by Jonathan Kujawa

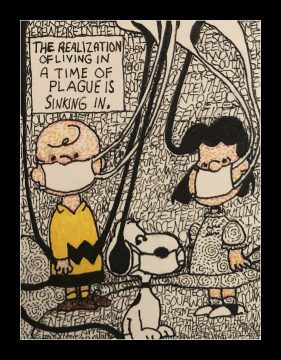

For mathematics, 1666 was the Annus Mirabilis (“wonderous year”). For the rest of humanity, it was pretty terrible. The plague once again burnt across Europe [1]. Cambridge University closed its doors and Issac Newton moved home.

Although only twenty-three years old, Newton was pretty well caught up to the state of the art in math and physics. Newton was brilliant, of course, but it also wasn’t so hard for an educated person to be at the cutting edge. After all, it was only thirty years earlier that Descartes and Fermat had introduced the notion of using letters (like x and y) for unknowns and had the insight that by plotting points on the xy-plane you could view algebra and geometry as two sides of the same coin.

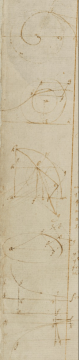

With nothing better to do while quarantined at the family home, Newton settled back into the study of math and physics and, it turns out, ignited several world-changing revolutions in the process. Newton cracked open a 1000 page notebook he had inherited from his stepfather and got to work, recording his thoughts as he went. After reading Euclid’s Elements (still the gold standard after nearly 2,000 years!), Descartes, and the other books he had on hand, Newton began posing ever harder questions for himself which he then solved, inventing new math along the way.

Amazingly, Newton’s notebook (which he called his “Waste Book”) still exists! It is kept by the Cambridge University library along with thousands of pages of his other writings. In fact, you can read it for yourself online at the University’s website.

Some of the questions Newton posed could be considered standard, even for his day: computing roots, solving problems in geometry, and the like. Others are more open-ended: “If a Staffe bee bended to find the crooked line which it resembles.” or “To find such lines whose areas length or centers of gravity may bee found.”

In due course, Newton asks himself questions we recognize as the forerunners of calculus. Read more »

Kazuo Shiraga. Untitled 1964.

Kazuo Shiraga. Untitled 1964. There has been much discussion lately of whether the COVID-19 pandemic will spell the end of globalization. It’s hard to get economists to agree on the meaning of the numbers, or foreign policy analysts to commit to a vision of the future in a world that changes from one moment to the next. Globalization means different things to different people and entities. Its many facets, and many narratives about those facets, complicate discussion about either a contraction or a resurgence of globalization. For corporations, it means access to inexpensive labor markets; for money managers, it means access to capital markets. For the typical business traveler, it may mean something as basic as greater choice of airlines and flight times for an international trip. For an optimistic humanist, it might symbolize enhanced international cooperation and a suppression of nationalism and xenophobia. For an environmentalist, it is marred by the dangerous policies that accelerate climate change. For a technocrat, it seems the obvious economic approach to accompany the paradigm of social-media-fueled connectedness, data collection, surveillance, and targeted marketing.

There has been much discussion lately of whether the COVID-19 pandemic will spell the end of globalization. It’s hard to get economists to agree on the meaning of the numbers, or foreign policy analysts to commit to a vision of the future in a world that changes from one moment to the next. Globalization means different things to different people and entities. Its many facets, and many narratives about those facets, complicate discussion about either a contraction or a resurgence of globalization. For corporations, it means access to inexpensive labor markets; for money managers, it means access to capital markets. For the typical business traveler, it may mean something as basic as greater choice of airlines and flight times for an international trip. For an optimistic humanist, it might symbolize enhanced international cooperation and a suppression of nationalism and xenophobia. For an environmentalist, it is marred by the dangerous policies that accelerate climate change. For a technocrat, it seems the obvious economic approach to accompany the paradigm of social-media-fueled connectedness, data collection, surveillance, and targeted marketing.

