by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

The advent of the NPC meme is curious. It’s used as a term of abuse in comment-exchanges, it has occasioned some deep hermeneutics from the cultural Left, and it’s been a cause for escalation particularly by the extreme Right. The political meme of the NPC comes from the world of gaming. It is an abbreviation of non-player character. The point of non-player characters is that they are part of a story being told for the point of the game – a person in need of help, a bartender with some information, or an opponent with a challenge. In tabletop gaming, such as Dungeons and Dragons, the NPCs are played by the Dungeon Master. In that case, there was still an interested human driving the actions of the NPCs. But with electronic games, the NPCs are directed by the computer. They have no inner life nor are they avatars for those who have them. They are merely furniture in the world of the game. Their purpose is to be there to be soaked for information, helped so that they may confer some boon, or vanquished for some treasure, as the case may be. But they have no value or purpose beyond being a foil with which players may tell their own stories.

The application of the term NPC in contemporary internet culture is predicated on the divide between player character and non-player characters. Player characters develop, and they are reasons for which the game world exists. Non-player characters are static, predictable, and mindless; again, they are mere instruments within that world. The division, then, is between those characters who, on the one hand, are conscious, have minds, and can deliberate about what they wish to do, and on the other hand, those characters who are mindless, unconscious, and do not (and perhaps cannot) deliberate about their purposes. NPCs are, then, tools, and players are those who may use them as they see fit.

It is a familiar distinction, in a sense. The old division between those who are asleep and those who are awake is one ancestor. Further, the old term of abuse ‘sheeple’ invokes the idea that there is a less-than-aware group who is systematically misled because of their incapacities or credulity. In fact, the rhetorical force of most consciousness-raising programs requires some such contrast. Enlightenment, for example, contrasts with those who labor in darkness. Being woke contrasts, again, with the slumbering. Those who have been raised up are brought out of a lower consciousness. That’s what consciousness raising is and must be. These metaphors all entail that a change has occurred, one between two contrary states of mind. Read more »

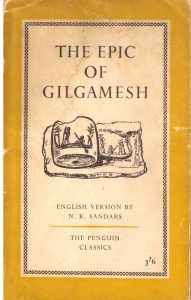

By chance, I chose as holiday reading (awaiting my attention since student days) The Epic of Gilgamesh, a Penguin Classics bestseller, part of the great library of Ashur-bani-pal that was buried in the wreckage of Nineveh when that city was sacked by the Babylonians and their allies in 612 BCE. Gilgamesh is a surprisingly modern hero. As King, he accomplishes mighty deeds, including gaining access to the timber required for his building plans by overcoming the guardian of the forest. But this victory comes at a cost; his beloved friend Enkidu opens by hand the gate to the forest when he should have smashed his way in with his axe. This seemingly minor lapse, like Moses’ minor lapse in striking the rock when he should have spoken to it, proves fatal. Enkidu dies, and Gilgamesh, unable to accept this fact, sets out in search of the secret of immortality, only to learn that there is no such thing. He does bring back from his journey a youth-restoring herb, but at the last moment even this is stolen from him by a snake when he turns aside to bathe. In due course, he dies, mourned by his subjects and surrounded by a grieving family, but despite his many successes, what remains with us is his deep disappointment. He has not managed to accomplish what he set out to do.

By chance, I chose as holiday reading (awaiting my attention since student days) The Epic of Gilgamesh, a Penguin Classics bestseller, part of the great library of Ashur-bani-pal that was buried in the wreckage of Nineveh when that city was sacked by the Babylonians and their allies in 612 BCE. Gilgamesh is a surprisingly modern hero. As King, he accomplishes mighty deeds, including gaining access to the timber required for his building plans by overcoming the guardian of the forest. But this victory comes at a cost; his beloved friend Enkidu opens by hand the gate to the forest when he should have smashed his way in with his axe. This seemingly minor lapse, like Moses’ minor lapse in striking the rock when he should have spoken to it, proves fatal. Enkidu dies, and Gilgamesh, unable to accept this fact, sets out in search of the secret of immortality, only to learn that there is no such thing. He does bring back from his journey a youth-restoring herb, but at the last moment even this is stolen from him by a snake when he turns aside to bathe. In due course, he dies, mourned by his subjects and surrounded by a grieving family, but despite his many successes, what remains with us is his deep disappointment. He has not managed to accomplish what he set out to do. On his journey, Gilgamesh meets the one man who has achieved immortality, Utnapishtim, survivor of a flood remarkably similar, even in its details, to the Flood in the Bible. Reading of this sent me back to Genesis, and hence to two other books,

