by Thomas O’Dwyer

When a plane lands at Larnaca in Cyprus, as it rolls past the control tower one can glimpse on a misty horizon the lone pyramid of Stavrovouni mountain. The ugly airport tower then obscures the steep mountain and the ancient monastery on its summit. It could be a metaphor for modernity obliterating the spirit of places that once seemed mysterious and eternal.

It’s an hour’s drive from the airport to the sprawling concrete capital Nicosia and up and over the green passes of the Kyrenia mountain range. Then it’s a right turn east along the northern Mediterranean coast to the hillside village of Bellapais. A remarkable 12th-century Gothic abbey dominates the village and a couple of Crusader castles brood on the mountain ridge high above it. Even the names carry a whiff of ancient Gothic Europe – Buffavento, Hilarion, Bellapais. Carob, mulberry and cypress trees crowd around the ruins as they did when knights roamed the hills.

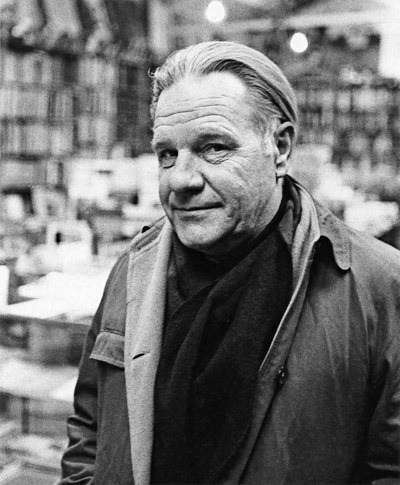

A few hundred metres up a steep path from the abbey is a small house, once traditional, now modernised. The abbey and the cottage are responsible for the tawdry trinket shops and banal tourist cafes that have all but wiped out the old village tavernas. The splendid abbey is an obvious attraction, but the unremarkable cottage? For the literary-minded, it has an equal fascination. In it was written one of the great portraits of a city in 20th-century English literature. Here in the early 1950s Lawrence Durrell reimagined and immortalised Alexandria of Egypt. It joined the Dublin of James Joyce and the Paris of Marcel Proust in literary legend.

A recent British TV series “The Durrells” has introduced the 80-year-old saga of this oddball family to new generations. (In America, PBS airs it as “The Durrells in Corfu”). In 1935 a poor British widow, Louisa Durrell, abruptly moved her young family of four from Bournemouth to Corfu island. She replaced a wet and bleak England with the dazzling light and warmth of a Greek lifestyle. This happy exile produced two Durrell authors, the funny zoologist Gerald and the literary giant Lawrence.

“I write literature,” Lawrence once told a BBC interviewer. “My brother writes books that people read.” Lawrence’s book sales never did reach the dizzy heights achieved by those of his brother. Gerald’s hilarious My Family and Other Animals is the basis for the TV series. But Gerald never won the critical acclaim that Lawrence did for The Alexandria Quartet – Justine, Balthazar, Mountolive and Clea.

In 1941, the Durrells had to flee Greece ahead of the advancing Nazi army. Lawrence separated from his first wife Nancy and moved to Alexandria, Egypt. He took a job as press attaché in the British Information Office. He also met the beautiful Eve Cohen, a Jewish Alexandrian and the model for Justine in The Alexandria Quartet. He married her in 1947 and they had a daughter, Sappho. After a year in Argentina with the British Council cultural mission, Durrell was sent to Belgrade, Yugoslavia, as press attaché. In 1952, Eve went to England to be hospitalised for mental health problems. Durrell moved to Cyprus with the year-old Sappho.

“I have managed to put what little money I have (had) into a tiny but lovely house in a tumbledown village built round a huge ruined abbey,” he wrote to his friend, the explorer Freya Stark. “A lovely village. Cyprus is rather a lovely, spare, big bland sexy island – totally unlike Greece with a weird charm of its own.”

In the opening paragraphs of Justine, the first book of the quartet, Durrell writes:

“I have escaped to this island with a few books and the child … At night when the wind roars and the child sleeps quietly in its wooden cot by the echoing chimney-piece, I light a lamp and walk about, thinking of my friends … I return link by link along the iron chains of memory to the city which we inhabited so briefly together: the city which used us as its flora – precipitated in us conflicts which were hers and which we mistook for our own: beloved Alexandria!”

