by Joshua Wilbur

In college, I took a course on American poetry, but I missed the class on Robert Frost. To be honest, I slept straight through it. That particular winter was brutally cold. I lived in a worn-out house some fifteen minutes from campus, and the water heater in the basement was broken. So I skipped the ice-cold shower at 8AM, the wet walk through a foot of snow, and the monotone reading of a few representative poems by a long-tenured professor. I stayed in my warm bed, wrapped up in the comforter.

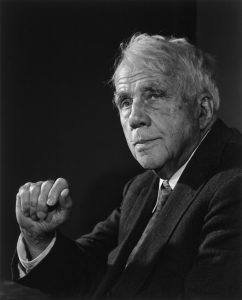

From that morning until only a few weeks ago, my mental image of Robert Frost was that of a grey-haired, folksy New Englander who wrote modest poems about country life. I knew “The Road Not Taken,” though I didn’t understand it. I was familiar with a handful of other titles— “Fire and Ice,” “Mending Wall,” “Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening”— but I can’t say if I had ever really read these poems. If so, they hardly made an impression on me. In short, I had Frost figured as a quaint poet of nature, a leftover from 19th Century America.

I now realize that I was wonderfully mistaken, that Robert Frost isn’t what he seems, and that the fundamental experience of reading Frost is discovering that the poems aren’t what they seem. Harold Bloom has called Frost a “trickster and a mischief maker.” In The New Yorker, Joshua Rothman describes Frost’s “poetic sleight of hand,” his characteristic tendency for deception. In his own words, Frost considered poetry “the one permissible way of saying one thing and meaning another.” For nearly fifty years, the poet hid ulterior meanings behind plain language.

But I didn’t know about any of this as a sleepy undergraduate. I didn’t feel the stimulating effect of Frost’s literary gamesmanship until this past November. I was flipping through a collection of poems edited by Seamus Heaney and Ted Hughes—major poets themselves—called The Rattlebag. I should mention that I don’t often flip through collections of poems. Poetry isn’t a part of my daily routine, and I’m weak on the technicals, especially when it comes to the metrical buffet of iambs, anapests, spondees, trochees, and dactyls. In other words, I’m an occasional, general reader of poetry, someone who enjoys the form without particular aims. This is why I own a copy of Heaney’s and Hughe’s Rattlebag, a diverse assortment of short poems arranged alphabetically and intended for serendipitous discovery. On a quiet weeknight, I sat on the couch, muted the television (which showed a stern Anderson Cooper on CNN), and opened the anthology to “D,” where I cursorily read the following poem:

Desert Places

Snow falling and night falling fast, oh, fast

In a field I looked into going past,

And the ground almost covered smooth in snow,

But a few weeds and stubble showing last.

The woods around it have it–it is theirs.

All animals are smothered in their lairs.

I am too absent-spirited to count;

The loneliness includes me unawares.

And lonely as it is that loneliness

Will be more lonely ere it will be less–

A blanker whiteness of benighted snow

With no expression, nothing to express.

They cannot scare me with their empty spaces

Between stars–on stars where no human race is.

I have it in me so much nearer home

To scare myself with my own desert places.

Immediately, I liked the sound of the poem, its brooding atmosphere. I read it again, twice over, three times. Bruce Springsteen once described his reaction to hearing Bob Dylan’s “Like A Rolling Stone” for the first time: “That snare shot sounded like somebody’d kicked open the door to your mind.” I felt something similar reading this poem—a sudden, visceral appreciation.

Then I noticed the poet’s name in small caps, appearing (in a clever editorial decision by Heaney and Hughes) after the poem itself. “ROBERT FROST.”

I was surprised. “Desert Places” didn’t match my vision of the poet as a “genial, homespun New England rustic,” as Brad Leithauser describes the Frost stereotype. “Desert Places” is downright sinister, more heavy metal than folk, while at the same time conveying a noble stoicism. The poem is complicated, in other words, and, in my ignorance, I didn’t expect such crafty inventiveness from the Poet Laureate of Vermont.

