by Joseph D. Martin and Marta Halina

Calls for a Manhattan Project–style crash effort to develop artificial intelligence (AI) technology are thick on the ground these days. Oren Etzioni, the CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, recently issued such a call on The Hill. The analogy is commonly used to describe DeepMind’s initiative to build artificial general intelligence (AGI). It is similarly used to describe military initiatives to build AGI. At a conference last year, DARPA announced a $2 billion investment in AI over the next five years. Ron Brachman, former director of DARPA’s cognitive systems initiative, said at this conference that a Manhattan Project is likely needed to “create an AI system that has the competence of a three-year old.”

Calls for a Manhattan Project–style crash effort to develop artificial intelligence (AI) technology are thick on the ground these days. Oren Etzioni, the CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, recently issued such a call on The Hill. The analogy is commonly used to describe DeepMind’s initiative to build artificial general intelligence (AGI). It is similarly used to describe military initiatives to build AGI. At a conference last year, DARPA announced a $2 billion investment in AI over the next five years. Ron Brachman, former director of DARPA’s cognitive systems initiative, said at this conference that a Manhattan Project is likely needed to “create an AI system that has the competence of a three-year old.”

In one sense, the goals of such analogies are clear. AI, the comparison implies, has the potential to be as transformative for our society as nuclear weapons were in the mid-twentieth century. Whoever masters it first will enjoy a massive head start on the next wave of technological development, economic competition, and, yes, the arms race of the twenty-first century. It’s a project that comes with ethical implications that demand focused and well-resourced attention. These consequences are so important that we should not bat an eye at ploughing limitless resources into its development.

But if this analogy is to sustain such a bold claim, it bears closer scrutiny. First, analogies of this sort are not innocuous. Invocations of historical examples, especially examples so iconic as the Manhattan Project or the Apollo program, aim to borrow the authority—and implications of success—that such historical episodes command. It is prudent to examine analogies to see if that authority is merited, or if it has been unjustly swiped. Read more »

Fans are the people who know the quotes, the dates of publication, the batting averages, the bassist on this album, the team that general manager coached before. I am not a fan. Don’t get me wrong. I’m full of enthusiasms. But I can’t match you statistic for statistic. I haven’t read the major author’s minor novel. I don’t care who the bassist was. You win. I’m an amateur.

Fans are the people who know the quotes, the dates of publication, the batting averages, the bassist on this album, the team that general manager coached before. I am not a fan. Don’t get me wrong. I’m full of enthusiasms. But I can’t match you statistic for statistic. I haven’t read the major author’s minor novel. I don’t care who the bassist was. You win. I’m an amateur. When I watched the 2019 documentary on Apollo 11, it carried me back not to the summer of 1969, when it happened, but to the mid-1980s, when I was an undergrad. I was eight when Apollo 11 launched; of course I was aware of the space program and the moon landings, but I don’t have any memories of everyone gathering around to watch those first steps on another world. My parents weren’t particularly interested, and I don’t remember being caught by the spirit of the times myself.

