by Ashutosh Jogalekar

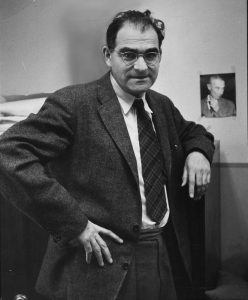

Victor Weisskopf (Viki to his friends) emigrated to the United States in the 1930s as part of the windfall of Jewish European emigre physicists which the country inherited thanks to Adolf Hitler. In many ways Weisskopf’s story was typical of his generation’s: born to well-to-do parents in Vienna at the turn of the century, educated in the best centers of theoretical physics – Göttingen, Zurich and Copenhagen – where he learnt quantum mechanics from masters like Wolfgang Pauli, Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr, and finally escaping the growing tentacles of fascism to make a home for himself in the United States where he flourished, first at Rochester and then at MIT. He worked at Los Alamos on the bomb, then campaigned against it as well as against the growing tide of red-baiting in the United States. A beloved teacher and researcher, he was also the first director-general of CERN, a laboratory which continues to work at the forefront of particle physics and rack up honors.

Victor Weisskopf (Viki to his friends) emigrated to the United States in the 1930s as part of the windfall of Jewish European emigre physicists which the country inherited thanks to Adolf Hitler. In many ways Weisskopf’s story was typical of his generation’s: born to well-to-do parents in Vienna at the turn of the century, educated in the best centers of theoretical physics – Göttingen, Zurich and Copenhagen – where he learnt quantum mechanics from masters like Wolfgang Pauli, Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr, and finally escaping the growing tentacles of fascism to make a home for himself in the United States where he flourished, first at Rochester and then at MIT. He worked at Los Alamos on the bomb, then campaigned against it as well as against the growing tide of red-baiting in the United States. A beloved teacher and researcher, he was also the first director-general of CERN, a laboratory which continues to work at the forefront of particle physics and rack up honors.

But Weisskopf also had qualities that set him apart from many of his fellow physicists; among them were an acute sense of human tragedy and triumph and a keen interest in music and the humanities that allowed him to appreciate human problems and connect ideas from various disciplines. He was also renowned for being a wonderfully warm teacher. Many of these qualities are on full display in his wonderful, underappreciated memoir titled “The Joy of Insight: Passions of a Physicist”.

The memoir starts by describing Weisskopf’s upbringing in early twentieth century Vienna, which was then a hotbed of revolutions in science, art, psychology and music. The scientifically inclined Weisskopf came of age at the right time, when quantum mechanics was being developed in Europe. He was fortunate to study first at Göttingen which was the epicenter of the new developments, and then in Zurich under the tutelage of the brilliant and famously acerbic Wolfgang Pauli. It was Göttingen where Max Born and Heisenberg had invented quantum mechanics; by the time Weisskopf came along, in the early 1930s, physicists were in a frenzy to apply quantum mechanics to a range of well known, outstanding problems in nuclear physics, solid state physics and other frontier branches of physics. Weisskopf made important contributions to quantum electrodynamics which underlies much of modern physics.

Pauli who was known as the “conscience of physics” was known for his sharp tongue that spared no one, but also for his honesty and friendship. Weisskopf’s first encounter with Pauli was typical:

“When I arrived at the Institute, I knocked at the door of Pauli’s office until I heard a faint voice saying, “Come in”. There at the far end of the room I saw Pauli sitting at his desk. “Wait, wait”, he said, “I have to finish this calculation.” So I waited for a few minutes. Finally, he lifted his head and said, “Who are you?” I answered, “I am Weisskopf. You asked me to be your assistant.” He replied, “Oh, yes. I really wanted (Hans) Bethe, but he works on solid state theory, which I don’t like, although I started it.”…

Pauli gave me some problem to study – I no longer remember what it was – and after a week he asked me what I had done about it. I showed him my solution, and he said, “I should have taken Bethe after all.”…

“One evening at six o’clock, my usual quitting time, Bohr and I were still deep in discussion. I had an appointment that night and had to leave promptly, so Bohr walked me to the streetcar stop, about five minutes from his house. We walked and he talked. When we got there, the streetcar was approaching. It stopped and I climbed on to the steps. But Bohr was not finished. Oblivious to the people sitting in the car, he went right on with what he had been saying while I stood on the steps. Everyone knew who Bohr was, even the motorman, who made no attempt to move to start the car. He was listening with what seemed like rapt attention while Bohr talked for several minutes about certain subtle properties of the electron. Finally Bohr was through and the streetcar started. I walked to my seat under the eyes of the passengers, who looked at me as if I were a messenger from a special world, a person chosen to work with the great Niels Bohr.”

“My visits to Viki’s class in quantum mechanics at MIT were, in every way, a culture shock. The class and the classroom were both huge—at least a hundred students. Weisskopf was also huge, at least he was tall compared to the diminutive (Julian) Schwinger. I do not think he wore a jacket, or if he did, it must have been rumpled. Schwinger was what we used to call a spiffy dresser.

Weisskopf’s first remark on entering the classroom, was “Boys [there were no women in the class], I just had a wonderful night!” There were raucous catcalls of “Yeah Viki!” along with assorted outbursts of applause. When things had quieted down Weisskopf said, “No, no, it’s not what you think. Last night, for the first time, I really understood the Born approximation.” This was a reference to an important approximation method in quantum mechanics that had been invented in the late 1920s by the German physicist Max Born, with whom Weisskopf studied in Göttingen. Weisskopf then proceeded to derive the principal formulas of the Born approximation, using notes that looked as if they had been written on the back of an envelope.

Along the way, he got nearly every factor of two and pi wrong. At each of these mistakes there would be a general outcry from the class; at the end of the process, a correct formula emerged, along with the sense, perhaps illusory, that we were participating in a scientific discovery rather than an intellectual entertainment. Weisskopf also had wonderful insights into what each term in the formula meant for understanding physics. We were, in short, in the hands of a master teacher.”

“I can best describe the joy of insight as a feeling of aesthetic pleasure. It kept alive my belief in humankind at a time when the world was headed for catastrophe. The great creations of the human mind in both art and science helped soften the despair I was beginning to feel when I experienced the political changes that were taking place in Europe and recognized the growing threat of war.”

“During the 1960s I tried to recall my emotions of those days for the students who came to me during the protests against the Vietnam War. This, and other political issues, preoccupied them, and they told me that they found it impossible to concentrate on problems of theoretical physics when so much was at stake for the country and for humanity. I tried to convince them – not too successfully – that especially in difficult times it was important to remain aware of the great enduring achievements in science and in other fields in order to remain sane and preserve a belief in the future. Apart from these great contributions to civilization, humankind offers rather little to support that faith.”

In other words, it is important to keep the flame burning precisely when the wind is blowing. When so much of the world can seem to be chaotic, dangerous and unpredictable, Weisskopf’s ode to the ‘most precious thing that we have’ is worth keeping in mind. His spirit should live on.