Trailblazer: From the Mountains of Kashmir to the Summit of Global Business and Beyond

by Rafiq Kathwari

A Jewish grandfather and a Muslim man walk into a New York delicatessen….and 55 years later the Muslim man writes a trailblazing autobiography.

A Jewish grandfather and a Muslim man walk into a New York delicatessen….and 55 years later the Muslim man writes a trailblazing autobiography.

He’s scrawny when he leaves his native home in the Vale of Kashmir, a disputed land in the Himalayan foothills between India and Pakistan. He dodges an impending war. He has no formal passport, just an official residency permit which expired many years ago.

Yet, he takes a chance and, amazingly, boards the last flight from Delhi to Lahore before war breaks out.…it’s an electrifying moment among many, some heartbreaking, some joyful, others human, all too human.

Those moments lead one to believe that the young man was destined for the future of his adopted home, America, where his grit and pluck, his trysts with good luck, his innate belief in common sense all combined to feed his fire within before the fire could feed on him.

Read, how many years ago the Jewish grandfather saw the hunger in the eyes of the Muslim man and sent him on a Mission Impossible to Washington D.C.

Muslim man made the impossible possible, earning the trust of his Jewish mentor who, soon after, handed over the captaincy of his quintessentially Yankee company— Ethan Allen (named after a hero of the American Revolution) — that he had founded during the Great Depression to the young Muslim man named Farooq — which in Islamic tradition means “The Redeemer” or “the one who distinguishes between right and wrong.”

Read how Farooq brought his only previous role as captain (of his college cricket team in his native Kashmir) to bear upon his new captaincy of Ethan Allen in Danbury, Connecticut, its headquarters. Read more »

Stuck, Ch. 7. Bartender Bookmarks: Thin Lizzy, “Rosalie”

Stuck is a weekly serial appearing at 3QD every Monday through early April. The Prologue is here. The table of contents with links to previous chapters is here.

by Akim Reinhardt

During high school, my friends and I used to drink at a local Irish bar. And when I say Irish bar, I don’t mean some contrived yuppie shit hole with an Irish name, a bunch of Gaelic tchochkes splattered across the wall, and overpriced pints of Guiness poured poorly. I mean a working class bar in the Kingsbridge section of The Bronx where Irish immigrants drank, mostly bottles of Bud emptied into small, stemmed glassware. Whatever’s cheap.

The place was called Harper’s. The clientele was mostly old men, with a cacophony of younger people occasionally crowding in on the weekends. Me and my friends started drinking there when we were 16. The legal age in New York was still 18, and neighborhood bars usually didn’t care so long as you were within a couple of years. I didn’t bother buying a fake ID until I went away to college in Michigan. At corner bars in The Bronx, no one even bothered to ask.

Harper’s was the kind of quiet hole in the wall where nothing was happening, but anything could happen and it wouldn’t surprise you. Like out of the blue one night, some guy setup a guitar and small PA, and started singing sad sap Irish folk songs like “I Wish I Was Back Home in Derry.” Harper’s never had live music, but suddenly there he was.

No one paid attention. He never came back.

At some point you were also sure to have someone come into the bar and try to sell you something. Maybe a woman hawking black market movies on VHS, or a huckster pretending to be deaf and mute, collecting money for a fake charity, or some guy peddling roses that you could give to your lady.

None of us ever had a lady. All we ever bought was booze. Read more »

Monday, December 16, 2019

The Disconsolation of Philosophy

by Joseph Shieber

This semester I’ve been teaching a first year seminar entitled “Propaganda”. It is, unfortunately, a very timely topic.

The course draws first year students from across the spectrum of majors — some up-and-coming humanities majors, but also economists, natural scientists and engineers. Because of that mix, and because of the fact that I can’t really expect that many of the students have been exposed to philosophical thinking in their pre-college careers, I try to use the course as an opportunity to introduce the students to a little bit of how philosophy is done.

Having taught the course over a few iterations now, I’ve had an opportunity to observe a few different reactions on the part of my students to the bit of philosophy that we engage in in the course. There’s some dismissiveness, of course, on the part of some of the students, but I’ve also noted surprise on the part of some of the students in response to my own stance about how modest the fruits of philosophy often are.

