by Christopher Bacas

Guinea and Redhead were part of a large food chain. Beyond campus’ freshly-baked sidewalks, a Cowboy Mafia ferried contraband from the south. They landed small prop planes on ranch land outside of town, cut powder with dental anesthetics and broke up the bales. Their wares clumped on our cafeteria trays and glinted in tiny screw-top bottles. The capo, a local big-hat business man,who ran a palatial kicker-dance hall and owned the ranch. That legit business and his crew’s discipline kept them out of jail. Maybe a hat full of cash in the bargain.

Guinea and Redhead were part of a large food chain. Beyond campus’ freshly-baked sidewalks, a Cowboy Mafia ferried contraband from the south. They landed small prop planes on ranch land outside of town, cut powder with dental anesthetics and broke up the bales. Their wares clumped on our cafeteria trays and glinted in tiny screw-top bottles. The capo, a local big-hat business man,who ran a palatial kicker-dance hall and owned the ranch. That legit business and his crew’s discipline kept them out of jail. Maybe a hat full of cash in the bargain.

My Trumpet buddy shared an apartment in a low-rise student complex. Trumpet’s Roomie was in with the Cowboys. I found out when I made a visit. From outside, the shitty drywall construction leaked sound and odors like a window screen. Inside, eucalyptus gas wrapped around my head. I knew Roomie a little. He didn’t seem to remember. Wide-eyed, fidgeting, he appraised me.

“You cool?”

I reckoned I was. In his bedroom, he kicked aside some laundry and slid open a door. On the floor, a bulging black Hefty bag yawned. Inside, Tolkein magic: lichen grown thigh-deep, whispering in shadow. Despite mind-expanding potential, there was no joy in babysitting a large ingot of fools’ gold.

“L-L-Look at this shit! They expect me t-t-to sell all this.”

He didn’t actually have a stutter, but the enormity of the task made him babble. My thinking, much clearer, certainly no one would miss a handful…

Roomie stayed tight with those cats long after he left the apartment with Trumpet guy. He got into powders. His goods came pretty stepped on, promoting self-immolating paranoia. A fate he succumbed to after dipping deep into his own supply. One day, he dropped by my place to treat me. Once we got nice and jittery, he stood beside the curtains and peeked through a gap.

“Hey man, whose white truck is that?”

“I don’t know”

“You never saw it before?”

“I don’t know.”

“Fuck. Was it here before I got here?”

“I wasn’t looking.”

“Shit. He might have followed me. You really don’t know?” He laughed.

Roomie had a laugh like a pig’s snort.

“It’s cool. I’m just paranoid”

His solution to anxiety, more candy, of course. He’d come by not to treat me, but to get away from “cops” watching his place. Now, he thought they were watching mine. We survived the afternoon, but if I had a weapon, he would have asked me to cover him as he left.

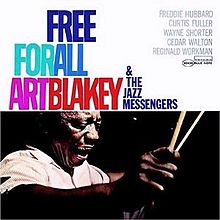

Roomie, a trombonist, was a full time student, something that always surprised me. He formed a sextet for ensemble class. I was lucky to get an invite. We played Jazz Messengers tunes from “Free for All” and “Mosaic”. Even their background parts required bend-your-knees effort. Our rhythm  section swung with a force that reached escape velocity. A whole semester passed and it never once felt like school. We had a little gig in the local club that hydrogen bonded our chemistry.

section swung with a force that reached escape velocity. A whole semester passed and it never once felt like school. We had a little gig in the local club that hydrogen bonded our chemistry.

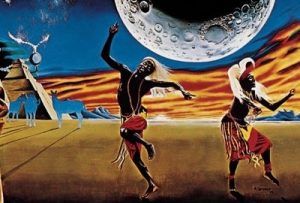

Next semester, on to the Mwandishi Sextet. In listening sessions, Herbie’s music oozed through our speakers. We were mesmerized by the wide open spaces and masterful development across an  entire LP side. It was Ezra Pound’s challenge: make it new. Our final exam, a concert with classmates, a half-dozen bands playing 20 minute sets. In attendance, the new department head, a guy from the suburbs, presenting as a NYC cat. Club date pianist, competent arranger, he hit the jackpot as conductor of the nation’s top college big band.

entire LP side. It was Ezra Pound’s challenge: make it new. Our final exam, a concert with classmates, a half-dozen bands playing 20 minute sets. In attendance, the new department head, a guy from the suburbs, presenting as a NYC cat. Club date pianist, competent arranger, he hit the jackpot as conductor of the nation’s top college big band.

