by Emrys Westacott

Elaine: “I hate smugness. Don’t you hate smugness?

Cabdriver, “Smugness is not a good quality.”

So goes a popular snippet from Seinfeld. In a 2014 article in The Guardian titled “Smug: The most toxic insult of them all?” Mark Hooper opined that “there can be few more damning labels in modern Britain than ‘smug.'” And CBS journalist Will Rahn declared, in the wake of Donald Trump’s 2016 electoral victory, that “modern journalism’s great moral and intellectual failing [is] its unbearable smugness.”

So goes a popular snippet from Seinfeld. In a 2014 article in The Guardian titled “Smug: The most toxic insult of them all?” Mark Hooper opined that “there can be few more damning labels in modern Britain than ‘smug.'” And CBS journalist Will Rahn declared, in the wake of Donald Trump’s 2016 electoral victory, that “modern journalism’s great moral and intellectual failing [is] its unbearable smugness.”

But what is smugness? What, exactly, do people find objectionable about it? And is it really such a terrible moral failing, worthy of being described as “unbearable”?

What is smugness?

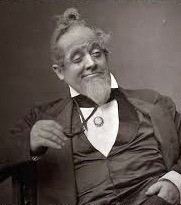

For an immediate graphic example of smugness, just look at a picture of Britain’s new prime minister Boris Johnson smirking in front of 10 Downing Street. For a less stomach-churning way of getting an initial handle on the concept, consider a few concrete instances. Here are four:

- Someone on a very high income says, “Yes, I am well compensated, but I like to think I’ve earned it, and that I’m worth it. As a general rule, I think it’s fair to assume that pay reflects merit.”

- A parent whose children have been admitted to prestigious universities, talking to one whose child is at a less selective college, says, “It’s nice to know that one’s kids will be taught by real experts in the field, and that their classmates will be at their intellectual level.”

- A punter who has won $500 at the race track backing a rank outside can’t help smirking at the crestfallen faces of his friends who all backed the favorite.

- A couple regularly preen themselves on their healthy and ecologically responsible eating habits.

Smugness is not arrogance. Arrogant people typically display a sense of their own importance and superiority with little subtlety: they strut; they are dogmatic; they are dismissive of others. Smugness shares with arrogance a high degree of self-satisfaction and a sense of some kind of superiority over others, but it typically manifests itself quietly and indirectly, without brashness. Muhammad Ali, who called himself “The Greatest,” was undeniably sure about his own superiority as a boxer, and he was called many things–arrogant, loud-mouthed, lippy–but I don’t recall anyone describing him as smug. Read more »