I think that many of the students expect me to claim more for philosophy and what it can achieve. Perhaps they expect me to declaim dramatically that there is no such thing as truth. Instead, I’m more than happy to assert a variety of truths: that human-caused global warming is a genuine phenomenon, for example, or that vaccines don’t cause autism, or that human beings are the result of evolution by natural selection. But I also take pains to try to expose the assumptions on which those assertions of mine rely. And I also try to trace how different assumptions — including about what counts as good evidence — might lead someone to have different beliefs.

What I hope to achieve with the way that I deploy philosophy in the course is to get students to appreciate the value of intellectual humility. I want them to recognize how rigorous and exacting intellectual humility can be. It involves excavating the hidden premises that underlie our beliefs. It is also compatible with maintaining our belief in the truth of those premises, while at the same time acknowledging that those who accept different, incompatible premises, will arrive at different beliefs. Read more »

Her Father, and Eurydice

by Abigail Akavia

at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

When you opened the door to the apartment where I grew up, you could see all the way to the end of the living room and the large window that spanned its width, an entryway-less structure typical of apartment buildings in Tel Aviv. Our living room was particularly long, though, so that my father’s desk, which sat close to the window but facing the middle of the room, felt far enough away to be considered its own space, set apart from the bustle of a three-kids household that was also my mother’s in-home clinic. Add to the physical distance my father’s ability to immerse himself in whatever he was reading, ignoring anything that was not a direct address to him (one of those universal dad superpowers, my mothering self now knows), and he was almost completely cordoned off from the rest of us when he was sitting at his desk, as if behind a door ajar.

Even when his reading lamp was the only light on in the big room, it was possible to consider his almost immobile figure as not quite there. When my first boyfriend stepped into the apartment for the first time, however, he most definitely recognized my father’s dimly-lit, looming professor-like presence at the edge of the room. He was what you would call “a good kid”—I, in hindsight, have taken to defining him, even at 19, as a mensch—and he took the prospective meeting with my dad seriously. My father, for his part, preferred to act as if nothing out of the ordinary was happening. He put down his glasses, looked up to say a short hello, and then resumed his reading, a combination of simply holding on to his business-as-usual seat at his desk, deliberately extending the gift of privacy to his late-bloomer daughter, and a possibly unconscious urge to avoid the awkwardness of the encounter.

Maybe he also knew, in a parental sixth-sense which I used to think only my mother had but of which I can now also imagine a paternal version, that this very nice guy wasn’t the love of my life—that he was not going to sweep me away, there was really nothing to worry about. So there was no menacing handshake, no steely look into the young man’s eyes to force him to own up to his mythically filthy intentions and metaphorical abduction of my father’s youngest, no once-over to assess his prospective ability to provide for me. In short, no forced and embarrassing macho face-off. Read more »

Perceptions

Martin Roth. “from may to june 2012 i grew grass on rugs in a castle”.

” …This state of in-between is central to his Persian rugs on which grass grows “on the ‘dust of history’.” They were inspired by philosopher Michel Foucault’s examination of “heterotopias,” spaces that both exist and do not exist. Since the designs of carpets were first patterned after gardens, Foucault wrote that “the garden is a rug onto which the whole world comes to enact its symbolic perfection, and the rug is a sort of garden that can move across space.”

Boris Johnson and the worst of times

by Emrys Westacott

“It was the best of times; it was the worst of times.”

I suspect there are many who feel that this Dickensian paradox applies to their own life and times. I certainly do. If you’re fortunate enough to have a sufficient income, a comfortable home, loving family and friends, decent physical and mental health, and plenty of interests to pursue, then life is good. But then a lying, narcissistic, cynical, conman like Boris Johnson is ensconced in power in the UK for five years, and things are not good. One dwells in the Slough of Despond.

I suspect there are many who feel that this Dickensian paradox applies to their own life and times. I certainly do. If you’re fortunate enough to have a sufficient income, a comfortable home, loving family and friends, decent physical and mental health, and plenty of interests to pursue, then life is good. But then a lying, narcissistic, cynical, conman like Boris Johnson is ensconced in power in the UK for five years, and things are not good. One dwells in the Slough of Despond.

