by Huw Price

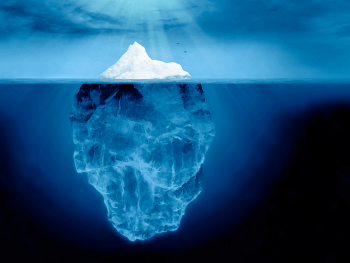

From aviation to zoo-keeping, there’s a simple rule for safety in potentially hazardous pursuits. Always keep an eye on the ways that things could go badly wrong, even if they seem unlikely. The more disastrous a potential failure, the more improbable it needs to be before we can safely ignore it. Think icebergs and frozen O-rings. History is full of examples of the costs of getting this wrong.

From aviation to zoo-keeping, there’s a simple rule for safety in potentially hazardous pursuits. Always keep an eye on the ways that things could go badly wrong, even if they seem unlikely. The more disastrous a potential failure, the more improbable it needs to be before we can safely ignore it. Think icebergs and frozen O-rings. History is full of examples of the costs of getting this wrong.

Sometimes the disaster is missing something good, not meeting something bad. For hungry sailors, missing a passing island can be just as deadly as hitting an iceberg. So the same principle of prudence applies. The more we need something, the more important it is to explore places we might find it, even if they seem improbable.

We desperately need some new alternatives to fossil fuels. To meet growing demands for energy, with some chance of avoiding catastrophic climate change, the world needs what Bill Gates called an energy miracle – a new carbon-free source of energy, from some unexpected direction. In this case it’s obvious what the principle of prudence tells us. We should keep a sharp eye out, even in unlikely corners.

Yet there’s one possibility that has been in plain sight for thirty years, but remains resolutely ignored by mainstream science. It is so-called cold fusion, or LENR (for Low Energy Nuclear Reactions). Cold fusion was made famous, or some would say infamous, by the work of Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons. At a press conference on March 23, 1989, Fleischmann and Pons claimed that they had detect excess heat at levels far above anything attributable to chemical processes, in experiments involving the metal palladium, loaded with hydrogen. They concluded that it must be caused by a nuclear process – ‘cold fusion’, as they termed it. Read more »

The man for whom the word “Emergency” must have been invented (“serious, unexpected, and often dangerous situation requiring immediate action”) pulled the pin out of yet another hand grenade.

The man for whom the word “Emergency” must have been invented (“serious, unexpected, and often dangerous situation requiring immediate action”) pulled the pin out of yet another hand grenade.

I’d been living in Tokyo about ten years, when a friend’s father decided to perform a little experiment on me. Arriving one cool autumn evening at their home in suburban Mejirodai, he waved my friend away, telling her: “I want to have a little chat with Leanne.” Sitting down on the sofa across from him, he poured me a cup of tea. In truth, I can’t recall what we chatted about, but about twenty minutes into the conversation, he suddenly clasped his hand together in delight–with what could only be described as a childlike gleam in his eyes– and said, “Don’t you hear something?”

I’d been living in Tokyo about ten years, when a friend’s father decided to perform a little experiment on me. Arriving one cool autumn evening at their home in suburban Mejirodai, he waved my friend away, telling her: “I want to have a little chat with Leanne.” Sitting down on the sofa across from him, he poured me a cup of tea. In truth, I can’t recall what we chatted about, but about twenty minutes into the conversation, he suddenly clasped his hand together in delight–with what could only be described as a childlike gleam in his eyes– and said, “Don’t you hear something?”

Just about everyone who visits the famous

Just about everyone who visits the famous

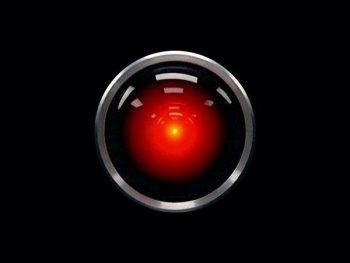

My seventy-something year old uncle, who still uses a flip phone, was talking to me a while ago about self-driving cars. He was adamant that he didn’t want to put his fate in the hands of a computer, he didn’t trust them. My question to him was “but you trust other people in cars?” Because self-driving cars don’t have to be 100% accurate, they just have to be better than people, and they already are. People get drunk, they get tired, they’re distracted, they’re looking down at their phones. Computers won’t do any of those things. And yet my uncle couldn’t be persuaded. He fundamentally doesn’t trust computers. And of course, he’s not alone. More and more of our lives have highly automated elements to them,

