by Tim Sommers

So, here’s a game. Try to imagine: “What unbelievable moral achievements might humanity witness a century from now?” Now, discuss.

So, here’s a game. Try to imagine: “What unbelievable moral achievements might humanity witness a century from now?” Now, discuss.

“The trick, of course, is that if you can seriously contemplate its occurring, you are thinking too small, or so history suggest.” So says David Estlund who proposes “The Unbelievable Moral Progress Game” in his new book “Utopophobia: On the Limits (If Any) of Political Philosophy”.

The argument that political philosophy is, or theories of justice are, too often unrealistic is familiar enough. Estlund turns that argument on its head. He argues (among other things) that, at least sometimes, political philosophy is not unrealistic enough. Or, at least, that we should not be afraid to imagine the highly-unlikely, even the impossible, when thinking about what might be possible for us morally and politically.

Estlund’s previous book, “Democratic Authority”, besides being an influential, admirably clear, and widely read work on democracy is the source of the word. “Epistocracy.” It means the rule of the knowledgeable. You may have heard of it. He’s against it.

In “Utopophobia”, he takes head-on on a wide-variety of entertaining, often challenging, topics around the theme, obviously, of the wide-spread allergic reaction to utopianism in our culture. (In an earlier column, I used his “fallacy of approximation”. (“What if Equality of Opportunity is a Bad Idea?”) To simplify a bit, “It is not the case that where the first best solution is not available, the second best is always to be preferred.”) But this is not a book review. Let’s play the game.

There are real cases of unbelievable moral progress. Estlund mentions (among other things) the abolition of slavery and the legalization of same sex marriage. I asked a number of people for their thoughts on what the next great leap forward might me. (The list of those people is at the bottom.) This is some of what some of them said. Read more »

The translated versions from Tamil into English of Perumal Murugan’s two books, One Part Woman and the The Story of A Goat, weave stories of the complex life of the rural people of South India in an engaging and highly readable form.

The translated versions from Tamil into English of Perumal Murugan’s two books, One Part Woman and the The Story of A Goat, weave stories of the complex life of the rural people of South India in an engaging and highly readable form. Jack Youngerman. Long March II, 1965.

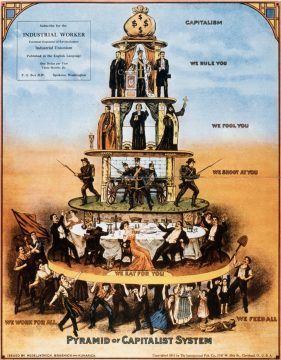

Jack Youngerman. Long March II, 1965. The political philosophy, and more importantly, political practice that took root in the wake of the ‘Age of Revolutions’ (say 1775-1848) was liberalism of various kinds: a commitment to certain principles and practices that eventually came to seem, like any successful ideology, a kind of common sense. With this, however, came a growing sense of dissatisfaction with what it seemed to represent: ‘bourgeois society’. Here is a paradox: at the very point at which the Enlightenment promise of the free society seemed to be coming true, discontent with that promise, or with the way it was being fulfilled, took hold. This was a sense that the modern citizen and subject was somehow still unfree. If this seems at least an aspect of how things stand with us in 2020 it might be worth looking back, for doubts about the liberal project have accompanied it since its inception.

The political philosophy, and more importantly, political practice that took root in the wake of the ‘Age of Revolutions’ (say 1775-1848) was liberalism of various kinds: a commitment to certain principles and practices that eventually came to seem, like any successful ideology, a kind of common sense. With this, however, came a growing sense of dissatisfaction with what it seemed to represent: ‘bourgeois society’. Here is a paradox: at the very point at which the Enlightenment promise of the free society seemed to be coming true, discontent with that promise, or with the way it was being fulfilled, took hold. This was a sense that the modern citizen and subject was somehow still unfree. If this seems at least an aspect of how things stand with us in 2020 it might be worth looking back, for doubts about the liberal project have accompanied it since its inception.