This odd disconnect between the relative pleasantness of one’s own circumstances and an appalled sense that, on so many counts (poverty, inequality, political corruption, news media, environmental damage…..), the world is heading in the wrong direction, has become a familiar, ever-present condition for many of us.

Interestingly, the disconnect seems to be not only experienced by people on the left. The median household income of Trump supporters during the 2016 Republican primaries was $72,000 (compared to a national median household income figure of $56,000). Historically and geographically speaking, $72K is a decent chunk of change which for most people should make possible a fairly comfortable lifestyle. And in fact, a 2017 PRRI study concluded that Trump supporters were not so much motivated by dissatisfaction with their own economic circumstances as by fears about cultural displacement (of whites by minorities and immigrants).[1] For most of them, too, their fear, anger, and dissatisfaction concerned the state of the nation rather than their personal circumstances. Read more »

The tyranny of distance: the life of a young Australian chess player

by Cathy Chua

Earlier this year one of the encounters technology has made available for mind games took place – the 2019 Junior Speed Chess Championship. The technology is impressive, with the board, and video commentary by two masters, along with video of the players.

Earlier this year one of the encounters technology has made available for mind games took place – the 2019 Junior Speed Chess Championship. The technology is impressive, with the board, and video commentary by two masters, along with video of the players.

Smirnov, the Australian number one player was outranked by his US counterpart and lost, despite picking up a handy win in the first game. I wondered if it was the usual story of Australia suffering from its location in the world. For Smirnov it was an early morning start, something which chess players normally do anything to avoid. The timing was definitely against him.

If you are Australian, then the expression ‘the tyranny of distance’ has a meaning that has never gone away. The Internet and other technological advances have made the world smaller, but the gains for Australia have always been offset by the fixed disadvantages, which for the foreseeable future will not change.

Perhaps there is a future in which mind sports like chess are strictly fought over virtual boards. But for now the ones that count involve travelling to a point where competitors congregate and push wood, as the expression has it. Casting my memory back to days when I made these trips in the 1970s and 1980s, improvements are apparent for Australians. Read more »

The Cancer Questions Project, Part 20: Ahmet Burhan Ferhanoglu

Dr. Burhan Ferhanoglu is specialized in areas of lymphoma, Hematological Malignancies and multiple myeloma. He is a member of many national and international scientific societies, including the Turkish Hematology Association, American Society of Hematology, European Bone Marrow Transplantation Society and International Society of hematology. In 1998, he became the chief of the Hematology Department of V.K.V American Hospital in Istanbul. Currently, he serves as head of the Department of Internal Medicine at Koç Üniversitesi School of Medicine in Turkey, Istanbul.

Azra Raza, author of The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last, oncologist and professor of medicine at Columbia University, and 3QD editor, decided to speak to more than 20 leading cancer investigators and ask each of them the same five questions listed below. She videotaped the interviews and over the next months we will be posting them here one at a time each Monday. Please keep in mind that Azra and the rest of us at 3QD neither endorse nor oppose any of the answers given by the researchers as part of this project. Their views are their own. One can browse all previous interviews here.

1. We were treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with 7+3 (7 days of the drug cytosine arabinoside and 3 days of daunomycin) in 1977. We are still doing the same in 2019. What is the best way forward to change it by 2028?

2. There are 3.5 million papers on cancer, 135,000 in 2017 alone. There is a staggering disconnect between great scientific insights and translation to improved therapy. What are we doing wrong?

3. The fact that children respond to the same treatment better than adults seems to suggest that the cancer biology is different and also that the host is different. Since most cancers increase with age, even having good therapy may not matter as the host is decrepit. Solution?

4. You have great knowledge and experience in the field. If you were given limitless resources to plan a cure for cancer, what will you do?

5. Offering patients with advanced stage non-curable cancer, palliative but toxic treatments is a service or disservice in the current therapeutic landscape?

Fault Lines

by Tamuira Reid

Mom, why are we always at the doctor? Every week we come here. Are you dying?

