by Joshua Wilbur

Repetition, in itself, is neither good nor bad. Everything repeats. “Nature is an endless combination and repetition of very few laws,” said Emerson. Seasons come, and seasons go.

But what’s true for seasons isn’t true for people. We tend to prefer some forms of repetition to others. At its best, repetition is a great source of comfort and a precondition for mastering any task. The familiar rhythms of the Sunday church service are a balm to many, and it takes years of practice to throw a 98 mile-per-hour fastball that cuts in on a hitter’s hands at just the right moment.

At its worst, repetition means monotony and aimless toil: Sisyphus pushing his boulder up the hill for all eternity. Freud wrote of our “compulsion to repeat” the past, sensing that reenactment lies at the heart of everyday neuroticism, psychological trauma, and the most unnerving displays of madness—“All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy,” writes Jack Torrance, a thousand times over, in The Shining.

In between these two extremes—between the master and the madman—repetition provides the unglamorous but necessary foundation of daily life. It’s the soundtrack of childhood: brush your teeth, tie your shoes, finish your homework, eat your dinner, and so on. By the time a person reaches adulthood, she has internalized an incalculable number of habits: some good, some bad, but most avoiding the sureness of a positive or negative judgement. Thanks to our neurological adaptiveness, we are constantly slipping into patterns without realizing it, and the unrelenting expansion of consumer tech has only opened more avenues for our habitual instincts.

Of all my habits, I’m most conflicted about my routine with my iPhone, repeated dozens of times throughout the day. It might sound familiar to you. I pick up my phone, unlock the homescreen, check for and respond to text messages, check for and respond to emails, and, finally, check an app or two for the latest headlines. At this point, I might tumble further down the rabbit hole or put away the phone until the next sequence.

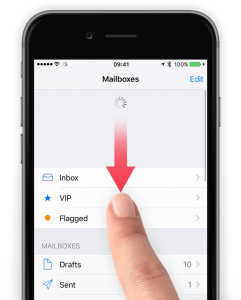

Behind all of this check-check-checking is elegant design. From start to finish, my actions are guided by the hidden forces of user interface. One mechanism, in particular, looms over this cycle of repetition and reward. The “pull-to-refresh” gesture was created by software developer Loren Brichter in 2009. First used in Twitter feeds, the gesture is now pervasive in smartphone apps, as simple as it is addictive: pull down on the screen, wait for the buffering circle, and see what content awaits.

Last October, The Guardian interviewed a number of Silicon Valley employees, including Brichter, about the pernicious influence of addictive technologies. In the article, Tristan Harris, a Google employee turned industry critic, sums up the experience of pull-to-refresh: “Each time you’re swiping down, it’s like a slot machine. You don’t know what’s coming next. Sometimes it’s a beautiful photo. Sometimes it’s just an ad.”

According to Brichter himself, the pull-to-refresh gesture is far from necessary. An application can update its content without a user “pulling” anything, as many apps do; pull-to-refresh “could easily retire,” Brichter says. But the slot machine effect—pull, wait, reward—is satisfying. In my own regular cycle, I perform the gesture in my iPhone’s email, Reddit, and New York Times apps. If I’m following a developing news story or waiting for an email, I’ll swipe down again and again, feverish for that quick hit of information.

What am I so eager for? What’s my reward?

More often than not, it’s nothing special. An update on a political scandal. A reminder about the enrollment window for insurance benefits. A recap of which teams won and which stocks were up.

Of course, there are occasionally more significant revelations. News of personal successes and setbacks are dramatically revealed after a second or two in email purgatory. Moments of broader social significance—from national elections to natural disasters—are closely followed, lest I miss something important.

In each case, what I’m really craving is a particular kind of knowledge. I want to know what’s happening right now, and, barring internet problems, pull-to-refresh always delivers. Twenty minutes ago is ancient history; it’s simply not good enough. I need to know what’s going on now: personally, professionally, and culturally.

No doubt, there are benefits to this constant refreshing. I’m generally well-informed. I’m socially connected. But this is addiction all the same, and an odd form at that: it’s an addiction to the present moment. I’m addicted to right now.

