by Samia Altaf

In May 2014, a young man beat his twenty-year-old sister, Farzana, to death by hitting her head with a brick. He did this in broad daylight just outside the High Court building in Lahore, the cultural, artistic and academic capital of Pakistan. He did it as local policemen and passersby looked on, lawyers in their black flowing robes went in and out of their offices and barely fifty yards away, inside the building, the bewigged and begowned Chief Justice sat with his hand on the polished gavel.

In May 2014, a young man beat his twenty-year-old sister, Farzana, to death by hitting her head with a brick. He did this in broad daylight just outside the High Court building in Lahore, the cultural, artistic and academic capital of Pakistan. He did it as local policemen and passersby looked on, lawyers in their black flowing robes went in and out of their offices and barely fifty yards away, inside the building, the bewigged and begowned Chief Justice sat with his hand on the polished gavel.

Farzana, a young woman from a lower-middle-class family, had married a man against her family’s wishes. She had come to the High Court that day to provide proof that she had married voluntarily and had not been abducted by her husband as her family claimed when they filed the case to “get her back.” Farzana was dead, the bridal henna still bright red on her hands and feet, before her case was called for hearing by the court.

Though this was one in a string of incidents of violence against women, and though many similar incidents have happened in Pakistan since, the shock and horror of the murder consumed us for a few days and became international news. On May 29, 2014, the BBC asked, “How can families do this?”

One answer to the question is that families can perpetrate violence against their daughters because they have years of practice doing so every day. Women in Pakistan live in a culture of ambient violence, and incidents of exaggerated violence labeled “honor killings” are just lamentable spikes in the ambient violence of their everyday lives. Read more »

You shouldn’t curse. People will take you less seriously. Cursing also reveals a certain laziness on your part, suggesting that you can’t be bothered to come up with more descriptive language. In the end, when you curse, you short change both yourself and your audience. Instead, take the time to use the language more fully, more carefully, and more artfully. In so doing, your message will be clearer, more forceful, and better received.

You shouldn’t curse. People will take you less seriously. Cursing also reveals a certain laziness on your part, suggesting that you can’t be bothered to come up with more descriptive language. In the end, when you curse, you short change both yourself and your audience. Instead, take the time to use the language more fully, more carefully, and more artfully. In so doing, your message will be clearer, more forceful, and better received.

This is Longyearbyen, Svalbard, Norway, eight hundred miles from the North Pole. Our destination, across the island, is a Russian settlement called Barentsburg.

This is Longyearbyen, Svalbard, Norway, eight hundred miles from the North Pole. Our destination, across the island, is a Russian settlement called Barentsburg.

A.S.: Liesl, I love the part in your story where a pack of kids is playing “Murder in the Dark” and the young narrator’s crush, who plays the part of the killer, draws near her in the dark yard: “I didn’t try to back away, I thought maybe he was going to kiss me, but then he killed me which was so predictable.”

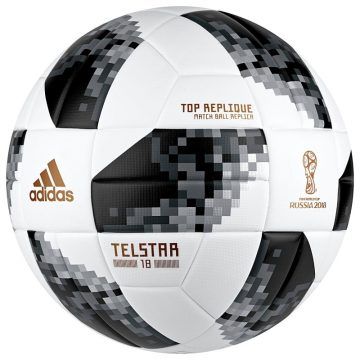

A.S.: Liesl, I love the part in your story where a pack of kids is playing “Murder in the Dark” and the young narrator’s crush, who plays the part of the killer, draws near her in the dark yard: “I didn’t try to back away, I thought maybe he was going to kiss me, but then he killed me which was so predictable.” Now in this damp, stiff swollen fingers, mine, once slender, of gossamer touch, which pierced skin with steel, silk, molded spheres, to be kicked by heroes, turned warriors, turned champions, turned angels in distant lands, on green fields and roaring theaters of fierce contest of fury and cheer. Yet I am not there, at the game, but I am present, in every single game. They don’t know do they, that without me, the game would not be, that without me, they, howling with joy, howling in expectant yowls and cheers awash in victorious and defeated tears, and beer, this ritualistic collective catharsis, all of this, without me, would not happen, would not be. This story. Where am I in it? What is history but unspeakable violence, erasure and invisibility, spat and polished into and put a sheen upon, to create a mirror for those who look. Yes, a mirror, after all that effort to put a spin on it, we can’t get away can we from ourselves? Won’t we all in trying to cross drown in our collective grief? It is I, bobbing in steel on these shores, not allowed in, who’s fingers bloodied by a thousand pierces, who’s eyes blinded by constant attention who brings them this. These intricate delicate, fine, exquisite fingers, this attentive keen sight, this laboring, I bring them this, the very thing they claim as their soul a distilled meaning and morphing to something sublime. I who they bar from entering. I, who has been left un-reading, unread, now thirsty, hungry, suffocating. I who makes all of this. I who am their constant dread. Left for dead. But I am here, here, off shore, there in that field, in that theater, amidst the squeals of joy. No, the game does not happen without me. And now, hidden here, bobbing, stealing away in steel, floating, lurching on waves upon waves, broken away from that bondage of needles and stretching skin for a perfect sphere for kicking, I am here. A prisoner of contained fates. The Adriatic laps outside: the smell of salt, octopus, fir, citrus and jasmine presents itself in the way of salvation in the way of pain, unforgettable almost impossible to conjure in language, in memory, how to give words to the scent of lavender and black pine and Crni bor. Or those left behind. Equally uncontained perfumed keys unlocking the mind. No, the game doesn’t happen without the likes of me. But I am suffocating now, I am contained here in a coffin of steel, upon the sea, unwanted, unwelcomed, unseen, listening to the cheering roar of a crowd ecstatic as some adored gladiator whips it into net—that sphere of skin I have sewn. The game, I cannot enter, does not happen without me.

