by Joan Harvey

It was inevitable. Michael Pollan’s justly lauded book, How to Change Your Mind, was going to lead straight, sensible, old people to doing drugs. “Today I am a middle-aged journalist working in London, the finance editor of The Economist, a wife, mother, and, to all appearances, a person totally devoid of countercultural tendencies,” writes Helen Joyce in the New York Review of Books, after having gone off to Amsterdam to do a good dose of psilocybin.

And of course all kinds of people are tripping these days. The musician Sudan Archives says she was “doing a lot of psychedelics….I swear to God, when I started to experiment with stuff like that, that’s when I became a little more creative.”

Suzy Batiz, who got extremely rich by developing “Poo-Pouri” (a product I’ve somehow never felt the need to buy) mentions that she has done 94 ayahuasca ceremonies to date. From her ayahusasca experiences she has decided she’s a “business shaman.” Yikes! Has it come to this already?

These nice people are having the usual ecstatic experiences that somehow can be expressed only in cliché. “It is possible to feel differently about things,” the journalist writes. “You don’t have to be who you’ve always been. More things are choices than you imagined. Ordinary things are very beautiful if you’ve the eyes to see.”

Don’t get me wrong. I’m all for this. And I doubt I could write about psychedelic experiences in any particularly interesting way. But in my neck of the woods, the mountains above Boulder, inhabited by an odd mix of outsiders, the children of outsiders, and occasional outsider college professors, I’m pretty sure the percentage of those who have done acid and other psychedelics is far higher than the national (or for that matter global) norm. It is not unusual to be at weddings here in which a decent percentage of the people are in various altered states. The most astonishing aspect of Pollan’s book for many of us was that he didn’t trip until he was almost 60. How did he manage, we wonder, to get so far without? Read more »

In 1885 Mary Terhune, a mother and published childcare adviser, ended her instructions on how to give baby a bath with this observation:

In 1885 Mary Terhune, a mother and published childcare adviser, ended her instructions on how to give baby a bath with this observation:

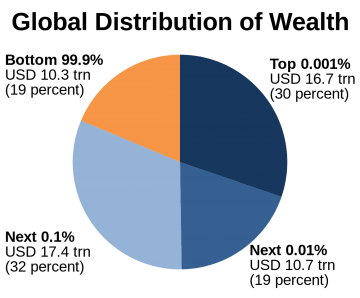

A 2011 survey by Michael Norton and Dan Ariely, of Harvard’s Business School, found that the average American thinks the richest 25% of Americans own 59% of the wealth, while the bottom fifth owns 9%. In fact, the richest 20% own 84% of the wealth, and the bottom 40% controls only 0.3%. An avalanche of studies has since confirmed these basic facts: Americans radically underestimate the amount of wealth inequality that exists – and the level of inequality they think is fair is lower than actual inequality in America probably has ever been. As journalist Chrystia Freeland put it, “Americans actually live in Russia, although they think they live in Sweden. And they would like to live on a kibbutz.”

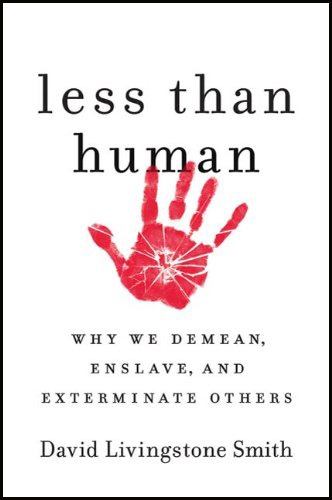

A 2011 survey by Michael Norton and Dan Ariely, of Harvard’s Business School, found that the average American thinks the richest 25% of Americans own 59% of the wealth, while the bottom fifth owns 9%. In fact, the richest 20% own 84% of the wealth, and the bottom 40% controls only 0.3%. An avalanche of studies has since confirmed these basic facts: Americans radically underestimate the amount of wealth inequality that exists – and the level of inequality they think is fair is lower than actual inequality in America probably has ever been. As journalist Chrystia Freeland put it, “Americans actually live in Russia, although they think they live in Sweden. And they would like to live on a kibbutz.” We are all aware that from amongst the vast diversity of life forms that inhabit the earth, human beings are exceptional. But while human beings are capable of inexhaustible creativity and goodness, they also have the potential to commit the most heinous acts and demeaning of fellow human beings. Accounting for such a phenomenon in the human condition and the committing of abominable acts towards their own species, is an issue that perplexes many. Perhaps the answer to such a question can be found by studying the genes or analysing the brain functioning of the perpetrators, but that could involve investigating entire populations who knowingly condone or participate in such acts. A simpler answer could be that human beings have yet to evolve into a species that is incapable of acts of inhumanity. David Livingstone Smith’s book Less than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others offers us insight into the processes that lead to the designating of fellow human beings as ‘subhuman’ and makes possible the potential for human beings to perpetrate acts that can only be considered as evil.

We are all aware that from amongst the vast diversity of life forms that inhabit the earth, human beings are exceptional. But while human beings are capable of inexhaustible creativity and goodness, they also have the potential to commit the most heinous acts and demeaning of fellow human beings. Accounting for such a phenomenon in the human condition and the committing of abominable acts towards their own species, is an issue that perplexes many. Perhaps the answer to such a question can be found by studying the genes or analysing the brain functioning of the perpetrators, but that could involve investigating entire populations who knowingly condone or participate in such acts. A simpler answer could be that human beings have yet to evolve into a species that is incapable of acts of inhumanity. David Livingstone Smith’s book Less than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others offers us insight into the processes that lead to the designating of fellow human beings as ‘subhuman’ and makes possible the potential for human beings to perpetrate acts that can only be considered as evil.