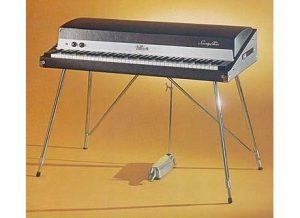

They put us last on the concert. We made our mission plain dragging the ring-modulated Rhodes  from stage left. After, all the cool kids knew we won the conceptual space race. One tune had a totally grooving nineteen beat cycle. Dave, our pianist had taken that ostinato to another galaxy and back.

from stage left. After, all the cool kids knew we won the conceptual space race. One tune had a totally grooving nineteen beat cycle. Dave, our pianist had taken that ostinato to another galaxy and back.

The department head got up, a tall guy, affecting a John Wayne walk. He Duked in front of us and addressed the audience, maybe one hundred-fifty students.

“This reminds me of a porno movie. You wanna know why? Because they took something beautiful and tender and made it obscene and crude. Don’t get me wrong, they all can play. That’s not the issue. See, Herbie played standards. He knows harmony. He wanted to make some money. He deserves to get rich, he really does. But this kind of music is crap. I’m sorry. You’ll have to do much better if you want to stay in this school.”

We all stayed in that school. Dave didn’t get around much anymore, though. He was always in demand for gigs and picky about pianos. The pulverized mechanisms and calliope tuning of most school instruments frustrated him. An exception, the recital hall Steinway grand. Dave signed it out for a “chamber music” rehearsal. He got a time slot and key for the hall. On a day with no scheduled classes, we showed up with horns and bass and did what we always did. About 45 minutes in, a man appeared in our midst. When we didn’t immediately cease playing, he shouted “STOP”. We did.

The Dean of the music school had a Gallic first name. He wore corduroy or tweed jackets with elbow pads. In the halls, he could have been any professor or administrator. His distinguishing characteristic was skin tone. An unknown disease turned him purplish-red. His deeply tanned face, a ruddy blood blister; thick-knuckled hands, a matched pair of extra-large lobster claws.

His flesh may have masked his fury. His voice did not.

“How did you get in here?

Dave: “ I have the room signed out”

“Signed out? Who gave you the ok?”

“Candy, in the office, she…”

“She gave you the ok for…?”

“Chamber music”

“This isn’t chamber music”

“Yes, it is. It..”

“What is your name?”

Dean went around the horn, asking names. He struggled to remain calm, calculating our transgressions as he questioned.

“Come to my office…now”

Before we left the room, he lifted an empty soda can off the piano.

“That’s not ours” Dave said.

The dean looked at him pityingly, replaced the stick, then closed the top. As his hand fell from the lid, he caressed the piano case, eyes following its curve.

We walked through deserted halls, hauling hastily packed instruments, passing through the empty reception area, to enter his office. He rifled through his desk for paper work to report, expel, or just scare us. Dean married a local woman. Her grown son was already a star, playing in a much lauded edition of the school band, with Woody Herman and then Bill Evans’ trio. We sat facing him, gaping at photos of his stepson on stage with legends, framed proclamations and Latinized sheepskins.

“That piano is reserved for departmental recitals. I take it you weren’t rehearsing for a recital.”

“No one plays that piano…”

“My concern is that you lied to get the piano. Then you had a jam session in the recital hall.” He said jam session as if it were murder.

“What’s the purpose of having an instrument, if no one plays it?

“There are pianos in all the practice buildings. You can play there anytime.”

While parrying Dave, he took all our names again, asking spellings, writing with a fancy pen in one of his claws.

“Dean, those instruments are in terrible shape. Actions are a mess, and they’re never tuned.”

“Our tuner is very good and he’s always here. I’m sure he could accommodate you.”

None of us could stop staring at his hands. The creases on his knuckles appeared inked in; hairs sprouting around them, arachnid legs.

“I don’t see why we can’t use the piano, no one else is”

I wouldn’t know Dave was gay until years later. Right now, his bitchy queen worked the room.

“Because, we have rules and we expect everyone to follow them. If you can’t follow rules, maybe you don’t belong in school.”

Nothing came of our heresy. Most of the department’s revenue came from Jazz majors paying out-of-state tuition. At forty bucks a credit, Texas residents could buy a semester of classes for the price of a discount week in Vegas, gaming not included. Non-residents paid five times more. Money ruled, as ever.

The other guys eventually received degrees, probably with an onstage purple handshake. Dave got a six-nighter in Reunion tower, a joint we called “Top of the Dallas Phallus”.  After some road gigs, he returned to Houston. A local business man, newly and fabulously rich, offered him a record deal. Dave hired the Dean’s stepson for two of the dates, knocking his socks off and ironing in the irony.

After some road gigs, he returned to Houston. A local business man, newly and fabulously rich, offered him a record deal. Dave hired the Dean’s stepson for two of the dates, knocking his socks off and ironing in the irony.