by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

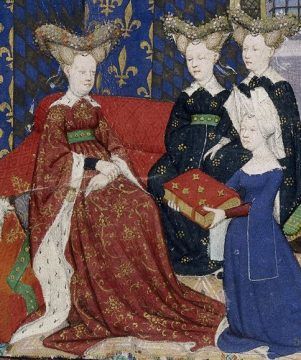

The year was 1683. And the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire, Kara Mustafa Pasha, was leading one of the most organized war machines the world had ever seen, westward– toward Vienna. We know that his campaign would end in failure. The Pasha himself held ultimately responsible, he would be made to suffer the punishment of death by strangulation. The skin of his head peeled off and stuffed with straw, this gruesome “head” was then delivered to the Sultan back in Constantinople in a velvet bag.

Make sure you tie the knot right, he reportedly said with great bravado to his executioners as they prepared to tie the silken cord around his neck.

Only imagine how optimistic he must have been months earlier as he led his powerful army toward the city known to the Ottomans as the “Golden Apple.” Before the battle, Kara Mustafa had sent an official demand for surrender of the city. It was pure formality– as both sides knew this was to be a fight to the finish.

The Ottomans, for their part, had already set up camp and began digging.

Digging?

The walls of Vienna were famous back then. Built during the 13th century using ransom money from the high-profile kidnapping of King Richard the Lionhearted (who had made the mistake of getting captured near Vienna whilst traveling home from the Holy Land), these walls had proved an impossible challenge the last time the Ottomans had come to town, in 1529. That was under Suleiman the Magnificent. And it wasn’t just the walls that challenged the invading army; for surrounding the walls were massive fortifications –including projecting bastions, ravelins, and ramparts. The entire city was then further fortified by wide artificial slopes (the glacis). That is why the best chance the Ottomans had was to dig under the bastions and detonate explosives to bring the fortifications down. Read more »

In 1974, noted science fiction author Joe Haldeman published a novel called The Forever War, which won several awards and spawned sequels, a comic version, and even a board game. The Forever War tells the story of William Mandella, a young physics student drafted into a war that humans are waging against an alien race called the Taurans. The Taurans are thousands of light years away, and traveling there and back at light speed leads Mandella and other soldiers to experience time differently. During two years of battle, decades pass by on Earth. Consequently, the world Mandella returns to each time is increasingly different and foreign to him. He eventually finds his home planet’s culture unrecognizable; even English has changed to the point that he can no longer understand it.

In 1974, noted science fiction author Joe Haldeman published a novel called The Forever War, which won several awards and spawned sequels, a comic version, and even a board game. The Forever War tells the story of William Mandella, a young physics student drafted into a war that humans are waging against an alien race called the Taurans. The Taurans are thousands of light years away, and traveling there and back at light speed leads Mandella and other soldiers to experience time differently. During two years of battle, decades pass by on Earth. Consequently, the world Mandella returns to each time is increasingly different and foreign to him. He eventually finds his home planet’s culture unrecognizable; even English has changed to the point that he can no longer understand it.

Madeleine LaRue: It did turn out to be pretty mammoth! How about I tell you, by way of introduction, about the first time I met Bichsel in person. He’d come to read at the Literarisches Colloquium in Berlin, the center of the grand old West Berlin literary establishment. It was November, it was dark and cold, and when he emerged at the back of the room and started walking up toward the stage, wearing the same black leather vest he’s been wearing for the past forty years, I think we were all a little worried about him. He was eighty-two then, and he looked exhausted. It had been a while since he’d been on such an extensive reading tour outside of Switzerland. He got to the stage and settled into his chair. The moderator welcomed him and asked how it felt to be back in Berlin—a simple question, a nice, easy opener. Bichsel still seemed tired, but as he leaned back and said, very slowly, in his lilting Swiss accent, “Ja, ja, Berlin,” his eyes lit up and he launched into a story about his first time in the city, in the early 1960s, and how he got caught in the middle of a bar fight with some people! Who turned out to be Swiss! And they all got thrown out onto the street together, and he’ll never forget it! And ja, ja, Berlin—and from his very first word, we all became like delighted children at Grandfather’s feet, totally enraptured, utterly unwilling to go to bed until we’d heard just one more story, pleeeease? And he himself became younger, full of life, charming and hilarious and genuine and profound.

Madeleine LaRue: It did turn out to be pretty mammoth! How about I tell you, by way of introduction, about the first time I met Bichsel in person. He’d come to read at the Literarisches Colloquium in Berlin, the center of the grand old West Berlin literary establishment. It was November, it was dark and cold, and when he emerged at the back of the room and started walking up toward the stage, wearing the same black leather vest he’s been wearing for the past forty years, I think we were all a little worried about him. He was eighty-two then, and he looked exhausted. It had been a while since he’d been on such an extensive reading tour outside of Switzerland. He got to the stage and settled into his chair. The moderator welcomed him and asked how it felt to be back in Berlin—a simple question, a nice, easy opener. Bichsel still seemed tired, but as he leaned back and said, very slowly, in his lilting Swiss accent, “Ja, ja, Berlin,” his eyes lit up and he launched into a story about his first time in the city, in the early 1960s, and how he got caught in the middle of a bar fight with some people! Who turned out to be Swiss! And they all got thrown out onto the street together, and he’ll never forget it! And ja, ja, Berlin—and from his very first word, we all became like delighted children at Grandfather’s feet, totally enraptured, utterly unwilling to go to bed until we’d heard just one more story, pleeeease? And he himself became younger, full of life, charming and hilarious and genuine and profound.  Having before you an iced mango

Having before you an iced mango

I don’t know anything about music. I make art, and like many artists I listen to music while working. Nearly every kind of music, but mostly metal for those time-to-get-serious moments. Atmospheric black metal with little discernible speech tends to work best, because it provides a setting such that one can become lost in the droning distortions when working on something. The music I like to hear is that which Kant would endorse as sublime – enormous walls of sound that result in a distractedness where one can go undeterred by outside forces. Of course an fMRI could show what is happening in the brain, what psychically galvanizes me while I listen to music in those moments, but I’m less interested in what’s happening to me as much as what’s happening to it: what happens to artworks when produced to a soundtrack?

I don’t know anything about music. I make art, and like many artists I listen to music while working. Nearly every kind of music, but mostly metal for those time-to-get-serious moments. Atmospheric black metal with little discernible speech tends to work best, because it provides a setting such that one can become lost in the droning distortions when working on something. The music I like to hear is that which Kant would endorse as sublime – enormous walls of sound that result in a distractedness where one can go undeterred by outside forces. Of course an fMRI could show what is happening in the brain, what psychically galvanizes me while I listen to music in those moments, but I’m less interested in what’s happening to me as much as what’s happening to it: what happens to artworks when produced to a soundtrack?