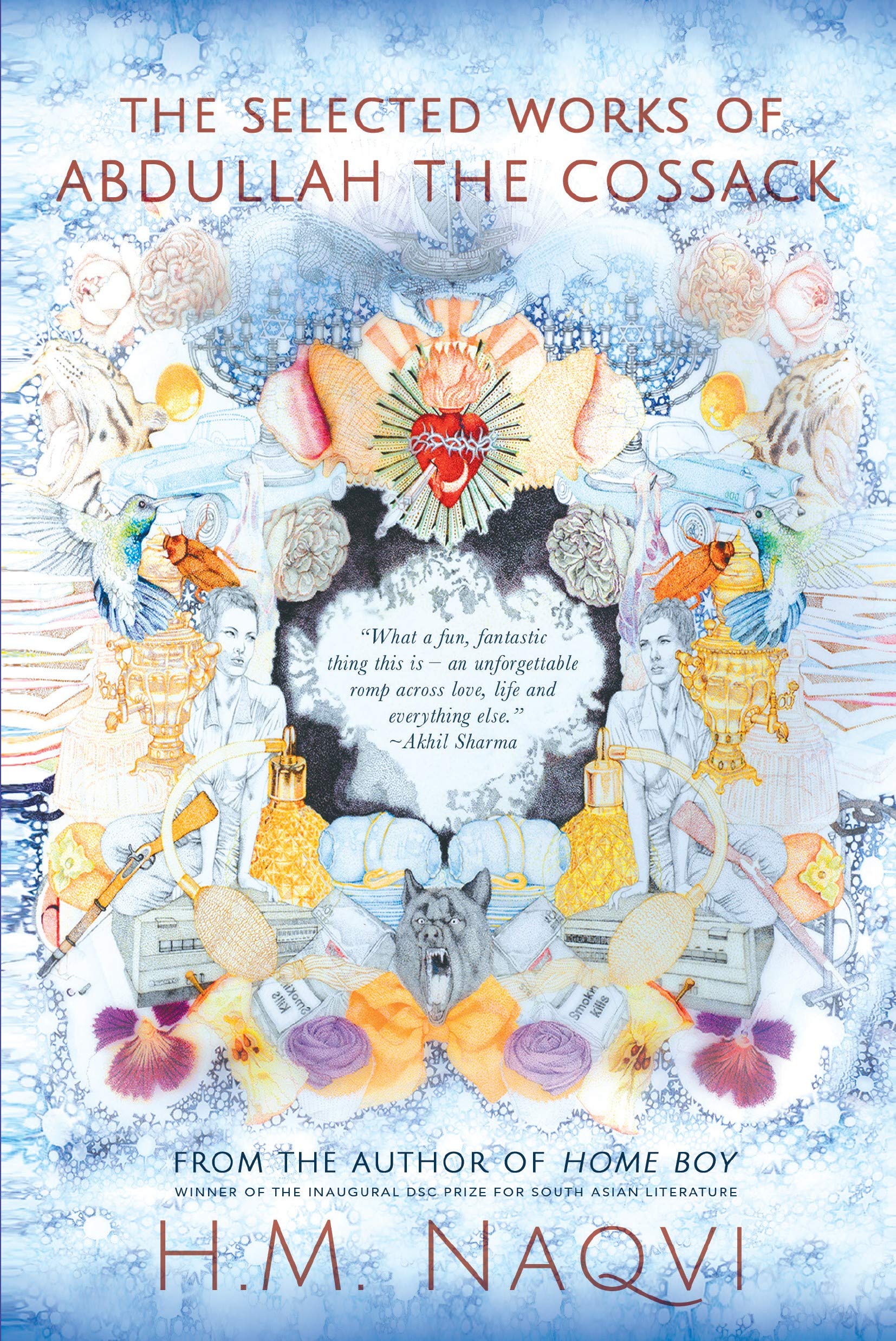

When I watched the 2019 documentary on Apollo 11, it carried me back not to the summer of 1969, when it happened, but to the mid-1980s, when I was an undergrad. I was eight when Apollo 11 launched; of course I was aware of the space program and the moon landings, but I don’t have any memories of everyone gathering around to watch those first steps on another world. My parents weren’t particularly interested, and I don’t remember being caught by the spirit of the times myself. cinematic representations of Muslims. Stage One features stereotyped figures (the taxi driver, terrorist, cornershop owner, or oppressed woman). Stage Two involves a portrayal that subverts and challenges those stereotypes. Finally, Stage Three is ‘the Promised Land, where you play a character whose story is not intrinsically linked to his race’. Does

cinematic representations of Muslims. Stage One features stereotyped figures (the taxi driver, terrorist, cornershop owner, or oppressed woman). Stage Two involves a portrayal that subverts and challenges those stereotypes. Finally, Stage Three is ‘the Promised Land, where you play a character whose story is not intrinsically linked to his race’. Does

Our expectations sculpt neural activity, causing our brains to represent the outcomes of our actions as we expect them to unfold. This is consistent with a growing psychological literature suggesting that our experience of our actions is biased towards what we expect. —

Our expectations sculpt neural activity, causing our brains to represent the outcomes of our actions as we expect them to unfold. This is consistent with a growing psychological literature suggesting that our experience of our actions is biased towards what we expect. — Into the Woods

Into the Woods

My friend does not use punctuation when he texts, so there is a stream-of-consciousness quality to much of his communications. According to the fine folks at

My friend does not use punctuation when he texts, so there is a stream-of-consciousness quality to much of his communications. According to the fine folks at