1. As the coronavirus continues to disrupt human life in many corners of the globe, a phrase from George Frideric Handel’s Messiah has wormed its way through the background noise of my attention span. It occurs in a Part III

1. As the coronavirus continues to disrupt human life in many corners of the globe, a phrase from George Frideric Handel’s Messiah has wormed its way through the background noise of my attention span. It occurs in a Part III  We get half a sunny day every other day since Corona has coaxed us to quit public spaces. In the past fortnight or so, sunlight has been in short supply just as masks, disinfectant spray and toilet paper. When the sun is out, it’s no ordinary gift; it brings a rush of joy that wipes out not only the free-floating, dystopic COVID -19 anxiety, but also the other recent traumas we’ve faced as a family. Indoors, socially-distant by three feet, hunched over our phones for news of loved ones, we forget it is spring, but mornings the sunlight hits the windows feel as if God has turned on the power-wash setting: one is shocked into vigor, tricked into optimism. On such a day, I step down the patio threshold as if pulled by a magnet; just out of the shower and still combing my wet hair, I’m suddenly aware of another gift— soap.

We get half a sunny day every other day since Corona has coaxed us to quit public spaces. In the past fortnight or so, sunlight has been in short supply just as masks, disinfectant spray and toilet paper. When the sun is out, it’s no ordinary gift; it brings a rush of joy that wipes out not only the free-floating, dystopic COVID -19 anxiety, but also the other recent traumas we’ve faced as a family. Indoors, socially-distant by three feet, hunched over our phones for news of loved ones, we forget it is spring, but mornings the sunlight hits the windows feel as if God has turned on the power-wash setting: one is shocked into vigor, tricked into optimism. On such a day, I step down the patio threshold as if pulled by a magnet; just out of the shower and still combing my wet hair, I’m suddenly aware of another gift— soap.

I was a minor mess in high school. Had no idea what to do with my curly hair. Unduly influenced by a childhood spent watching late ‘70s television, I stubbornly brushed it to the side in a vain attempt to straighten and shape it into a helmet à la The Six Million Dollar Man or countless B-actors on The Love Boat and Fantasy Island. I couldn’t muster any fashion beyond jeans, t-shirts, and Pumas. In the winter I wore a green army coat. In the summer it was shorts and knee high tube socks.

I was a minor mess in high school. Had no idea what to do with my curly hair. Unduly influenced by a childhood spent watching late ‘70s television, I stubbornly brushed it to the side in a vain attempt to straighten and shape it into a helmet à la The Six Million Dollar Man or countless B-actors on The Love Boat and Fantasy Island. I couldn’t muster any fashion beyond jeans, t-shirts, and Pumas. In the winter I wore a green army coat. In the summer it was shorts and knee high tube socks.

I must admit that when I first flipped through Capitalism on Edge: How Fighting Precarity Can Achieve Radical Change Without Crisis or Utopia by Albena Azmanova, it did not look too inviting. The blurbs on the jacket did nothing to reassure me, suggesting that this was yet another post-Marxist critique of greedy capitalists and their enablers. As it turns out, it is, but in a way that is more interesting than I had assumed. As soon as I started reading the Introduction, I was gripped by the lucidity of ideas and clarity of the prose. For an academic text written from the perspective of Critical Theory, this is a wonderfully direct, incisive and insightful book. One does not need to agree with all the details of the analysis to find reading it a rewarding experience.

I must admit that when I first flipped through Capitalism on Edge: How Fighting Precarity Can Achieve Radical Change Without Crisis or Utopia by Albena Azmanova, it did not look too inviting. The blurbs on the jacket did nothing to reassure me, suggesting that this was yet another post-Marxist critique of greedy capitalists and their enablers. As it turns out, it is, but in a way that is more interesting than I had assumed. As soon as I started reading the Introduction, I was gripped by the lucidity of ideas and clarity of the prose. For an academic text written from the perspective of Critical Theory, this is a wonderfully direct, incisive and insightful book. One does not need to agree with all the details of the analysis to find reading it a rewarding experience.

Sughra Raza. Mid-winter Fall. February 2020.

Sughra Raza. Mid-winter Fall. February 2020.