My seventy-something year old uncle, who still uses a flip phone, was talking to me a while ago about self-driving cars. He was adamant that he didn’t want to put his fate in the hands of a computer, he didn’t trust them. My question to him was “but you trust other people in cars?” Because self-driving cars don’t have to be 100% accurate, they just have to be better than people, and they already are. People get drunk, they get tired, they’re distracted, they’re looking down at their phones. Computers won’t do any of those things. And yet my uncle couldn’t be persuaded. He fundamentally doesn’t trust computers. And of course, he’s not alone. More and more of our lives have highly automated elements to them,  The Anna Karenina Fix

The Anna Karenina Fix

In the Third Essay of On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche levels a powerful attack on the modern Platonistic conception of mind and nature, urging us to reject such “contradictory concepts” as “knowledge in itself,” or the idea of “an eye turned in no particular direction, in which the active and interpreting forces, through which alone seeing becomes seeing something, are supposed to be lacking.” More recently, Donald Davidson’s attack on the dualism of conceptual scheme and empirical content, and thus of belief and meaning, requires us to see inquiry into how things are as essentially interpretative.

In the Third Essay of On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche levels a powerful attack on the modern Platonistic conception of mind and nature, urging us to reject such “contradictory concepts” as “knowledge in itself,” or the idea of “an eye turned in no particular direction, in which the active and interpreting forces, through which alone seeing becomes seeing something, are supposed to be lacking.” More recently, Donald Davidson’s attack on the dualism of conceptual scheme and empirical content, and thus of belief and meaning, requires us to see inquiry into how things are as essentially interpretative. Andrea Scrima: As a visual artist, I worked in the area of text installation for many years, in other words, I filled entire rooms with lines of text that carried across walls and corners and wrapped around windows and doors. In the beginning, for the exhibitions Through the Bullethole (Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha), I walk along a narrow path (American Academy in Rome) and it’s as though, you see, it’s as though I no longer knew… (Künstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin in cooperation with the Galerie Mittelstrasse, Potsdam), I painted the letters by hand, not in the form of handwriting, but in Times Italic. Over time, as the texts grew longer and the setup periods shorter, I began using adhesive letters, for instance at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Kunsthaus Dresden, the museumsakademie berlin, and the Museum für Neue Kunst Freiburg. Many of the texts were site-specific, that is, written for existing spaces, and often in conjunction with objects or photographs. Sometimes it was important that a certain sentence end at a light switch on a wall, that the knob itself concluded the sentence, like a kind of period. I was interested in the architecture of a space and in choreographing the viewer’s movements within it: what happens when a wall of text is too long and the letters too pale to read the entire text block from the distance it would require to encompass it as a whole—what if the viewer had to stride up and down the wall? And if this back and forth, this pacing found its thematic equivalent in the text?

Andrea Scrima: As a visual artist, I worked in the area of text installation for many years, in other words, I filled entire rooms with lines of text that carried across walls and corners and wrapped around windows and doors. In the beginning, for the exhibitions Through the Bullethole (Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha), I walk along a narrow path (American Academy in Rome) and it’s as though, you see, it’s as though I no longer knew… (Künstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin in cooperation with the Galerie Mittelstrasse, Potsdam), I painted the letters by hand, not in the form of handwriting, but in Times Italic. Over time, as the texts grew longer and the setup periods shorter, I began using adhesive letters, for instance at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Kunsthaus Dresden, the museumsakademie berlin, and the Museum für Neue Kunst Freiburg. Many of the texts were site-specific, that is, written for existing spaces, and often in conjunction with objects or photographs. Sometimes it was important that a certain sentence end at a light switch on a wall, that the knob itself concluded the sentence, like a kind of period. I was interested in the architecture of a space and in choreographing the viewer’s movements within it: what happens when a wall of text is too long and the letters too pale to read the entire text block from the distance it would require to encompass it as a whole—what if the viewer had to stride up and down the wall? And if this back and forth, this pacing found its thematic equivalent in the text?  “[T]here is in fact nothing that can alleviate that fatal flaw in Darwinism” says Professor Behe,

“[T]here is in fact nothing that can alleviate that fatal flaw in Darwinism” says Professor Behe,  rapture, claiming that “Michael Behe’s Darwin Devolves Topples Foundational Claim of Evolutionary Theory” and that “Anyone interested in knowing the truth about the design/evolution debate will find Darwin Devolves a must read.”

rapture, claiming that “Michael Behe’s Darwin Devolves Topples Foundational Claim of Evolutionary Theory” and that “Anyone interested in knowing the truth about the design/evolution debate will find Darwin Devolves a must read.” I wonder whether Behe’s most vociferous supporters actually understand his position. Unlike them, he

I wonder whether Behe’s most vociferous supporters actually understand his position. Unlike them, he