personality traits or emotions, despite the fact that wine is not a psychological agent and could not literally have these characteristics—wines are described as aggressive, sensual, fierce, languorous, angry, dignified, brooding, joyful, bombastic, tense or calm, etc. Is there a foundation to these descriptions or are they just arbitrary flights of fancy?

Although frequently lampooned as over-the-top, there is a history of describing wines as if they expressed personality traits or emotions, despite the fact that wine is not a psychological agent and could not literally have these characteristics—wines are described as aggressive, sensual, fierce, languorous, angry, dignified, brooding, joyful, bombastic, tense or calm, etc. Is there a foundation to these descriptions or are they just arbitrary flights of fancy? He flew so fast and so close to the sun that it took an entire lifetime to fall back to Earth.

He flew so fast and so close to the sun that it took an entire lifetime to fall back to Earth. I recently read Simone Weil for the first time after having come across numerous references to her over the past year. I broke down and bought Waiting for God despite the intimidating and frankly confusing title. I was not disappointed. One of her essays in particular, “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies in View of the Love of God,” has opened and focused my thinking on education and learning in general, whether for children or later in life for the rest of us.

I recently read Simone Weil for the first time after having come across numerous references to her over the past year. I broke down and bought Waiting for God despite the intimidating and frankly confusing title. I was not disappointed. One of her essays in particular, “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies in View of the Love of God,” has opened and focused my thinking on education and learning in general, whether for children or later in life for the rest of us.

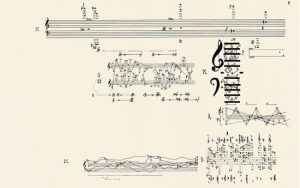

Opera as resistance? Music as re-enchantment?

Opera as resistance? Music as re-enchantment?