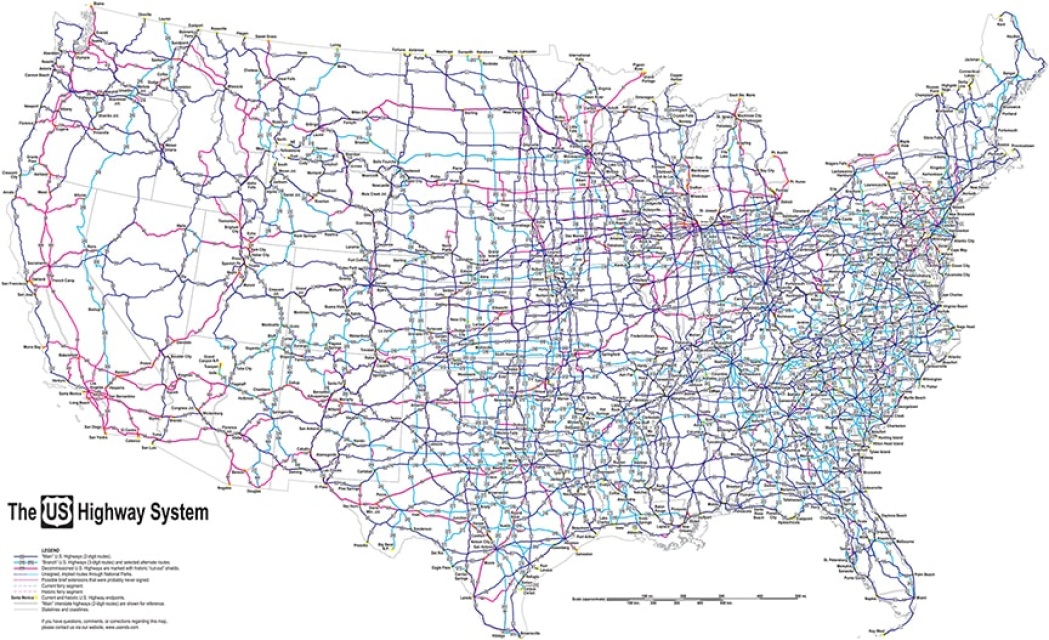

This song got caught in my head as I circled the country in my 1998 Honda. Leaving New York City, I drove west into the heart of America, up to the Dakotas, out to California, down the Golden State, and then back along the Southern route before angling northward to Baltimore. I saw nearly all the America you can see. But of course there’s not just one America. There are many.

This song got caught in my head as I circled the country in my 1998 Honda. Leaving New York City, I drove west into the heart of America, up to the Dakotas, out to California, down the Golden State, and then back along the Southern route before angling northward to Baltimore. I saw nearly all the America you can see. But of course there’s not just one America. There are many.

Eve Sussman and Simon Lee are visual artists who use a variety of media, ranging from photography and film to live performance. Some of their work experiments with narrative tropes in video, text, and the act of talking to other people on the phone or in the real world. Their joint projects include CollusionNoCollusion, created during a residency in St. Petersburg, Russia; No food No money No jewels, commissioned by the Experimental Media and Performing Art Center in Troy, New York; the performance/installation Barbershop; and the live channeling performance … and all the reporters laughed and took pictures. Together they co-founded the Wallabout Oyster Theatre, a micro-theatre run out of their studios in Brooklyn. Sussman and Lee also act as producers for Jack & Leigh Ruby, two reformed criminals who are now making art and films based on their previous career as successful con artists. Recently Sussman and Lee have started working with

Eve Sussman and Simon Lee are visual artists who use a variety of media, ranging from photography and film to live performance. Some of their work experiments with narrative tropes in video, text, and the act of talking to other people on the phone or in the real world. Their joint projects include CollusionNoCollusion, created during a residency in St. Petersburg, Russia; No food No money No jewels, commissioned by the Experimental Media and Performing Art Center in Troy, New York; the performance/installation Barbershop; and the live channeling performance … and all the reporters laughed and took pictures. Together they co-founded the Wallabout Oyster Theatre, a micro-theatre run out of their studios in Brooklyn. Sussman and Lee also act as producers for Jack & Leigh Ruby, two reformed criminals who are now making art and films based on their previous career as successful con artists. Recently Sussman and Lee have started working with

GENIE: AT LAST! Esteemed Master, you have released me from the ancient lamp! Out of my boundless gratitude, I shall grant you three wishes!

GENIE: AT LAST! Esteemed Master, you have released me from the ancient lamp! Out of my boundless gratitude, I shall grant you three wishes!

The indicators that people use to track and understand their moods include exercise, diet, sleep, and many others. I’ve been thinking recently that my library activity surely must be correlated with my mood. I’m a frequent user of two libraries, and my checkouts and returns have a fairly small and regular ebb and flow. Overlying these minor fluctuations are larger and more diffuse patterns that I think offer clues to my inner state.

The indicators that people use to track and understand their moods include exercise, diet, sleep, and many others. I’ve been thinking recently that my library activity surely must be correlated with my mood. I’m a frequent user of two libraries, and my checkouts and returns have a fairly small and regular ebb and flow. Overlying these minor fluctuations are larger and more diffuse patterns that I think offer clues to my inner state.