No one has been more associated with the aesthetics of landscapes than Durrell. “Spirit of place” is a concept that moves through all his writing and to which he returns again and again. Spirit of Place was the title of one of his books and of a documentary he did with the BBC about Corfu.

In the post-war period, British-occupied Cyprus was an East Mediterranean cross-road. It was where philhellenes and Middle East travellers rested from their journeys or wrote their books. Durrell was soon awash with visitors to his “artsy cottage” in Bellapais. Many of these were old friends from his own travels – Freya Stark, poet George Seferis (who later won a Nobel Prize), historian Lord Kinross, and adventurer Patrick Leigh Fermor. A fluent Greek speaker, Durrell soon accumulated new friends on the island. But he had burned his boats on leaving the British Council and he was running out of money. He took a job teaching English at Nicosia’s leading Greek high school, hobbling his plans to write full time.

He wrote to American author Henry Miller, with whom he had become close friends in Greece:

“For the last two months we have been building my little house into something beautiful. I haven’t even had a table to write on. Besides, started an arduous job as a teacher which involves getting up at five every morning and working till two – with a 30-mile drive thrown in. In addition I have been working at a new manuscript “Justine” which is something really good I think. A novel about Alexandria – four dimensional. Never have I worked under such adverse conditions but my enchanting daughter Sappho is well, she is adorable.”

Even with the work, and the child, and the visitors, he found time for his exploration of what makes a place “a presence.” Durrell considered himself to be a poet (T.S. Eliot was his publisher’s editor and his early mentor and critic). To his readers, he was an avant-garde novelist. But today his works in print are more likely to sit in the travel sections of bookshops. Durrell believed that the aim of travel was to strip away the increasing sameness of places. To do that, one had to connect with those elements that draw an enriching experience from every culture.

Durrell was born and spent an early childhood in India and though never religious, he declared that he had “a Tibetan mind,” attuned to Buddhism. Using scientific metaphor, he said that our view of the universe had changed when we discovered that the ultimate tiny atomic particle was not something hard, but a wave. “Our solid world may be real, but is also illusory and infinite. The spirit of place moves over the land like the spirit of God upon the face of the waters in Genesis,” he said in an interview.

Pneuma was the ancient Greek word for breath and also a metaphor for spirit or soul. Durrell often referred to a breeze rustling the Greek landscape as its pneuma, its spirit. An aware person drawing their breath in the landscape was merging their own spirit with that of the place.

“It is a pity indeed to travel and not get this essential sense of landscape values. You do not need a sixth sense for it,” he wrote in Spirit of Place. “It is there if you just close your eyes and breathe softly; you will hear the whispered message, ‘I am watching you – are you watching yourself in me?’ Most travelers hurry too much, burdened with too much factual information … To extract the essence of a place you don’t need knowledge; you need observation and a sort of science of intuitions. If you just get as still as a needle, you’ll be there.”

What he called “Greekness” fascinated Durrell – the non-sentimental essence of Greek landscapes – because that was the culture he loved most. Curiously, there was one culture he dismissed with contempt – the English. “God spare me from the English death,” he said in an interview. “English life is like an autopsy, cold and bleak. It has no spirit; it is so, so dreary.” The only English-language cultures he admired were in the Celtic nations of Scotland, Wales and Ireland.

“The [Greek] people struck me as so fantastic. It was as if Ireland had been towed down and plonked into the Mediterranean. Because the place isn’t Spanish, which has a sort of sombre quality, and it isn’t Italy, which has an operatic quality. It has a kind of innocent, wide-eyed, passionate, romantic craziness. It went right to my heart,” Durrell said in his BBC documentary “Spirit of Place.”

“There are islands off Dubrovnik that are as beautiful as the Greek islands, but they seem to have nothing more. Ancient Greek mythology is always at your elbow in Corfu. It’s a great seduction because you do feel the presence of Aphrodite and the spirit of place. It’s not sentimental to realise that in every phrase the Greeks use today, two out of five words are Homeric words. They come from Plato. Here you feel the possibility of living the maximum number of lives allotted to you, so to speak. Here you’re the cat.” He noted that village Greeks themselves “sometimes are not aware of the ancientness of their customs.” But it is there. In simple unselfconscious village weddings, he said, one could feel their whole story.