On his journey, Gilgamesh meets the one man who has achieved immortality, Utnapishtim, survivor of a flood remarkably similar, even in its details, to the Flood in the Bible. Reading of this sent me back to Genesis, and hence to two other books, Comparing Hebrew with Cuneiform may seem like a suitable gentlemanly occupation for students of ancient literature, but of no practical importance. On the contrary, I maintain that what emerges is of major contemporary relevance.

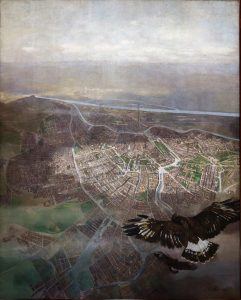

Comparing Hebrew with Cuneiform may seem like a suitable gentlemanly occupation for students of ancient literature, but of no practical importance. On the contrary, I maintain that what emerges is of major contemporary relevance. When architect Otto Wagner commissioned this large painting by Carl Moll for the Kaiser’s personal railroad station in Vienna in 1899, he might not have seen the irony of an eagle’s view of the city. View of Vienna from a Balloon envisions a future beyond rails in which a bird shows the way to a whole new way of looking at landscape, one that would renew the way we view nature itself, hardly more than a 100 years later. If that painting were done today, the eagle would be replaced by a small four-cornered device with a camera and four rotary blades to keep it aloft: the drone.

When architect Otto Wagner commissioned this large painting by Carl Moll for the Kaiser’s personal railroad station in Vienna in 1899, he might not have seen the irony of an eagle’s view of the city. View of Vienna from a Balloon envisions a future beyond rails in which a bird shows the way to a whole new way of looking at landscape, one that would renew the way we view nature itself, hardly more than a 100 years later. If that painting were done today, the eagle would be replaced by a small four-cornered device with a camera and four rotary blades to keep it aloft: the drone.

This year – 2018 – marks something truly auspicious. This is the semi-centennial of the invention of the Zombie. In these fifty years, let’s face it, we have been completely overrun. Zombies are everywhere. They are in our movies, tv shows, books, and comic books, plus, out here in the real world where the Center for Disease Control has a comprehensive Zombie preparedness and education plan and there are Zombie-walks, Zombie-conventions, and, anyway, didn’t you see them this Halloween? The most popular Zombie tv show, “The Walking Dead”, has been streaming for almost ten years – and the comic book it is based on is still going strong. At least one Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award winning author has written a straight-up zombie novel – Colson Whitehead’s “Zone One”. So, what’s with all the Zombies?

This year – 2018 – marks something truly auspicious. This is the semi-centennial of the invention of the Zombie. In these fifty years, let’s face it, we have been completely overrun. Zombies are everywhere. They are in our movies, tv shows, books, and comic books, plus, out here in the real world where the Center for Disease Control has a comprehensive Zombie preparedness and education plan and there are Zombie-walks, Zombie-conventions, and, anyway, didn’t you see them this Halloween? The most popular Zombie tv show, “The Walking Dead”, has been streaming for almost ten years – and the comic book it is based on is still going strong. At least one Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award winning author has written a straight-up zombie novel – Colson Whitehead’s “Zone One”. So, what’s with all the Zombies?

“They all go the same way. Look up, then down and to the left,” the EMT said. “Always.”

“They all go the same way. Look up, then down and to the left,” the EMT said. “Always.”

In Tian Shan mountains of the legendary snow leopard, errant wisps of mist float with the speed of scurrying ghosts, there is a climbers’ cemetery, Himalayan Griffin vultures and golden eagles are often sighted, though my attention is completely arrested by a Blue whistling thrush alighting on a rock— its plumage, its slender, seemingly weightless frame, and its long drawn, ventriloquist song remind me of the fairies of Alif Laila that were turned to birds by demons inhabiting barren mountains.