Mom, why are we always at the doctor? Every week we come here. Are you dying?

No, baby.

Why are we always here then?

If you grow-up in NYC with a single mom at the helm, then you grow-up in waiting rooms. And every kid knows what waiting rooms really are: babysitters. And they all pretty much look the same. Books with pages missing. Cartoons on a television jutting out of the wall. And if you’re lucky, an entire vat of dum-dums in every flavor known to man.

This is a special kind of doctor. A doctor that takes care of my brain.

Your brain is sick?

Yeah, a little. I guess you could say that.

Like my dad’s?

Not that sick.

I’ve become very good at self-editing. Hiding what needs to be hidden, saying what needs to be said. The fact that there is a rhino-sized pit in my stomach is my business. No one needs to peer into the bowels of my brokenness.

Ollie looks at me through his coke-rimmed glasses, so dirty I can barely see his big green eyes. He’s waiting for more information. I can feel him processing. Read more »

The Punk Archipelago: Postmodern Translocal Consumer Identity

by Mindy Clegg

In issue 85 of The Big Takeover, regular contributor Tim Sommer declared in his editorial that we continue to get punk wrong. Rather than a singular historical event, split between NYC and London, he argued for two different events with a shared name happening in each place.1 He advocates for something like a polygenist theory of punk, which he argues only stabilized in definition in the early 1990s with the popularity of Green Day and the like. There is much to like about his argument, most notably the acknowledgment that people often attempt to shoehorn a neat and tidy narrative onto the past in a way that does little justice to history. Without meaning to perhaps, he mostly points out the divergence between histories written by music critics (often, but not always, in service to the mainstream of the recording industry) and those written by historians seeking to better understand change over time.

The corporate-driven narratives some more mainstream critics produce represents the kind of bad history he’s rebelling against here, histories that assume and anticipate outcomes and progress. In these sorts of historical accounts, the end is already established and all roads lead to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Sommer hovers around that, while not precisely coming out and saying it. After all, he very well knows the problems with the mainstream music industry dominating the narrative. I wish to springboard off Sommer’s insights to highlight a more nuanced view of the history of punk rock, one of the two most important musical movements in the last quarter of the twentieth century (the other being hip hop). Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

Where Is Lahore Going?

by Samia Altaf

When we were young and living in Sialkot, we went frequently, almost once a week, to Lahore, the grand and hip city just a two-hour drive away. The trips were ostensibly for some real work—father, a district court lawyer, was appearing in a case being heard in the High Court or, his tuxedo in the trunk, was heading to a meeting of the Freemasons. Or it was for mother, who had critical shopping at Haji Karim Buksh, for crystal fruit bowls or the latest coffee cups, things not to be found in Sialkot, or was going to Hanif’s for a hair trim. Mother in the early 1960s sported a Jackie Kennedy cut that needed serious maintenance and only Hanif’s could manage that. For the children it might be to see doctors or dentists at Sir Ganga Ram Hospital—deflected septum (one of the boys was an avid boxer), enlarged tonsils, persistent skin rash, and such. And of course the routine checkups for father’s hypertension. Sialkot at the time did not have specialist doctors or reliable surgical facilities. (Interestingly enough it still does not, despite being a manufacturer and exporter of surgical goods.)

When we were young and living in Sialkot, we went frequently, almost once a week, to Lahore, the grand and hip city just a two-hour drive away. The trips were ostensibly for some real work—father, a district court lawyer, was appearing in a case being heard in the High Court or, his tuxedo in the trunk, was heading to a meeting of the Freemasons. Or it was for mother, who had critical shopping at Haji Karim Buksh, for crystal fruit bowls or the latest coffee cups, things not to be found in Sialkot, or was going to Hanif’s for a hair trim. Mother in the early 1960s sported a Jackie Kennedy cut that needed serious maintenance and only Hanif’s could manage that. For the children it might be to see doctors or dentists at Sir Ganga Ram Hospital—deflected septum (one of the boys was an avid boxer), enlarged tonsils, persistent skin rash, and such. And of course the routine checkups for father’s hypertension. Sialkot at the time did not have specialist doctors or reliable surgical facilities. (Interestingly enough it still does not, despite being a manufacturer and exporter of surgical goods.)