Now in this damp, stiff swollen fingers, mine, once slender, of gossamer touch, which pierced skin with steel, silk, molded spheres, to be kicked by heroes, turned warriors, turned champions, turned angels in distant lands, on green fields and roaring theaters of fierce contest of fury and cheer. Yet I am not there, at the game, but I am present, in every single game. They don’t know do they, that without me, the game would not be, that without me, they, howling with joy, howling in expectant yowls and cheers awash in victorious and defeated tears, and beer, this ritualistic collective catharsis, all of this, without me, would not happen, would not be. This story. Where am I in it? What is history but unspeakable violence, erasure and invisibility, spat and polished into and put a sheen upon, to create a mirror for those who look. Yes, a mirror, after all that effort to put a spin on it, we can’t get away can we from ourselves? Won’t we all in trying to cross drown in our collective grief? It is I, bobbing in steel on these shores, not allowed in, who’s fingers bloodied by a thousand pierces, who’s eyes blinded by constant attention who brings them this. These intricate delicate, fine, exquisite fingers, this attentive keen sight, this laboring, I bring them this, the very thing they claim as their soul a distilled meaning and morphing to something sublime. I who they bar from entering. I, who has been left un-reading, unread, now thirsty, hungry, suffocating. I who makes all of this. I who am their constant dread. Left for dead. But I am here, here, off shore, there in that field, in that theater, amidst the squeals of joy. No, the game does not happen without me. And now, hidden here, bobbing, stealing away in steel, floating, lurching on waves upon waves, broken away from that bondage of needles and stretching skin for a perfect sphere for kicking, I am here. A prisoner of contained fates. The Adriatic laps outside: the smell of salt, octopus, fir, citrus and jasmine presents itself in the way of salvation in the way of pain, unforgettable almost impossible to conjure in language, in memory, how to give words to the scent of lavender and black pine and Crni bor. Or those left behind. Equally uncontained perfumed keys unlocking the mind. No, the game doesn’t happen without the likes of me. But I am suffocating now, I am contained here in a coffin of steel, upon the sea, unwanted, unwelcomed, unseen, listening to the cheering roar of a crowd ecstatic as some adored gladiator whips it into net—that sphere of skin I have sewn. The game, I cannot enter, does not happen without me.

community, which he found, and a decade later founded the Second Vermont Republic, which advocated Vermont secession from the USA to become an independent state, which it had been from 1777 to 1791. Time magazine named the Second Vermont Republic as one of the “Top 10 Aspiring Nations” in the world as recently as 2011.

community, which he found, and a decade later founded the Second Vermont Republic, which advocated Vermont secession from the USA to become an independent state, which it had been from 1777 to 1791. Time magazine named the Second Vermont Republic as one of the “Top 10 Aspiring Nations” in the world as recently as 2011.

All this is spelt out in Morris’s 1977 book, The Beginning of the World, most recently reprinted in 2005 (in Morris’s lifetime, and presumably with his approval), and available from Amazon as a paperback or on Kindle.

All this is spelt out in Morris’s 1977 book, The Beginning of the World, most recently reprinted in 2005 (in Morris’s lifetime, and presumably with his approval), and available from Amazon as a paperback or on Kindle.

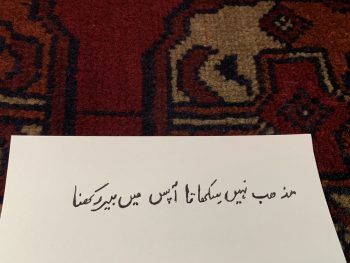

Less than a month ago, the Indian Air Force conducted airstrikes inside Pakistan. The last attack of this kind took place in 1971, before I was born, and though tensions between the two countries have never ceased, even the family’s fragmented recollections of blackouts, travel restrictions and patriotic songs on the radio had become a distant memory for me until the moment I found myself stranded in Karachi due to airspace closure and witnessed not just military crossfire but that of the media of the two countries. The outbursts on news channels, as well as social media were interspersed with slogans and songs. One Indian patriotic song in particular, a ghazal by Allama Iqbal who is known as Pakistan’s national poet, sung not only in the voices of India’s celebrity singers and sweet-faced schoolchildren, but also adapted to their military march tune, caught my attention.

Less than a month ago, the Indian Air Force conducted airstrikes inside Pakistan. The last attack of this kind took place in 1971, before I was born, and though tensions between the two countries have never ceased, even the family’s fragmented recollections of blackouts, travel restrictions and patriotic songs on the radio had become a distant memory for me until the moment I found myself stranded in Karachi due to airspace closure and witnessed not just military crossfire but that of the media of the two countries. The outbursts on news channels, as well as social media were interspersed with slogans and songs. One Indian patriotic song in particular, a ghazal by Allama Iqbal who is known as Pakistan’s national poet, sung not only in the voices of India’s celebrity singers and sweet-faced schoolchildren, but also adapted to their military march tune, caught my attention.