What’s wrong with this behavior? Isn’t “living in the now” supposed to be a good thing? Don’t the evangelists of mindfulness and meditation—who continue to grow in number—endlessly preach the value of “being in the moment” and ignoring past and future?

“The only place you can experience the flow of life is the Now,” writes Eckhart Tolle, author of The Power of Now. Jon Kabat-Zinn, the author of Wherever You Go, There You Are and popularizer of secular mindfulness since the 1970s, says that “we take care of the future best by taking care of the present now.” The now is what I encounter anew with every refresh of an iPhone app, right?

Obviously, there’s a problem with this logic: it confuses two different meanings of “now.” The now of the news, the “pull-to-refresh Now,” is a constantly shifting conception of how things stand in the world at large; it’s relational and always tied up with other people. The internet has securely fastened us to this cultural present.

On the other hand, the “Zen/Zinn Now” refers to what’s accessible in immediate experience. It’s rooted in mental and bodily sensations (which are actually one and the same) and theoretically independent of all culture. This latter vision of a local, corporeal “now” isn’t limited to Eastern-derived traditions. The European phenomenologists, who dictated the course of 20th century philosophy, echoed note-for-note the lessons of the Zen masters: experience always comes before categorization— “existence precedes essence,” as Sartre formulated— and it should be attended to with conscious effort. You can try this yourself. Walk through any familiar location, and pretend that you’ve never been there before. Your manner of looking will quickly change, ordinary things (stripped of usual associations) will appear suddenly bizarre, and you will be experiencing “now” in the manner of a Buddha or a Heidegger.

The conclusion should be clear: with every click, text, like, refresh, share, tweet, and post, we trade a “good Now” for a “bad Now.” And the prescription, the always available fix, is to simply stay in the immediate now of your surroundings. In any given moment, you can live in the world of sights and smells and sounds, or you can plunge into the world of language, thoughts, news alerts, and status updates. The choice, as they say, is yours.

Unfortunately, habits are hard to break. And the habit of preferencing the cultural “now” over the real “now” is so ingrained and so abstract as to be largely invulnerable to whatever fleeting philosophical insights we may have. Total enlightenment sounds wonderful, but I’m still going to check the score of the game. And I suspect that there are good explanations from an evolutionary perspective for our obsession with information. Knowing “the latest” surely provides a competitive advantage.

I wonder if I can live in both worlds at once. Can I have my cake and eat it too?

I’ll try an experiment. From now on, I will mindfully refresh my three email accounts. I will pull down on the screen only once and wait patiently for the headlines to load. I will breathe deeply as I scroll through the unremitting stream of words and images. If this sounds a bit ridiculous, it’s worth wondering why. Maybe it’s that these two ways of approaching the world are in fundamental conflict with each other. Transitioning from one sort of “now” to another is a very difficult switch to flip.

A recent article at The Ringer by Mike Powell, “Meditation in the Time of Disruption,” targets the same irony. “Can you really unplug and reset while tied to an app on your phone?,” he wonders. Apps like Headspace, Calm, and Insight Timer promise to deliver us from evil, but they’ve also made a deal with the devil in coming to us through a screen. The medium sullies the message.

I agree, though, that such interventions are valuable and much needed. Powell writes, “The phones aren’t going away; the only thing we can control is our relationship to them.” With the coming expansion of augmented reality, it will continue to be a tough fight, particularly since developers clearly understand our repetitive inclinations. Last year, Sean Parker, the ex-Facebook president, openly admitted that the company exploited “a vulnerability in human psychology.”

For what it’s worth, Loren Brichter, the developer who created pull-to-refresh, has his own regrets:

“Smartphones are useful tools,” he says. “But they’re addictive. Pull-to-refresh is addictive. Twitter is addictive. These are not good things. When I was working on them, it was not something I was mature enough to think about. I’m not saying I’m mature now, but I’m a little bit more mature, and I regret the downsides.”

Clearly, the downsides aren’t enough to dissuade us. Instant information is a powerful lure and a convenient distraction from the examined life. Whichever view you take, the result is the same: there is only now, and it is always refreshed.