SGRH and Fatima Jinnah Medical College for Women were where mother’s sister worked as a young doctor, and where the best doctors were, as far as we were concerned. It was there that we sat on high stools in the college canteen and sipped Coca-Cola on the rocks. Rocks! At a time when ice cubes had barely made their way into our lives. Coca-Cola in tall glasses through paper straws—even the paper straw a novelty, what to say of the nose-tingling fizzy drink. Thrown in would be a visit to grandma for a rest and wash and maybe a sleepover. Grandma lived on Waris Road and in addition to encouraging comments on how one had grown—since last week!—we got to eat oodles of delicious food, homemade mango ice cream in summer and piping hot gajar halwa in winter, and to flirt with the curly-haired shy cousins on holiday from Karachi. Usually an evening trip to the zoo in Lawrence Gardens, named after John Lawrence, one of the viceroys, was a bonus. (Lawrence Gardens has now morphed into Bagh-e-Jinnah.)

But in reality all of these were just excuses to go to Lahore, that grand and glorious city full of throbbing and thrilling life, of sin and splendor, of glamorous women in sleeveless, waistless blouses worn with chiffon saris and men with Brylcreemed hair in bow ties congregating at the Gymkhana Club or Services Club, or the Saturday night jam session at Falleti’s Hotel. Read more »

The Pacific Crest Trail and Its Wild Communities

by Katie Poore

A few weeks ago, one of my closest friends finished a thru-hike of the Pacific Crest Trail, the 2,650-mile footpath that snakes its way from Campo, California on the Mexican border to Mansfield Park, a few miles into Canada. It follows—as the name suggests—the crests of some of the West’s grandest mountain ranges: the Cascades in the Pacific Northwest, the Sierra Nevadas further south. It meanders through the Mojave Desert in southern California.

Ever since I read Cheryl Strayed’s 2012 memoir Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail as a fourteen-year-old, this footpath has occupied something of a sacred space in my imagination. And I am, evidently, not the only one. The trail granted 4,000 long-distance permits in 2016, the majority given to those intending to thru-hike—or walk the entire length of—the trail. Outside Magazine reports that the release of Wild’s 2014 film adaptation resulted in a 300% increase in web traffic on the official PCT website. If you’ve watched Netflix’s new installment of Gilmore Girls, you might recall a few scenes where Lorelai decides to remake her over-complicated life by following in Strayed’s footsteps. As she staggers to the PCT trailhead, however, she is greeted by a hoard of middle-aged divorcées and otherwise unsatisfied women with precisely the same idea. “Book or movie?” they ask each other. Gilmore Girls paints this journey as a kitschy one, the modern woman’s cliché strategy for shrugging off a mid-life crisis and walking off crappy ex-husbands. But here’s what’s true about those women, and the real people who hike this trail: most of them are there to remake themselves, to realize something, even if they don’t know what that something is just yet.

One can believe or not believe in this kind of spiritual journey, but it’s nonetheless an idea whose roots run deep in American soil. Think of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson and John Muir, of Robert Frost and Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman. Consider Annie Dillard. Wendell Berry. Mary Oliver, whom the New York Times calls “one of the best-selling poets in the country.” Narratives of a redemptive natural world are everywhere. American wilderness, it seems, is nothing if not a spiritual and intellectual treasure trove. Where the flora and fauna run wild, these writers suggest, so may our souls. Read more »

Monday Photo

Book Review: Drink More Wine! A Simple Guide to Peak Experiences NOW

by Dwight Furrow

It’s the holiday season and time to think about presents for the budding wine lover in your life. Of course, any season is the right time to think about that. You should always support your local wine lover. One place to begin is this compelling book by long-time food critic Jon Palmer Claridge entitled Drink More Wine! A Simple Guide to Peak Experiences Now. Most books on wine are meant to inform. This book is no exception, but it is also meant to inspire. It performs both tasks admirably and raises a philosophical issue to ponder as well.