“They go back through Byzantium into ancient life. A wedding is ceremony and glad-rags and revelry and dancing all night. In the old costumes, villagers look as colourful as a pack of cards. The best man walks out with the bride on his arm, and she is taken away, and the festive dances begin. It’s all very Homeric. Dancing is never a performance so much as the passing on of an enigmatic knowledge which the musicians have summoned up from below the earth. It flows outward, and the dancing feet draw life’s circles, stitch by stitch like a woven fabric.”

In Cyprus, he set out to explore the landscape of his new village. “My books are always about living in places, not just rushing through them … the important determinant of any culture is after all – the spirit of place”. He rewarded the island years later with its own Durrell classic – Bitter Lemons. In it, he chronicled the final chaotic and violent end to British rule. But like his other “island books” about Greece, his real aim was to reveal that elusive spirit of the place to future travellers.

“The feeble insinuations of a shepherd’s flute directed my steps to the little wine-store of Clito one fine tawny-purple dusk. The sea had been drained of its colors, and the last colored sails had begun to flutter across the harbor-bar like homesick butterflies,” he writes in Bitter Lemons about finding a new tavern in the little harbour of Kyrenia.

The muktar – village leader – warns the writer not to assume he can work in Bellapais. “I must warn you, if you intend to try and work, not to sit under the Tree of Idleness. You have heard of it?” This giant mulberry tree dominated Bellapais square and its cafe where the village men (but not women) gathered daily to gossip and discuss news events. “Its shadow incapacitates one for serious work,” said the muktar. “By tradition the inhabitants of Bellapais are regarded as the laziest in the island. They are all landed men, coffee-drinkers and card-players. That is why they live to such ages. Nobody ever seems to die here. Ask Mr. Honey the grave-digger. Lack of clients has driven himself into a decline.”

Durrell often seemed to be escaping from what the poet Philip Larkin called “the importance of elsewhere” – “Here no elsewhere underwrites my existence.” In his BBC documentary, he said: “When you get to a place the first thing you think is gosh, I would (or I wouldn’t) like to live here. But once you find yourself thinking I wouldn’t mind dying here, then you’ve found it.”

In Bellapais he produced Justine, crafting his mythical Alexandria, and gave Sappho an idyllic childhood. But, as in Corfu with the arrival of Nazis, the spirits of a place can quickly turn malignant, and Durrell really did mind dying there. In 1955, armed conflict began between the British and a Cypriot guerrilla organisation. As the crisis expanded, Durrell accepted the post of press spokesman for the British in Nicosia. It was a wretched position for a man who was both a passionate philhellene and a dutiful British expatriate. His beloved Greek people stopped looking him in the eye and turned their backs on him, and there were rumours of guerrilla plans to kill him. He came close to being shot in his local tavern. He also feared that his village friends were now in danger for associating with an Englishman. (About 500 Britons, Greeks and Turks died in the conflict before Cyprus won its independence in 1960).

When he settled in Bellapais, Durrell had written to Henry Miller: “Life on an island, however rich, is circumscribed, and one does well to portion out one’s experiences. Taken leisurely, with all one’s time at one’s disposal Cyprus could, I calculate, afford one a minimum of two years reckoned in terms of novelty; hoarded as I intended to hoard it, it might last anything up to a decade.”

He didn’t have a decade. In 1956, Durrell abandoned his house in Bellapais and left for England, where in 1957 he wrote his Cyprus memoir in the bitter aftertaste of his flight from there. He soon resettled in a Provence village in the south of France, where he remained writing until his death in 1990. Five years before that, in 1985, his daughter, the “adorable Sappho,” a poet who may have inherited her mother’s mental illness, hanged herself at the age of 33.

Lawrence Durrell never returned to Cyprus. His once “tiny but lovely” Bellapais house has been extended and modernised. Over-gentrified, it stands by a newly paved road and is rented to tourists for more per week than the 300 pounds he paid to buy it. It has a bright lemon-yellow sign on the wall which reads “Bitter Lemons Street.”

Whatever spirit it once had has gone elsewhere.