by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

Less than a month ago, the Indian Air Force conducted airstrikes inside Pakistan. The last attack of this kind took place in 1971, before I was born, and though tensions between the two countries have never ceased, even the family’s fragmented recollections of blackouts, travel restrictions and patriotic songs on the radio had become a distant memory for me until the moment I found myself stranded in Karachi due to airspace closure and witnessed not just military crossfire but that of the media of the two countries. The outbursts on news channels, as well as social media were interspersed with slogans and songs. One Indian patriotic song in particular, a ghazal by Allama Iqbal who is known as Pakistan’s national poet, sung not only in the voices of India’s celebrity singers and sweet-faced schoolchildren, but also adapted to their military march tune, caught my attention.

Less than a month ago, the Indian Air Force conducted airstrikes inside Pakistan. The last attack of this kind took place in 1971, before I was born, and though tensions between the two countries have never ceased, even the family’s fragmented recollections of blackouts, travel restrictions and patriotic songs on the radio had become a distant memory for me until the moment I found myself stranded in Karachi due to airspace closure and witnessed not just military crossfire but that of the media of the two countries. The outbursts on news channels, as well as social media were interspersed with slogans and songs. One Indian patriotic song in particular, a ghazal by Allama Iqbal who is known as Pakistan’s national poet, sung not only in the voices of India’s celebrity singers and sweet-faced schoolchildren, but also adapted to their military march tune, caught my attention.

As in other places and other times of conflict, it was clear that words may serve not only as symbols of sovereignty and to cement the bond of nationhood, but can become veritable weapons aimed at the enemy. The media’s language of posturing and propaganda, all too familiar in both countries, saw a marked shift in Pakistan due to the tone set by Prime Minister Khan. In his critically-timed address to the nation, he was neither glib nor incendiary; his sentiments about the loss of life in the Pulwama bombing (claimed by a terrorist group in Pakistan) were heartfelt and expressed at length, his words were measured, dignified, and backed by a genuine spirit of peace. In contrast, the election-fevered Indian premier Modi’s yelling matches continued, as did his media’s angry sloganeering.

Only a few days prior to this, I had given a book talk at Faiz Ghar, (the home of poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz, now a museum) and remarked that conflict and violence leave us too broken for words, and yet, the right words are urgently needed. The context was the aftermath of ’71 and Faiz’s ghazal “Dhaka say wapsi par” as a unique feat of diplomacy. Later, as part of a panel at the Lahore Literary Festival, I spoke about the Kashmiri-American poet Agha Shahid Ali’s use of the English ghazal to bridge the longing for his beloved Kashmir. In the days following the latest military engagement, another ghazal emerged from the cacophony of news and slogans: Iqbal’s ghazal, “Tarana e Hindi” (“Anthem of India”), likely the first one I read as a child (before I knew what a ghazal was) in the collection Baang e Dara.

The history of this ghazal is full of ironies. It was presented by a very young Iqbal, only 24 years of age, at Government College Lahore— really his debut as a poet—and instantly became the anthem of the movement for independence in British India, chanted in rallies, embellishing speeches of leaders, even said to have been recited ‘a hundred times’ by Gandhi in prison. It has remained one of the best loved patriotic songs of India, 72 years since independence.

Ghazal “Tarana e Hindi,” praises the land and people of India, using some of the classical tropes and diction of Urdu poetry, inherited from the Arabo-Persian tradition, such as imagery related to gardens and caravans. Appearing first in the monthly publication “Ittehad” (“Unity” in Urdu) run by Indian freedom activists, the poem electrified the movement by imbuing a sense of unity and pride among countrymen who had gone through centuries of economic exploitation, capitalizing on the “divide and conquer” strategy of the Raj, a regime which had wrested the subcontinent from the Mughals, reducing one of the richest countries of the world to one of the poorest. In historian Will Durant’s words: “The British conquest of India was the invasion and destruction of a high civilization by a trading company utterly without scruple or principle (….) bribing and murdering, annexing and stealing, and beginning that career of illegal and legal plunder.”

It was from the debris of plunder that freedom movements arose around the turn of the century and were gaining momentum as Iqbal came to the scene as a poet. But the author of the song that gave India its first popular sense of selfhood, its first vision as a nation, was to go through further growth and transformation, and ultimately conclude, after his years of education in Europe, that the dream of a free India alone was futile. As was the case with several other Muslim figures of the freedom movement, he grew disenchanted when Hindu loyalties were tested in the climate of the first world war when domestic tensions arose and Iqbal foresaw a very challenging future for Muslims in a united India. During his time abroad, Iqbal gained insights not only into Western philosophy and its development of political ideals, but also came to see Islam through a larger, more complex, dynamic prism, experiencing selfhood as a Muslim, not an Indian, influenced by many Western thinkers but first and foremost by the poetry of Rumi, a figure he considered his spiritual father. Indeed, the earliest translations of Iqbal’s poetry into English were produced by the same two British scholars, Nicholson and Arberry, known for translating not only Rumi and other Sufi poets but also the Quran.

While pursuing a law degree in England and a PhD in Germany, Iqbal had the opportunity of interacting with intellectuals from around the world, including the many Muslim countries under Western colonial rule. He engaged with topics of Western philosophy, history and political theory, but also Islamic mysticism and literature which gave him a new direction and eventually shaped his “two-nation theory,” an idea that would begin the Pakistan movement and come to fruition nine years after his death. Iqbal wrote another ghazal, “tarana e milli” (“Anthem of the Nation”), a different song of selfhood, one that praised Muslims for their faith and civilizational accomplishments; the tone, however was the same as the earlier ghazal: a passionate song to boost the morale of a broken people.

It is tempting to surmise that Iqbal’s idea of India’s division was an extension of the British tendency to encourage political and cultural division or that the study of Islam shaped an exclusivist attitude in Iqbal. The more one embraces the breadth and depth of his poetry, the more one finds that neither of these assumptions could be true, or else his earlier ghazal “Tarana e Hindi” would’ve reflected it, penned as it was at a time when he hadn’t yet gained full maturity, the influences of his study of the Quran and Persian literature, as well as his mentor Mathew Arnold, were the strongest. Rumi’s poetry and Rumi’s interpretation of the Quran surpassed any other influence on Iqbal, and the vision of a sovereign state where Muslims could practice their faith freely and in peace, became his final mission.

Independence and partition took a colossal toll on the Indian subcontinent, resulting in the horrors of death, destruction and displacement we have yet to overcome. Being part of a family that was divided and displaced, time and again I have ruminated over the partition and participated in discussions on whether it was worthwhile to create boundaries where there had been none. The sad truth is that whether there are physical boundaries or not, divisions may still exist. Neither India nor Pakistan has been able to create a society that allows its citizens the equality and freedom envisioned by the founding fathers and promised by the earliest establishments. Both countries continue to be in the clutches of divisive rhetoric and religion-based violence; in the case of the present Indian government, such violence and inequality are backed by institutions purported to be secular. The following verse from Iqbal’s ghazal comes to mind:

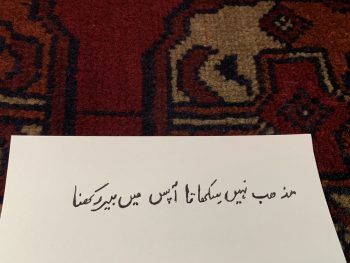

Mazhab naheen sikhata aapus mein baer rakhna

Hindi hain hum, watan hai sara jahan hamara