It’s the holiday season and time to think about presents for the budding wine lover in your life. Of course, any season is the right time to think about that. You should always support your local wine lover. One place to begin is this compelling book by long-time food critic Jon Palmer Claridge entitled Drink More Wine! A Simple Guide to Peak Experiences Now. Most books on wine are meant to inform. This book is no exception, but it is also meant to inspire. It performs both tasks admirably and raises a philosophical issue to ponder as well.

Claridge delivers essential information about varietals and wine regions in easily digestible, bit-sized morsels along with helpful advice on topics such as how to read a wine label, wine and food pairings, setting up wine tastings, storing and serving wines. He covers just enough grape varietals and regions to pique the interest of people new to wine without weighing things down with too much information. (There are, thankfully, no dissertations on soil types or yeast strains.) He manages an authoritative voice without sounding like a snob and most of this information is disseminated via charming, personal vignettes from his extensive travel and entertainment experiences. Most helpful are his recommendations for wines that are affordable and available at even modestly well-stocked wine stores thus avoiding the common complaint that wine writers focus on wines that ordinary consumers can’t find. His advice about buying budget wine in the supermarket is particularly helpful. (Tip: Beware the bait and switch. Stores will use high scores from one superior vintage to sell that wine from a different vintage). Read more »

Stuck, Ch 6. Nowhere to Run: Bob Seger, “Night Moves”

Stuck is a weekly serial appearing at 3QD every Monday through early April. The Prologue is here. The table of contents with links to previous chapters is here.

by Akim Reinhardt

When a song gets really stuck in my head, I break it down. I learn how to play it and even ponder ways to fiddle with it and improve it. In the throes of involuntary obsession, it gives me something to do. It’s a coping mechanism, a way to retain my sanity. And for this project, it also means writing, at least a little bit, about the song and artist. To create some context.

When a song gets really stuck in my head, I break it down. I learn how to play it and even ponder ways to fiddle with it and improve it. In the throes of involuntary obsession, it gives me something to do. It’s a coping mechanism, a way to retain my sanity. And for this project, it also means writing, at least a little bit, about the song and artist. To create some context.

But I don’t need to talk about “Night Moves,” or any of a dozen other radio staples by Bob Seger. Why? Because Bob Seger is already a part of you, me, and everyone else. Bob Seger has sold over 50,000,000 albums.

Jesus, what kind of figure is that? 50,000,000. Is that a real number? If it does exist, where would I find that number? Somewhere between the Sun and Saturn, I reckon.

But even if you’re not among the many millions who’ve purchased a Bob Seger album during the last 40 years, he is still woven into every American’s existence. Even if you don’t listen to “classic rock,” or you’re a younger person who can’t put his name to his songs, you still know his music. You know Bob Seger even if you don’t know you know Bob Seger. Because if you’ve ever walked down the aisle of a supermarket, loitered in a 7-11, or simply stood there and pumped your gas, then you’ve heard more Bob Seger than you could possibly imagine. He’s had so many successful songs that simply listing them all would be tedious. Read more »

Monday, December 9, 2019

Taking Philosophy into the Field

by Robert Frodeman and Evelyn Brister

People sometimes express confusion about what public philosophy is. We see the point as straightforward: it’s a matter of location. Public philosophy consists of all those efforts that aren’t centered on university life. Public philosophers write op-eds for newspapers, work on disability issues and penal reform, serve on expert committees for government agencies, teach in prisons and schools, and help community groups balance considerations of justice with economic development. But while the possibilities for public philosophy are infinite, the distinction is clear: are your attentions directed toward other philosophers? That’s academic philosophy. Are your efforts aimed at the wider world? That’s public philosophy.

People sometimes express confusion about what public philosophy is. We see the point as straightforward: it’s a matter of location. Public philosophy consists of all those efforts that aren’t centered on university life. Public philosophers write op-eds for newspapers, work on disability issues and penal reform, serve on expert committees for government agencies, teach in prisons and schools, and help community groups balance considerations of justice with economic development. But while the possibilities for public philosophy are infinite, the distinction is clear: are your attentions directed toward other philosophers? That’s academic philosophy. Are your efforts aimed at the wider world? That’s public philosophy.

