by Ariane Koek

The architect Sou Fujimoto thinks of space as ‘densities’ and says architecture ‘is like handling the densities of the air’

“An endless sea of possibilities…of particles jumping in and out of existence” – that’s the description of space by the physicist Bilge Demirköz, who helped build the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS) detector on the International Space Station, thinks of space.

“Matter is creation, its evolution, it’s nature, it’s us” – that’s how Fashion designer Iris van Herpen describes matter. The physicist Michael Doser describes matter, the subject of his life’s work, as ‘massive, compace, heaty, light, transparent, filmy, an illusion.”

Different ways of looking at the same phenomena, revealing different ways of knowing and experiencing it through the mind or body or both. Laid out side by side in my book Entangle: Physics and the Artistic Imagination, seven physicists and seven artists individually explore what seven different phenomena mean to them. Their interviews reveal the differences as well as connections of seeing the same phenomena through different eyes. It is my belief that it is in the connections, the differences, and the gaps in between, that the two most unique aspects of being human thrive and grow – the sacred space of the imagination and creativity. Read more »

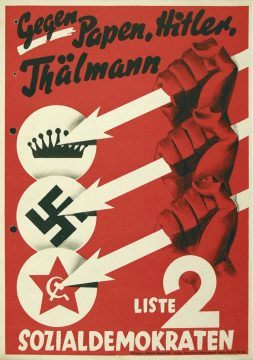

Most people associate the Cold War with several decades of intense political and economic competition between the United States and Soviet Union. A constant back and forth punctuated by dramatic moments such as the Berlin Airlift, the Berlin Wall, the arms race, the space race, the Bay of Pigs, the Cuban Missile Crisis, Nixon’s visit to China, the Olympic boycotts, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” and eventually the collapse of the Soviet system.

Most people associate the Cold War with several decades of intense political and economic competition between the United States and Soviet Union. A constant back and forth punctuated by dramatic moments such as the Berlin Airlift, the Berlin Wall, the arms race, the space race, the Bay of Pigs, the Cuban Missile Crisis, Nixon’s visit to China, the Olympic boycotts, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” and eventually the collapse of the Soviet system.

Where is philosophy in public life? Can we point to how the world in 2020 is different than it was in 2010 or 1990 because of philosophical research?

Where is philosophy in public life? Can we point to how the world in 2020 is different than it was in 2010 or 1990 because of philosophical research?

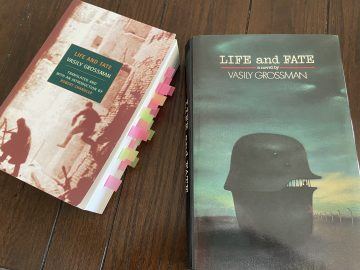

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in a typhoon of steel and firepower without precedent in history. In spite of telltale signs and repeated warnings, Joseph Stalin who had indulged in wishful thinking was caught completely off guard. He was so stunned that he became almost catatonic, shutting himself in his dacha, not even coming out to make a formal announcement. It was days later that he regained his composure and spoke to the nation from the heart, awakening a decrepit albeit enormous war machine that would change the fate of tens of millions forever. By this time, the German juggernaut had advanced almost to the doors of Moscow, and the Soviet Union threw everything that it had to stop Hitler from breaking down the door and bringing the whole rotten structure on the Russian people’s heads, as the Führer had boasted of doing.

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in a typhoon of steel and firepower without precedent in history. In spite of telltale signs and repeated warnings, Joseph Stalin who had indulged in wishful thinking was caught completely off guard. He was so stunned that he became almost catatonic, shutting himself in his dacha, not even coming out to make a formal announcement. It was days later that he regained his composure and spoke to the nation from the heart, awakening a decrepit albeit enormous war machine that would change the fate of tens of millions forever. By this time, the German juggernaut had advanced almost to the doors of Moscow, and the Soviet Union threw everything that it had to stop Hitler from breaking down the door and bringing the whole rotten structure on the Russian people’s heads, as the Führer had boasted of doing.

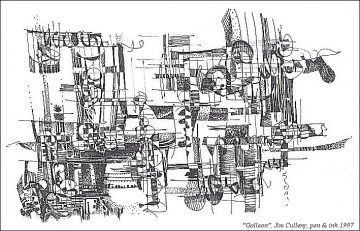

Ryan Ruby is a novelist, translator, critic, and poet who lives, as I do, in Berlin. Back in the summer of 2018, I attended an event at TOP, an art space in Neukölln, where along with journalist Ben Mauk and translator Anne Posten, his colleagues at the Berlin Writers’ Workshop, he was reading from work in progress. Ryan read from a project he called Context Collapse, which, if I remember correctly, he described as a “poem containing the history of poetry.” But to my ears, it sounded more like an academic paper than a poem, with jargon imported from disciplines such as media theory, economics, and literary criticism. It even contained statistics, citations from previous scholarship, and explanatory footnotes, written in blank verse, which were printed out, shuffled up, and distributed to the audience. Throughout the reading, Ryan would hold up a number on a sheet of paper corresponding to the footnote in the text, and a voice from the audience would read it aloud, creating a spatialized, polyvocal sonic environment as well as, to be perfectly honest, a feeling of information overload. Later, I asked him to send me the excerpt, so I could delve deeper into what he had written at a slower pace than readings typically afford—and I’ve been looking forward to seeing the finished project ever since. And now that it is, I am publishing the first suite of excerpts from Context Collapse at Statorec, where I am editor-in-chief.

Ryan Ruby is a novelist, translator, critic, and poet who lives, as I do, in Berlin. Back in the summer of 2018, I attended an event at TOP, an art space in Neukölln, where along with journalist Ben Mauk and translator Anne Posten, his colleagues at the Berlin Writers’ Workshop, he was reading from work in progress. Ryan read from a project he called Context Collapse, which, if I remember correctly, he described as a “poem containing the history of poetry.” But to my ears, it sounded more like an academic paper than a poem, with jargon imported from disciplines such as media theory, economics, and literary criticism. It even contained statistics, citations from previous scholarship, and explanatory footnotes, written in blank verse, which were printed out, shuffled up, and distributed to the audience. Throughout the reading, Ryan would hold up a number on a sheet of paper corresponding to the footnote in the text, and a voice from the audience would read it aloud, creating a spatialized, polyvocal sonic environment as well as, to be perfectly honest, a feeling of information overload. Later, I asked him to send me the excerpt, so I could delve deeper into what he had written at a slower pace than readings typically afford—and I’ve been looking forward to seeing the finished project ever since. And now that it is, I am publishing the first suite of excerpts from Context Collapse at Statorec, where I am editor-in-chief.

The case for men’s rights follows straightforwardly from the feminist critique of the structural injustice of gender rules and roles. Yes, these rules are wrong because they oppress women. But they are also wrong because they oppress men, whether by causing physical, emotional and moral suffering or callously neglecting them. Unfortunately the feminist movement has tended to neglect this, assuming that if women are the losers from a patriarchal social order, then men must be the winners.

The case for men’s rights follows straightforwardly from the feminist critique of the structural injustice of gender rules and roles. Yes, these rules are wrong because they oppress women. But they are also wrong because they oppress men, whether by causing physical, emotional and moral suffering or callously neglecting them. Unfortunately the feminist movement has tended to neglect this, assuming that if women are the losers from a patriarchal social order, then men must be the winners.