I wanted to learn more—to see how wrong I had been about the Bard of New England. I went to my desk, turned on the monitor, and looked up “Desert Places” on the excellent “Modern American Poetry Site” (MAPS), which features critical interpretations of American poetry. Scrolling through the commentary, my sense of Frost and his poetic universe continued to widen. “I am not a nature poet,” Frost once said in an interview, “All my poems have got a person in them.” In the case of “Desert Places,” the speaker is initially frightened by nature, utterly separated from the woods, the weeds, the animals, and the “benighted snow with no expression, nothing to express.”

Frank Lentricchia of Duke University writes of the poet-speaker: “Probably no poem of Frost’s so well accommodates the wide emotive swings of self which may be probed from early on in his career. In “Desert Places” we watch the speaker go to the brink in his projection; then he comes back to normality, withdraws from dark vision, and rests in the stability of a balanced ironic consciousness. As well as any poem of dark vision that he wrote, ‘Desert Places’ gives evidence of Frost’s ability to achieve aesthetic detachment from certain sorts of destructive experience.”

Another critic argues: “‘Desert Places’…vividly demonstrates the power of the imagination to influence the traveler’s perception of the region he observes.” Frost offers a cold, Western spin on that old piece of yogi wisdom: the world is as you are.

Then there’s that final line. Here are Seamus Heaney’s impressions:

“Consider, for example, the conclusion of ‘Desert Places,’ which I have just quoted: ‘I have it in me so much nearer home / To scare myself with my own desert places.’ However these lines may incline toward patness, whatever risk they run of making the speaker seem to congratulate himself too easily as an initiate of darkness, superior to the deluded common crowd, whatever trace they contain of knowingness that mars other poems by Frost, they still succeed convincingly. They overcome one’s incipient misgivings and subsume them into the larger, more impersonal, and undeniable emotional occurrence which the whole poem represents.”

“Desert Places,” then, culminates in a cool, stoic victory. According to Albert J. von Frank, “The poem restores him to himself, equips him with a sense of who and where he is, defined positively this time, in relation to nature and to the objects to which he will give meaning poetically. […] He can locate “home” because, for the first time in the poem, he can see that there is something in him which does not exist elsewhere, and that “something” is the potential to create meaning.”

Reading these interpretations enriched my understanding of Frost’s wider project, which is to explore the territory between the inner self and the outer world. This grand literary theme is at the heart of all experience, and, for Frost, the dichotomy is best negotiated through artistic expression. In a short essay entitled “The Figure a Poem Makes,” Frost suggests that a poem provide “a momentary stay against confusion.” He continues: “Every poem is an epitome of the great predicament; a figure of the will braving alien entanglements.”

Confronted with chaos, faced with the “confusion” of “alien entanglements,” Frost counters with poetic form. And he does so, to quote Marianne Moore, “in plain American which cats and dogs can read.” This plainness—the apparent simplicity of Frost— is an integral part of his defense against disorder. As Clive James nicely puts it in an article for Prospect Magazine, “Frost worked the miracle of disguising the complicated as the elementary.”

For weeks, I’ve lugged around a copy of Frost’s Collected Poems, and I’ve now encountered his “disguising of the complicated as the elementary” in dozens of unvarnished lyrics. What strikes me about reading Frost today is that so much of contemporary life works the other way around: we attempt to pry basic truths from a dizzying field of complexity. It is difficult for me to read or watch the news, for example, without wondering if we aren’t collectively missing the point, if there aren’t simpler and worthier principles hidden underneath the accumulated layers of culture.

To begin with what’s known and work outwards, as Frost does, is a refreshing alternative to scattered understanding. There is great force in the self-containment of Frost’s lyric poems, each one an island universe to be explored and thought through. Consider “Neither Out Far Nor In Deep,” a beach tour in four stanzas:

Neither Out Far Nor In Deep

The people along the sand

All turn and look one way.

They turn their back on the land.

They look at the sea all day.

As long as it takes to pass

A ship keeps raising its hull;

The wetter ground like glass

Reflects a standing gull.

The land may vary more;

But wherever the truth may be—

The water comes ashore,

And the people look at the sea.

They cannot look out far.

They cannot look in deep.

But when was that ever a bar

To any watch they keep?