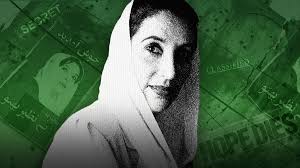

As she returned to her country after eight years of self-imposed exile in Dubai, Benazir reflected in her posthumously-published memoir

As she returned to her country after eight years of self-imposed exile in Dubai, Benazir reflected in her posthumously-published memoir  Gibraltar in the background, I pose sideways, wearing a Spanish Chrysanthemum claw in my hair, gitana style, taking a dare from my husband. The photo is from an August afternoon, captured in the sun’s manic glare. My shadow in profile, with the oversized flower behind my ear, mirrors the shape of Gibraltar, Jabl ut Tariq or “Tariq’s rock.” An actual visit to Gibraltar is more than a decade ahead in the future. I would spend years researching the civilization of al Andalus (Muslim Spain, 711-1492) and publish a book about the convivencia of the Abrahamic people before finally setting foot on Gibraltar. “In Cordoba,” I write, “I’m inside the tremor of exile— the primeval, paramount home of poetry” and that “I am drawn to the world of al Andalus because it is a gift of exiles, a celebration of the cusp and of plural identities, the meeting point of three continents and three faiths, where the drama of boundaries and their blurring took place.” At the heart of this pursuit is my own story, one that is illuminated only recently when I see in Gibraltar more facets of my own exile and encounter with borders.

Gibraltar in the background, I pose sideways, wearing a Spanish Chrysanthemum claw in my hair, gitana style, taking a dare from my husband. The photo is from an August afternoon, captured in the sun’s manic glare. My shadow in profile, with the oversized flower behind my ear, mirrors the shape of Gibraltar, Jabl ut Tariq or “Tariq’s rock.” An actual visit to Gibraltar is more than a decade ahead in the future. I would spend years researching the civilization of al Andalus (Muslim Spain, 711-1492) and publish a book about the convivencia of the Abrahamic people before finally setting foot on Gibraltar. “In Cordoba,” I write, “I’m inside the tremor of exile— the primeval, paramount home of poetry” and that “I am drawn to the world of al Andalus because it is a gift of exiles, a celebration of the cusp and of plural identities, the meeting point of three continents and three faiths, where the drama of boundaries and their blurring took place.” At the heart of this pursuit is my own story, one that is illuminated only recently when I see in Gibraltar more facets of my own exile and encounter with borders.

Most people associate the Cold War with several decades of intense political and economic competition between the United States and Soviet Union. A constant back and forth punctuated by dramatic moments such as the Berlin Airlift, the Berlin Wall, the arms race, the space race, the Bay of Pigs, the Cuban Missile Crisis, Nixon’s visit to China, the Olympic boycotts, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” and eventually the collapse of the Soviet system.

Most people associate the Cold War with several decades of intense political and economic competition between the United States and Soviet Union. A constant back and forth punctuated by dramatic moments such as the Berlin Airlift, the Berlin Wall, the arms race, the space race, the Bay of Pigs, the Cuban Missile Crisis, Nixon’s visit to China, the Olympic boycotts, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” and eventually the collapse of the Soviet system.

Where is philosophy in public life? Can we point to how the world in 2020 is different than it was in 2010 or 1990 because of philosophical research?

Where is philosophy in public life? Can we point to how the world in 2020 is different than it was in 2010 or 1990 because of philosophical research?

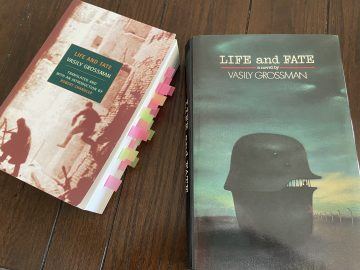

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in a typhoon of steel and firepower without precedent in history. In spite of telltale signs and repeated warnings, Joseph Stalin who had indulged in wishful thinking was caught completely off guard. He was so stunned that he became almost catatonic, shutting himself in his dacha, not even coming out to make a formal announcement. It was days later that he regained his composure and spoke to the nation from the heart, awakening a decrepit albeit enormous war machine that would change the fate of tens of millions forever. By this time, the German juggernaut had advanced almost to the doors of Moscow, and the Soviet Union threw everything that it had to stop Hitler from breaking down the door and bringing the whole rotten structure on the Russian people’s heads, as the Führer had boasted of doing.

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in a typhoon of steel and firepower without precedent in history. In spite of telltale signs and repeated warnings, Joseph Stalin who had indulged in wishful thinking was caught completely off guard. He was so stunned that he became almost catatonic, shutting himself in his dacha, not even coming out to make a formal announcement. It was days later that he regained his composure and spoke to the nation from the heart, awakening a decrepit albeit enormous war machine that would change the fate of tens of millions forever. By this time, the German juggernaut had advanced almost to the doors of Moscow, and the Soviet Union threw everything that it had to stop Hitler from breaking down the door and bringing the whole rotten structure on the Russian people’s heads, as the Führer had boasted of doing.