by Claire Chambers

Today I ask to what extent it is a positive development that there are no discussions of race and religion in Danny Boyle’s and Richard Curtis’s film Yesterday, whose protagonist Jack Malik is from a South Asian, possibly Muslim, background.

In his essay ‘Airports and Auditions’ for Nikesh Shukla’s The Good Immigrant, the actor Riz Ahmed outlined three stages of  cinematic representations of Muslims. Stage One features stereotyped figures (the taxi driver, terrorist, cornershop owner, or oppressed woman). Stage Two involves a portrayal that subverts and challenges those stereotypes. Finally, Stage Three is ‘the Promised Land, where you play a character whose story is not intrinsically linked to his race’. Does Yesterday reach that Promised Land or fall short? I examine the film’s depiction of Jack Malik, whose race and religion are irrelevant to this story about love, fame, the music industry, and the Beatles.

cinematic representations of Muslims. Stage One features stereotyped figures (the taxi driver, terrorist, cornershop owner, or oppressed woman). Stage Two involves a portrayal that subverts and challenges those stereotypes. Finally, Stage Three is ‘the Promised Land, where you play a character whose story is not intrinsically linked to his race’. Does Yesterday reach that Promised Land or fall short? I examine the film’s depiction of Jack Malik, whose race and religion are irrelevant to this story about love, fame, the music industry, and the Beatles.

Building on Riz Ahmed’s work, in 2017 two researchers, Sadia Habib and Shaf Choudry, developed the Riz Test for Muslims’ depictions in film and television. Inspired by Ahmed’s speech to the House of Commons about the power and harm of media representations, Habib and Choudry created their own version of the famous Bechdel Test for cinematic portrayals of women. They asked some key questions about the cinematic portrayals of Muslims:

If the Film/ TV Show stars at least one character who is identifiably Muslim (by ethnicity, language or clothing) – is the character:

- Talking about, the victim of, or the perpetrator of terrorism?

- Presented as irrationally angry?

- Presented as superstitious, culturally backwards or anti-modern?

- Presented as a threat to a Western way of life?

- If the character is male, is he presented as misogynistic? Or if female, is she presented as oppressed by her male counterparts?

If the answer for any of the above is Yes, then the Film/ TV Show fails the test.

This test has already been hugely influential in the world of television, with Channel 4’s new Head of Drama Caroline Hollick (herself of Trinidadian descent, pictured) arguing at 2019’s Bradford Literature Festival that it should be uppermost in the mind of anyone commissioning programmes about Muslims.

Habib’s and Choudry’s work shows that words matter and have power. Cinematic writing is an endeavour that involves the creation of an imaginary world, and in doing so allows viewers to reimagine and remake their physical world. As Ahmed himself said to Parliament, ‘Every time you see yourself in a magazine or on a billboard, TV, film, it’s a message that you matter, that you’re part of the national story, that you’re valued. You feel represented’. Distorted reflections, the actor argued, contribute to alienation and even radicalization. Some stories strip others of their complex humanity. Meanwhile more textured tales, as in Yesterday, reveal them in their humanity and without resorting to the tired tropes identified in the Riz Test. All this is to be commended, and Yesterday without a doubt passes the test.

However, Jack Malik is a very liberal character. He and his parents drink alcohol without it being an issue, and no members of the family express opinions about religion or politics. They are also shown as living a comfortable, though not ostentatious life. The family seem well integrated and viewers are not shown them suffering from any racist or anti-religion prejudice or discrimination. Jack has a multicultural circle of friends and has sex outside of marriage with his white girlfriend Ellie Appleton. Ultimately, the only non-mainstream thing about him is his surname and the colour of his skin. Does this film, therefore, really represent progress in representing difference?

The characters’ ethnicity being only a very minor point of their characterization would be a good thing, as per the Riz Test. However, the film goes even further and entirely erases their culture or religion beyond the surname Malik. This name is carefully chosen for its ambiguity. Maliks are usually Punjabi but can be both Muslims and Hindus. However, the film’s two British Asian male characters have Christian first names (or nicknames): Jack and Jed. Jack’s mother Sheila’s name is more complex, as it is common to Christians and Hindus. This suggests an interesting familial backstory, perhaps involving an interfaith marriage, but it is one that is never explored. I think this is a shame, and if a few cultural markers had been mentioned in a nonchalant way it would have done more for diversity. As it is, the film verges on the erasure of difference.

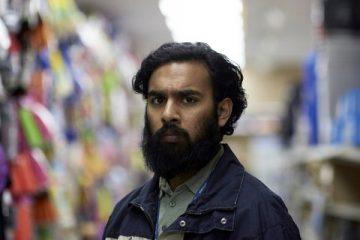

Jack is played brilliantly by the British actor Himesh Patel, himself from an Indian-Kenyan background and known for his work portraying a British Pakistani on the popular soap opera EastEnders. Patel was chosen for the role, which was written  ‘with[out] a specific race in mind’, because he could sing and play guitar as well as being a fine actor. In an interview he speaks movingly about one Indian woman telling him she burst into tears seeing a fellow South Asian in such a part without it being a big deal.

‘with[out] a specific race in mind’, because he could sing and play guitar as well as being a fine actor. In an interview he speaks movingly about one Indian woman telling him she burst into tears seeing a fellow South Asian in such a part without it being a big deal.

I was charmed by Yesterday, with Jack/Patel’s rendition of the Beatles’ ‘Back in the USSR’ in contemporary Russia and several Ed Sheeran jokes as particular highlights. However, I worry that the filmmakers, in trying to satisfy lazy demands for relatability, suppressed any history for the family beyond their present day.

I wonder if one day there will be a Stage Four for Muslims’ celluloid depictions. Is it too much to hope that a funny, loving, and idiosyncratic family member could slip off to pray rather than have a drink without it raising eyebrows? Or are the only good Asians invisible ones who are ‘just like you’, the mainstream audience?