by Joan Harvey

It’s a foggy gray day and the stock market is in free fall. Last week, because I’m one of those careless people who doesn’t pay too much attention to these things, I decided to go against my grain and try to educate myself a little more about the new plague. It is, anyhow, almost impossible not to think about. A short time ago it all seemed very abstract; there were only a few cases in America, and only two in Colorado. Today, although now there are only eight cases in Colorado (whoops, now nine, wait, now 17, today 33, now 77), everything looks grim. With the spread of the virus my thinking and behavior have had to keep evolving daily. And writing about this changing scenario begins to feel like trying to catch a greased pig. One day we’re behaving normally, scoffing at people in a shopping frenzy; the next week the WHO declares a pandemic and we realize we’ve seen nothing like this in our lifetime.

In an old issue of Cabinet Magazine from Fall/Winter 2003 (for some unknown reason stored on my computer), I come across an article by David Serlin, with the clever title, SARS Poetica. While SARS was far less dangerous, I’m still struck by how much in common that virus from almost 20 years ago has with our current bug: infection originating in China from the human consumption of exotic animals–in that case civet cats, in this case probably bats but possibly pangolins or possibly something else; the Chinese government in both cases concealing information about the epidemic; the photos of empty public spaces; the lost business revenue. Serlin points out that the economic losses by business were identified as the tragic victims of the virus, far more than were the actual human victims.

SARS had a catchy name—the acronym went down so well that I didn’t even remember that it stood for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. So far this coronavirus, though also a SARS virus, does not fit into one slick syllable; coronavirus is the name that has stuck. Sara Harrison, writing in Wired, tells us a little more about the naming:

The international committee tasked with officially classifying viruses has named the new one SARS-CoV-2, because of its close genetic ties to another coronavirus, the one that causes SARS. However, the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2—remember, that’s the disease characterized by coughing, fever, and respiratory distress—is called Covid-19. It’s the name officially bestowed upon the ailment by the World Health Organization. WHO’s task was to find a name that didn’t demonize a particular place, animal, individual, or group of people, and which was also pronounceable. It’s pronounced just like it sounds: Co-Vid-Nine-teen.

As a person not nearly as concerned about the virus as I learned I should be (most of my friends were not particularly worried either), I wanted to make some sense of the threat that became increasingly impossible to ignore. First a significant part of China was shut down, and then Italy, and now New Rochelle. As I write, the governor of Colorado has just declared a State of Emergency and the University of Colorado is closed. Headline after headline in every newspaper is about the virus. For a while, as with SARS, most of the headlines were about economics: threats to the travel industry, to the entertainment industry, to people’s livelihoods, the cost of healthcare, and of course the violent plunge of the stock market. But because this virus is much more widespread, the emphasis has shifted to number of cases, number of deaths, lack of tests – as of March 8, America had tested 5 people per million, compared to Italy’s 826 people per million. Another difference this time around are all the articles about the continued spread of false information by the White House. As usual, Andy Borowitz gets it right.

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said on Thursday that the man had ignored the advice of public-health experts and spewed a toxic strain of ignorance, potentially infecting millions.

Even what seem like respectable news sources give confusing reports. Two articles come up side by side on my feed, with opposite headlines. CNBC reported that the global death rate was higher than previously thought, but immediately next to it an article from Slate said that the COVID virus wasn’t as deadly as we think. Most sources say that the virus can spread with no symptoms, but a doctor reporting from China says that there are very few asymptomatic cases.

I don’t remember ever paying any attention to SARS or trying to do anything to avoid it, or being afraid of it at all, though I was the parent of a young child at the time. It turns out I wasn’t the only one. Wang Xiuying, currently under quarantine in Wuhan, writes that he was in graduate school in Shanghai at the time of SARS, and it barely caused a ripple there. This coronavirus is far more dangerous, and the scale of the fears is also multiplied by the difference between the internet then and the internet now. Then was pre-Facebook, pre-Twitter, pre-most-fake-news. As Charlie Wurzel writes in the New York Times, “Literal virality and online virality begin to mimic and influence each other.” On the other hand, we’re lucky to also have the spread of real reports so we take this pandemic seriously.