In Tian Shan mountains of the legendary snow leopard, errant wisps of mist float with the speed of scurrying ghosts, there is a climbers’ cemetery, Himalayan Griffin vultures and golden eagles are often sighted, though my attention is completely arrested by a Blue whistling thrush alighting on a rock— its plumage, its slender, seemingly weightless frame, and its long drawn, ventriloquist song remind me of the fairies of Alif Laila that were turned to birds by demons inhabiting barren mountains.

On a recent windy morning, walking past the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument on West 89th Street in New York City, seeing the flag at half mast, just days before the

On a recent windy morning, walking past the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument on West 89th Street in New York City, seeing the flag at half mast, just days before the  April 2018: ‘Tis the Season of Giddiness in Democratlandia. Republicans are saddled with a widely despised President and riven by internal dissension. The Republican leadership in Congress is lurching from fiasco to fiasco – interrupted briefly by one great “success” on tax cuts. The zombie candidates of the Tea Party are still stalking establishment Republicans across the land. And, somewhere in his formidable fastness, the Great Dragon Mueller is winding up for the fiery breath that will consume the world of Trumpism like a paper lantern. And a Blue Wave – nay, a Tsunami – is headed towards the Republicans in Congress, looking to engulf them in November.

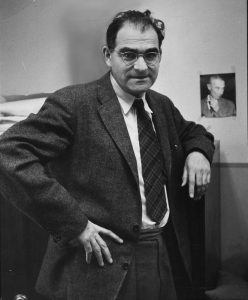

April 2018: ‘Tis the Season of Giddiness in Democratlandia. Republicans are saddled with a widely despised President and riven by internal dissension. The Republican leadership in Congress is lurching from fiasco to fiasco – interrupted briefly by one great “success” on tax cuts. The zombie candidates of the Tea Party are still stalking establishment Republicans across the land. And, somewhere in his formidable fastness, the Great Dragon Mueller is winding up for the fiery breath that will consume the world of Trumpism like a paper lantern. And a Blue Wave – nay, a Tsunami – is headed towards the Republicans in Congress, looking to engulf them in November. Victor Weisskopf (Viki to his friends) emigrated to the United States in the 1930s as part of the windfall of Jewish European emigre physicists which the country inherited thanks to Adolf Hitler. In many ways Weisskopf’s story was typical of his generation’s: born to well-to-do parents in Vienna at the turn of the century, educated in the best centers of theoretical physics – Göttingen, Zurich and Copenhagen – where he learnt quantum mechanics from masters like Wolfgang Pauli, Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr, and finally escaping the growing tentacles of fascism to make a home for himself in the United States where he flourished, first at Rochester and then at MIT. He worked at Los Alamos on the bomb, then campaigned against it as well as against the growing tide of red-baiting in the United States. A beloved teacher and researcher, he was also the first director-general of CERN, a laboratory which continues to work at the forefront of particle physics and rack up honors.

Victor Weisskopf (Viki to his friends) emigrated to the United States in the 1930s as part of the windfall of Jewish European emigre physicists which the country inherited thanks to Adolf Hitler. In many ways Weisskopf’s story was typical of his generation’s: born to well-to-do parents in Vienna at the turn of the century, educated in the best centers of theoretical physics – Göttingen, Zurich and Copenhagen – where he learnt quantum mechanics from masters like Wolfgang Pauli, Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr, and finally escaping the growing tentacles of fascism to make a home for himself in the United States where he flourished, first at Rochester and then at MIT. He worked at Los Alamos on the bomb, then campaigned against it as well as against the growing tide of red-baiting in the United States. A beloved teacher and researcher, he was also the first director-general of CERN, a laboratory which continues to work at the forefront of particle physics and rack up honors.

When you consume a meal, do you eat cow or beef? Yes, these are the same, especially considering where they end up, but we tend to think of the cow as the beginning of this particular process, and the beef as the product. More of these pairings include calf/veal, swine or pig/pork, sheep/mutton, hen or chicken/poultry, deer/venison, snail/escargot.

When you consume a meal, do you eat cow or beef? Yes, these are the same, especially considering where they end up, but we tend to think of the cow as the beginning of this particular process, and the beef as the product. More of these pairings include calf/veal, swine or pig/pork, sheep/mutton, hen or chicken/poultry, deer/venison, snail/escargot.