I read “Neither Out Far Nor In Deep” on a crowded train. This is practically nothing, I thought, looking up at the people around me and back down to the page. “First of all, of course, the poem is simply there, in indifferent unchanging actuality,” wrote Randall Jarrell, one of Frost’s foremost supporters. Take stock of what’s here: the people, the sand, the gull, the ship, the sea. And what happens? The people look at the sea, though they cannot look out far and they cannot look in deep. That’s all.

What is this poem about then? I was puzzled as the subway car rumbled back and forth: something about our search for meaning. (Frost, I’ve quickly learned, doesn’t pull punches). According to Peter D. Poland, “Frost’s cryptic little lyric ‘Neither Out Far nor In Deep’ remains as elusive as ‘the truth’ that is so relentlessly pursued in the poem itself.”

Mordecai Marcus, who has written an excellent volume that includes commentary on every poem Frost wrote, provides a helpful summary:

“The people turn from the varying sights of land towards the distances of water, representing mysteries they hope to grasp, though the water may not really possess any more such truth than does the land. But the people continue to prefer this attempt at further vision, just as they do at the poem’s opening. Despite their determination and persistence, they cannot achieve a penetrating vision of reality—nature and human nature—or what lies behind it. But they will not stop looking. In the last two lines, the speaker calmly withdraws, balancing admiration and skepticism, glad to see human speculation continuing but confident that it will not achieve much. The poem has been seen as a harsh commentary on human limitations.”

The poet tells us the truth at the same time as he interrogates our search for it. For this, Randall Jarrell congratulates Frost: “This recognition of the essential limitations of man, without denial or protest or rhetoric or palliation, is very rare and very valuable, and rather usual in Frost’s best poetry.”

I’ve wondered about this poem off and on since reading it. I take Frost to be saying that people will be sitting on beaches and gazing out at oceans until the end of time. Some critics seem to think that Frost holds the people in contempt, but I believe he’s among them, staring out himself. If the poet is different, it’s because of what Jarrell recognizes as “very rare and very valuable.” Frost faces up to the facts: he knows his own nature.

Following Frost’s death in 1963, John F. Kennedy delivered a eulogy for the poet at Amherst College, where a groundbreaking ceremony for the Robert Frost Library was being held. It was October; the president would be killed a month later.

Kennedy long admired Frost, asking the poet to read at his inauguration. (Frost famously deviated from reading a poem he’d written for the occasion and instead recited “The Gift Outright” from memory). Nearly two years later, Kennedy spoke wonderfully of Frost’s artistic courage:

“Our national strength matters; but the spirit which informs and controls our strength matters just as much. This was the special significance of Robert Frost.

He brought an unsparing instinct for reality to bear on the platitudes and pieties of society. His sense of the human tragedy fortified him against self-deception and easy consolation.

‘I have been,’ he wrote, ‘one acquainted with the night.’ And because he knew the midnight as well as the high noon, because he understood the ordeal as well as the triumph of the human spirit, he gave his age strength with which to overcome despair.

At bottom, he held a deep faith in the spirit of man. And it is hardly an accident that Robert Frost coupled poetry and power, for he saw poetry as the means of saving power from itself.

When power leads man toward arrogance, poetry reminds him of his limitations. When power narrows the areas of man’s concern, poetry reminds him of the richness and diversity of his existence. When power corrupts, poetry cleanses, for art establishes the basic human truths which must serve as the touchstone of our judgment. The artist, however faithful to his personal vision of reality, becomes the last champion of the individual mind and sensibility against an intrusive society and an officious state. The great artist is thus a solitary figure. He has, as Frost said, ‘a lover’s quarrel with the world.’ In pursuing his perceptions of reality he must often sail against the currents of his time. This is not a popular role. If Robert Frost was much honored during his lifetime, it was because a good many preferred to ignore his darker truths. Yet in retrospect, we see how the artist’s fidelity has strengthened the fiber of our national life…”

This is a poignant speech. It captures what’s drawn me to Frost over these recent weeks, and it makes me hopeful that poetry can still speak to power. In the midst of political turmoil and technological sprawl, it’s easy to lose sight of our more basic condition. Frost sees it because he’s strange enough and bold enough to stare into the midnight woods.

“Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening” was written in 1922, yet it remains powerful today. For me, the poem reads as an exhortation to roll out of bed, to look far and deep, and to go for many miles in search of wherever the truth may be.

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound’s the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.