by Thomas O’Dwyer

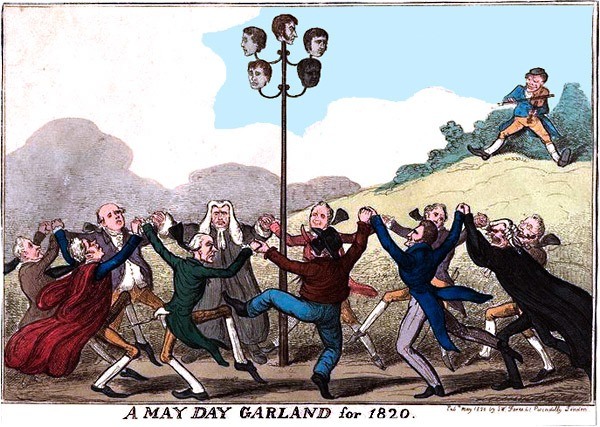

We still recall the 1920s as the Roaring Twenties or the Jazz Age. Not many will know that the decade which began 200 years ago with U.S. President James Monroe in office was the Era of Good Feelings, a name coined by a Boston newspaper. In 1820, a presidential election year, Monroe ran for his second term — he was unopposed, so there was really no campaign. He won all the electoral college votes except one, narrowly leaving George Washington to remain as the only president ever to score a unanimous victory.

In the flood of commentary, prophecy, gloom, and nostalgia that has greeted the start of a new decade, many of the comparisons with the past have fixed on the 1920s. That age is almost within living memory, maybe not personal, but at least familial, through the reminiscences and records of parents or grandparents. And for the first time in human history, we have extensive evidence in sound, film, and photography from the fascinating 1920s.

But is also interesting to look even further back, another 100 years, to the 1820s. For here, most people can agree, lie the true roots of the science-driven modernity that was more spectacularly obvious in the 1920s and beyond. Full documentary records in the 1820s were sparse but growing. Nicephore Niepce developed the first photograph in 1826 but sound reproduction would have to wait another 50 years for Thomas Edison. The first moving-picture sequence was made by Frenchman Louis le Prince in 1888. The new inventions and discoveries of the 1820s were physically primitive, but loaded with hidden significance and promise that no one could have guessed. Read more »

We find ourselves always in the middle of an experience. But it’s what we do next – how we characterize the experience – that lays down a host of important and almost subterranean conditions. Am I sitting in a chair, gazing out the dusty window into a world of sunlight, trees, and snow? Am I meditating on the nature of experience? Am I praying? Am I simply spacing out? Depending on which way I parse whatever the hell I’m up to, my experience shifts from something ineffable (or at any rate, not currently effed) to something meaningful and determinate, festooned with many other conversational hooks and openings: “enjoying nature”, “introspecting”, “conversing with God”, “resting”, “procrastinating”, and so on. Putting the experience into words tells me what to do with it next.

We find ourselves always in the middle of an experience. But it’s what we do next – how we characterize the experience – that lays down a host of important and almost subterranean conditions. Am I sitting in a chair, gazing out the dusty window into a world of sunlight, trees, and snow? Am I meditating on the nature of experience? Am I praying? Am I simply spacing out? Depending on which way I parse whatever the hell I’m up to, my experience shifts from something ineffable (or at any rate, not currently effed) to something meaningful and determinate, festooned with many other conversational hooks and openings: “enjoying nature”, “introspecting”, “conversing with God”, “resting”, “procrastinating”, and so on. Putting the experience into words tells me what to do with it next.

Forever is a long time.

Forever is a long time.

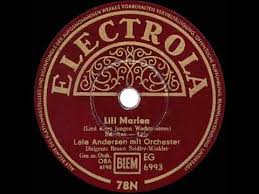

Lili Marleen is one of the best known songs of the twentieth century. A plaintive expression of a soldier’s desire to be with his girlfriend, it is indelibly associated with World War II, in part because it was popular with soldiers on both sides. It was

Lili Marleen is one of the best known songs of the twentieth century. A plaintive expression of a soldier’s desire to be with his girlfriend, it is indelibly associated with World War II, in part because it was popular with soldiers on both sides. It was  Marlene Dietrich, who worked tirelessly during world war two entertaining allied troops, also recorded both a

Marlene Dietrich, who worked tirelessly during world war two entertaining allied troops, also recorded both a

While waiting, shivering and jetlagged, for a train home from the Paris airport this week, I alternately stared into space and checked the train timetables. My train was an hour late. I later learned, thanks to the friendliness of a fellow traingoer, that the train had hit a deer.

While waiting, shivering and jetlagged, for a train home from the Paris airport this week, I alternately stared into space and checked the train timetables. My train was an hour late. I later learned, thanks to the friendliness of a fellow traingoer, that the train had hit a deer.

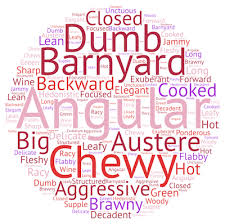

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists

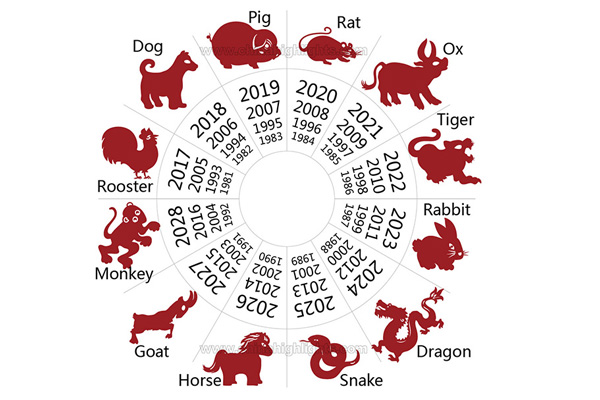

In the Chinese calendar, 2015 was the year of the sheep. I’m a sheep, and I briefly got into it. When you’re a sheep, you gotta own it.

In the Chinese calendar, 2015 was the year of the sheep. I’m a sheep, and I briefly got into it. When you’re a sheep, you gotta own it. Schoolteachers across the grades are responsible for teaching their students how to write. Their essential pedagogical role is instrumental. With particular attention paid to format, grammar, spelling, and syntax, students ideally learn to write what they know, think, or have learned. It matters little if the student is in a class for “creative writing” or “composition,” writing is taught and practiced as a way to record thoughts, compose ideas in a coherent manner, and clearly communicate information. A student’s writing is then assessed for how well she adhered to these instrumental standards while the teacher is assessed for how well she adhered to the standards of instrumental teaching.

Schoolteachers across the grades are responsible for teaching their students how to write. Their essential pedagogical role is instrumental. With particular attention paid to format, grammar, spelling, and syntax, students ideally learn to write what they know, think, or have learned. It matters little if the student is in a class for “creative writing” or “composition,” writing is taught and practiced as a way to record thoughts, compose ideas in a coherent manner, and clearly communicate information. A student’s writing is then assessed for how well she adhered to these instrumental standards while the teacher is assessed for how well she adhered to the standards of instrumental teaching.