We’re already drowning in existential threat from climate catastrophe, looming fascism, a president who can’t make a complete sentence and who has decimated the CDC. Even so, for a while, it felt somewhat ridiculous to stock up and hunker down. Nothing much had changed among the people we knew; would having lots of pantry staples and hand sanitizer really do anyone any good? Today in town people are still out, sitting at group tables in cafés, enjoying time together. But we see what happened in Italy, we recognize the idiocy of our leader, and some of us, who can, stay home. After more news, we understand. The only way to help contain this is through social distancing. Even the most blasé among us have to get onboard.

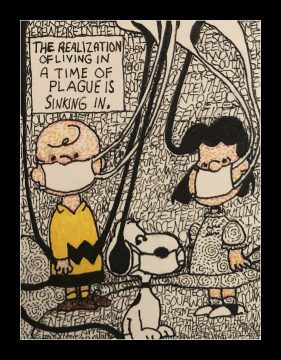

I was raised playing in dirt, by parents who dismissed illness, including a dislocated knee cap, with the all-purpose phrase, “You’ll be better in the morning.” There were many of us kids, and no room for fussiness or complaint. Stoicism was the only supported style. I’m still not particularly worried about the virus, but my insouciance is actually possibly the threat, as my immune system is, apparently, quite weird and various cells aren’t doing what they should. I don’t have any terrible disease, I’m very healthy (knock on wood), but according to the immunologist whom I saw before all this virus news, I am quite possibly vulnerable to infection. And of course any carelessness on my part is dangerous to others. Still, the thought of wearing a mask, for example, horrifies me on many levels: a wee bit of claustrophobia, the weird showiness of it, the outward demonstration of fear. Of course, most masks don’t really do any good, and of course I’m not someone who bothered to buy one when they were available. And, fortunately, in case of need, my partner has dug up an old painter’s mask that might do the trick if absolutely necessary.

A Korean woman who self-identifies as a germophobe has the exact opposite reaction to masks that I do–she’s discomfited by the idea of not wearing one. But she wrote that on her next flight she wouldn’t wear a mask because it would contribute to stereotyping against her. It’s not only the virus that is spreading; as with many of our overwrought fears, so is racism. After sensing people looking at him at the airport, Asian-American writer Karl Chwe reports:

Asian-Americans enjoy a unique privilege among minorities: White people don’t usually fear or despise us, and my obliviousness is evidence of that privilege. But that might be changing. It occurred to me on the plane that this must be like what some Black or Latinx or Muslim people sometimes feel—the uncertain itch, where you can’t tell quite what’s going on.

Week before last we went to a Chinese restaurant in Denver, one of those new hip places with no Chinese people in sight. It was completely packed, mostly with young people; not everyone was staying home. But this was before any cases were reported in Denver, before our governor had declared a State of Emergency, and most of the people out were young and healthy. Even today, after our State of Emergency has been declared, my Congressman invites me to a luncheon for Women’s History Month. I won’t go, but even among the well-informed there is still confusion about how to behave. (The lunch has since been postponed.)

I figured that in addition to all the social and economic destruction, I should try to find out more about what the virus actually does to the body, and then immediately regretted doing so. Most cases are mild, but the other 18-25 percent go through a severe or critical phase that sounds nasty and gnarly. Some people survive, but with permanent lung damage and holes in their lungs. Infection can hit the intestines, followed by liver and kidney damage. In fighting the virus the body can unleash a cytokine storm, proteins that go overboard in fighting the infection, but in doing so attack healthy tissue as well as infected cells. Was I really thinking it would be a pretty picture?

It has been estimated that between 40 and 70 percent of the world’s adults will get the coronavirus. Marc Lipsitch, Harvard epidemiologist and the director of the Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics, has called the U.S. response “utterly inadequate.” A woman in Washington State tweets that she has a history of respiratory problems, works with an elderly population, and thinks she might possibly be infected, but, no matter whom she calls, she is unable to get tested. Another woman writes in the New York Times of her many attempts to get a test, her visits to the ER with no luck, her success in getting tested only when she told them she was writing about the issue. Even if tests become available, Dr. Bruce Aylward points out, many Americans may be afraid to get tested because of medical bills. And this doesn’t address the undocumented immigrants who will fear being entered into any public system. We are, as a country, woefully unprepared. Martin Mackary reports that the U.S. has approximately 100,000 ICU beds with most hospitals already functioning at full or near-full capacity. But 200,000 to 2.9 million patients could turn up in hospitals with the coronavirus, and this doesn’t account for all the others who need emergency care.