We’re pluralists in our attitude toward public philosophy: all of these varieties are useful in a world that too often assumes that the answers to societal questions come down to science or economics. But we want to emphasize one particular strain of public philosophy: what we call field philosophy. By analogy with field science, field philosophers work on-site with non-philosophers over an extended period of time. These are philosophers who are not simply writing about public problems but are engaged in projects, working alongside people as they confront real-world issues.

In a recent 3QD piece, Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse sound dubious about the usefulness of public philosophy. They claim that public philosophy has a distressing retrospective quality: by commenting on a situation philosophers are likely to affect that situation, and so are engaged in a continual process of catch-up. We grant the point, but we fail to see it as a problem. Public philosophy does not only consist of external, after-the-fact historical commentary. Particularly in the case of field philosophy, it actively participates in making sense of unfolding cultural events and reveals the conflicting pulls that make for difficult decisions. This iterative loop forms part of the dynamics of thinking, where an account adjusts to changed circumstances. The philosopher thinks with the scientist, the engineer, the businessperson, or the stakeholders’ group. Adjustment in the face of real-world conditions is how things are supposed to work. Read more »

Perceptions

Charles “Teenie” Harris. Girl Reading on Stack of Pittsburgh Courier Newspaper, 1940.

In the current “Truthiness and News” exhibition at DeCordova Museum, Lincoln, MA.

Silver gelatin print.

Truthiness and the News explores the evidentiary role of photography, from the heyday of newsprint in the first half of the twentieth century to the current age of post-truth politics. Presaging the contemporary turn to “alternative facts” and “fake news,” photographs in print journalism have always offered a multiplicity of truths depending on when and how editors chose to print them. Featuring works from the 1940s to the present, this exhibition highlights photojournalists and socially engaged photographers, such as Charles “Teenie” Harris and Barbara Norfleet, alongside spreads from the newspapers and magazines that published their photographs, and contemporary works responding to the dissemination of the news today.

Pomegranates, or The Psychopharmacology of Everyday Myth

by Rafaël Newman

And the children of the moon / Were like a fork shoved on a spoon

Hedwig and the Angry Inch

1.

1.

The goddess Demeter, having received the Earth as her domain in the post-Titanic dispensation that followed the parricidal murder of her father Kronos, had mated with her brother Zeus, lord of the Sky, and borne a daughter, Persephone, whom she adored. Their brother Hades, meanwhile, whose dominion was the Underworld, was as yet without a wife; and his gaze now fell on his niece, Persephone. With his brother Zeus’s connivance he kidnapped the object of his desire, whereupon her mother Demeter subsided into melancholy and perpetual winter was visited upon the Earth: until an agreement was reached, to forestall the death of all creatures, and Persephone was allowed to return to the surface, on condition that she not have eaten anything while below. But Hades had in fact persuaded her to swallow six pomegranate seeds; and thus she was condemned to return to the Underworld henceforth for six months of the year, during which period her mother, Demeter, mourned for her, and the Earth was cast into darkness, and cold.

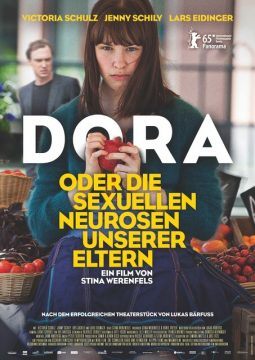

My daughter saw it immediately. We had just spent a week in Istanbul, and our daily dose of nar suyu, fresh-squeezed pomegranate juice, was still a pleasant sense memory; so she was primed to spot the plump fruit on the poster in the lobby of the cinema where we had gone to see Dora, oder die sexuellen Neurosen unserer Eltern (“Dora, or The Sexual Neuroses of Our Parents”). This was the pomegranate that had afforded her so much pleasure in Asia Minor, and which is reputed to have been the snake’s gift to Eve, and thus hers to Adam, in the Garden of Eden. This particular pomegranate, however, was part of a story of natural origins from a different cultural tradition, but was to prove no less my fruit of knowledge that evening as I began to decipher Stina Werenfels’ retelling of a myth central to western culture. A myth about fertility, and death, and love, and sex. And food. Read more »