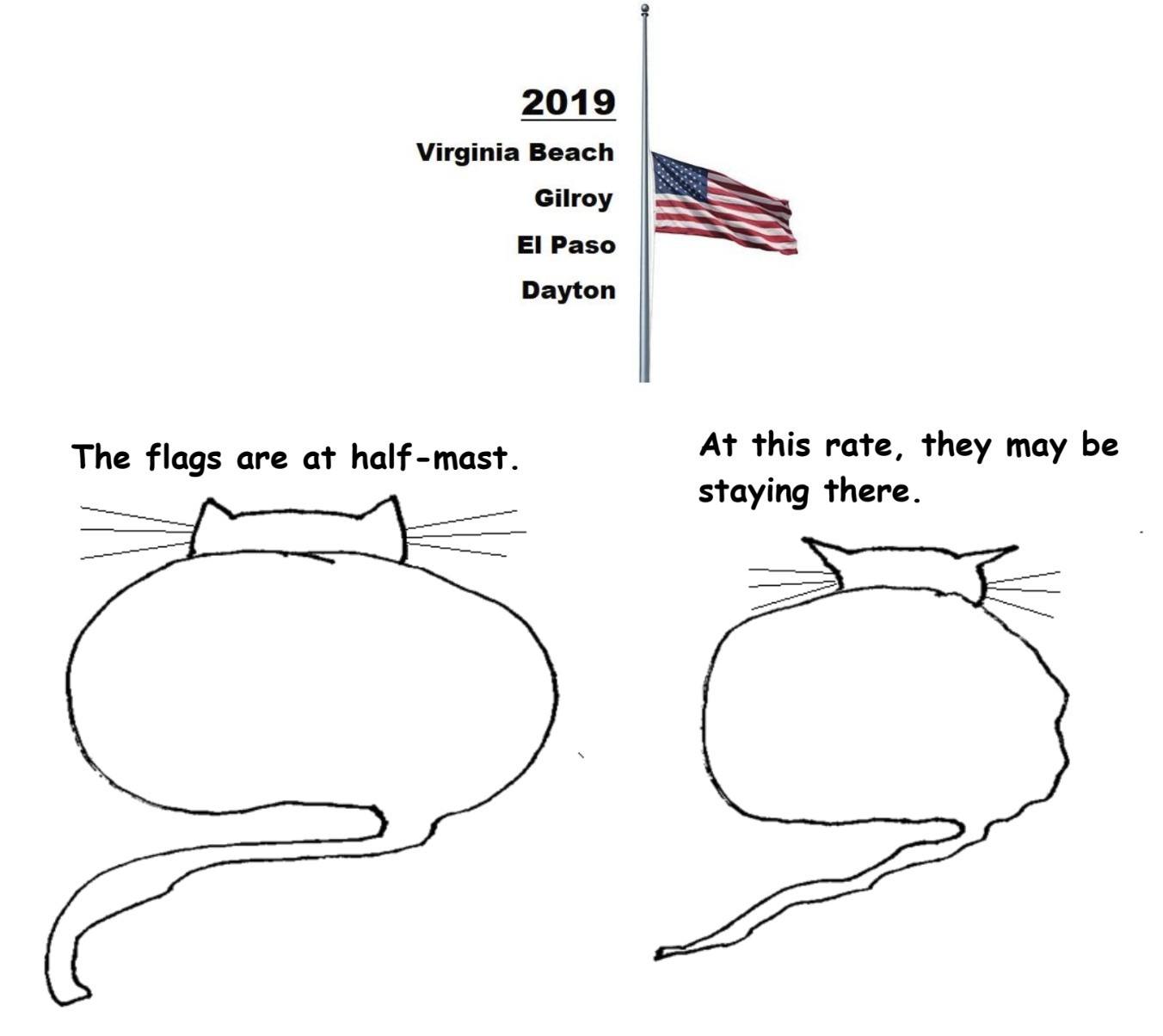

The right to own guns is typically justified by the fundamental right to self-defense against bad guys, either our fellow citizens or the state itself if it were to turn tyrannical. Both of these have a superficial appeal but fail in obvious ways. Guns are an effective means of defending oneself against bad guys only so long as they don’t have guns too (because being equally armed doesn’t add up a defense against those who can pick and choose their moment of aggression). Civilians with guns are also ineffective against the armies and ruthless terroristic violence of a truly tyrannical regime.

The right to own guns is typically justified by the fundamental right to self-defense against bad guys, either our fellow citizens or the state itself if it were to turn tyrannical. Both of these have a superficial appeal but fail in obvious ways. Guns are an effective means of defending oneself against bad guys only so long as they don’t have guns too (because being equally armed doesn’t add up a defense against those who can pick and choose their moment of aggression). Civilians with guns are also ineffective against the armies and ruthless terroristic violence of a truly tyrannical regime. So goes a popular snippet from Seinfeld. In a 2014 article in The Guardian titled “Smug: The most toxic insult of them all?” Mark Hooper opined that “there can be few more damning labels in modern Britain than ‘smug.'” And CBS journalist Will Rahn declared, in the wake of Donald Trump’s 2016 electoral victory, that “modern journalism’s great moral and intellectual failing [is] its unbearable smugness.”

So goes a popular snippet from Seinfeld. In a 2014 article in The Guardian titled “Smug: The most toxic insult of them all?” Mark Hooper opined that “there can be few more damning labels in modern Britain than ‘smug.'” And CBS journalist Will Rahn declared, in the wake of Donald Trump’s 2016 electoral victory, that “modern journalism’s great moral and intellectual failing [is] its unbearable smugness.”