For those who potentially have the virus, but aren’t seriously ill, true self-quarantining also sounds like a bear: one has to isolate oneself away from partners and children and possibly even pets. Worse are the economic effects. Not everyone can work from home. Not everyone can survive without a paycheck. And one doesn’t have to be ill, or live close to anyone ill, to lose customers in one’s small business and be forced to lay off employees, who in turn lose their paycheck and their ability to buy food. This tiny submicroscopic thing has completely disrupted the whole world. Samuel Veissière writes in Psychology Today:

By exploiting vulnerabilities in human psychology selectively bred by its pathogen ancestors, it has already shut down many of our schools, crashed our stock market, increased social conflict and xenophobia, reshuffled our migration patterns, and is working to contain us in homogenous spaces where it can keep spreading.

Nicolas Kristof reminds us that Swine Flu hit red states hardest. Because Swine Flu happened under Obama, vaccines and health care were dismissed by people like Rush Limbaugh (and also Trump at the time) as a hoax. People in red states were less likely to be vaccinated and more likely to die. It is perhaps easier to think about this virus than about current politics, but obviously the handling of the virus is political. As I write, Democrats in Congress are hoping to rush through a bill that will help Americans during the outbreak. The bill is expected to include paid sick leave and could also expand federal food aid programs. Will the Republicans vote against this? Who knows? They’ve just prevented an emergency paid sick leave bill from going to the floor, but the virus is causing everyone to change their regular behavior. If after the last SARS outbreak, money had funded more studies rather than letting them lapse, we might be in better shape, but we tend to support science only if there is profit in it. If research teams were more able to cooperate in studying the virus and finding vaccines, rather than needing to compete for funds and status, we might be far ahead of the game.

Trump is using the virus as a way to promote stricter border security, as well as more tax cuts, and to continue his trade war with China. The facts, as usual, make no difference. An immigration judge reports that the Executive Office for Immigration Review has ordered immigration court staff to remove CDC posters designed to slow the spread of the coronavirus. I confess it is hard to believe that Trump’s executive branch isn’t eager for the virus to infect recent immigrants so that they can blame them and get rid of them more easily. The current administration must be unhappy that this virus has been transmitted not by desperately poor people coming in from the southern border, but by people wealthy enough for international travel and cruises.

After SARS, people killed lots of civet cats, blaming them for the virus. Will they go after pangolins this time round? Our basic irrationality is foregrounded. A person sneezes on a plane to Newark; the pilot has to land prematurely when other passengers become unruly. I find myself wanting to buy a forlorn case of Corona beer, just because of the stupidity surrounding the whole thing. Shelves are cleaned out of NSAIDS and cold remedies. What will people do who must take aspirin every day if there is none in the stores? So far the CDC has said that unless one is going to China, Iran, Italy, or South Korea there is no reason to stay off airplanes. But wait. Under Trump we can’t trust the CDC.

People share pleas from immunologists to stay in, pleas from others to live as normally as possible without fear. Bill Maher insists we should give up all sugar to stay healthy. Jim Bakker pushes some cure-all silver solution for $149. A friend advises us to drink his delicious kombucha. I’m having to learn that stoicism is not always a smart habit. And to pay attention to the consensus that social distancing is the only possible way to avoid complete disaster. This doesn’t have to mean always being alone. In her excellent article on flattening the curve, Julie McMurry points out that you can be creative about this; for example, you can walk with friends outside, or have a picnic in the warm spring sun. Others suggest a mixing yourself a nice quarantini; just like a martini, but you drink it alone in your house. You can check out Rabih Alameddine’s Noli Me Tangere Twitter thread. Or sing “I Will Survive” along with Gloria Gaynor as you conscientiously wash your hands.

Michael Meade tells us this is the year of the Metal Rat. In the West rats are connected to the history of the plague and other viruses, but in China, he says, they are known for their resiliency, their flexibility, their way of surviving. Li Edelkoort, a “design industry advisor,” is described in Quartz as believing that because the virus will make people live more quietly and keep them from jet-setting, it may provide the answer to our overheated forms of consumption and our overly stressful lives. Both Meade and Edelkoort offer comforting thoughts, but quite possibly false positives.

Still, in all this, there are moments of beauty. Pornhub, out of the sheer goodness of its heart, is giving Italians free premium access during their painful quarantine.