by Eric J. Weiner

Dedication

Dedication

As an “intellectual in emigration,” Theodor Adorno wrote Mimima Moralia, his book of philosophical, sociological, cultural, and psychological reflections “from the standpoint of subjective experience, [which] means that the pieces do not entirely measure up to the philosophy, of which they are nevertheless a part.” I have always been fascinated by this book. As form follows function, he uses common aphorisms as a springboard for this particular advance of critical theory; each section is a short but deep dive into the very essence of the experience about which he ruminates. As an intellectual in quarantine away from my home, I felt some loose kinship to Adorno’s condition of displacement and found the form compelling as well as comforting. My mind and spirit are restless and conflicted; protected yet partially blinded by my shelter, I nevertheless try to see, understand and find a kind of educated hope in the fact that through critical reflection there are pedagogical moments in the present and past from which to learn and grow.

Part One

2020

Nothing is harmless anymore–Theodor Adorno

1

Fly like a butterfly, sting like a bee–Often referenced as the shortest poem ever written, Muhammad Ali’s poem “Me, We!” captures in the most succinct way the challenges that the coronavirus pandemic presents to a species not quite ready for primetime. According to George Plimpton in the film When We Were Kings, after Ali completed his commencement address to Harvard’s graduating class of ‘75, a student yelled out from the audience, “Give us a poem!” I imagine “The Greatest” looking out from the podium over the congregation of overwhelmingly white faces—punctuated like an exclamation point by the occasional brown one—and spreading his famously long arms as if getting ready to accept the love of a neglected child. A grin widens across that beautifully regal face as he recites, “Me, We!”; a stinging jab, followed by a powerful overhand right.

2

You never forget how to ride a bike—Reuters, April 4, 2020, journalist Gabriella Borter writes, “Hospitals and morgues in [New York City] are struggling to treat the desperately ill and bury the dead. Crematories have extended their hours and burned bodies into the night, with corpses piling up so quickly that city officials were looking elsewhere in the state for temporary interment sites.” My nine-year-old daughter, on this same day, in a town about eighty-five miles from the crematories and refrigerated temporary morgues, learns to ride her bike. A northwest wind rips open several days of raw rain, ushering in chilly spring air, cerulean sky, and bursts of Goldenrod along the harbor’s edge. It takes just a short jog and gentle push from me to send her off into that magical moment in which velocity, gravity and centrifugal force mix with our human capacity, need and desire for balance; her triumphant laughter and hoots of delight are stolen by the wind as she pedals her bike farther and farther away from me. Read more »

Violence : War :: Lies : Mythology

Violence : War :: Lies : Mythology

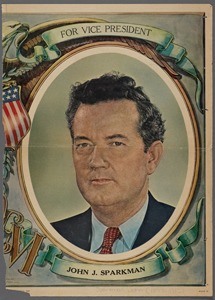

That Fifties-looking gent to your right is John J. Sparkman (D-Alabama) who was Adlai Stevenson’s running mate in 1952. Sparkman served in Congress for more than 40 years, the last 32 of them in the Senate. While not a star, he was associated with several pieces of important legislation and became Chair of the Senate Banking Committee and, late in his career, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He was also a committed segregationist and, in 1956, signed the Southern Manifesto, in emphatic opposition to Brown vs. Board of Education.

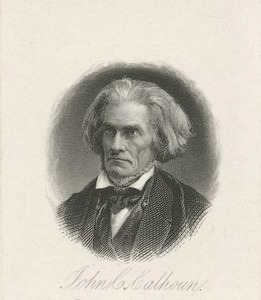

That Fifties-looking gent to your right is John J. Sparkman (D-Alabama) who was Adlai Stevenson’s running mate in 1952. Sparkman served in Congress for more than 40 years, the last 32 of them in the Senate. While not a star, he was associated with several pieces of important legislation and became Chair of the Senate Banking Committee and, late in his career, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He was also a committed segregationist and, in 1956, signed the Southern Manifesto, in emphatic opposition to Brown vs. Board of Education. This scary-looking guy to your left is John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, who, during a truly extraordinary career that included being a Congressman, Senator, Secretary of State, and Secretary of War, also managed to sneak in two terms as Vice President under two very different Presidents, John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. You are going to hear a lot over the next few weeks about “chemistry” between Joe Biden and his running mate. Suffice it to say that John C. Calhoun never had chemistry with anyone, except perhaps of the combustible kind. Mr. Jackson and Mr. Calhoun disagreed constantly, particularly on the enforcement of federal laws that South Carolina found not to its liking (including the juicily named “Tariff of Abominations”), which led Mr. Calhoun to resign the Vice Presidency during the Nullification Crisis in 1832.

This scary-looking guy to your left is John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, who, during a truly extraordinary career that included being a Congressman, Senator, Secretary of State, and Secretary of War, also managed to sneak in two terms as Vice President under two very different Presidents, John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. You are going to hear a lot over the next few weeks about “chemistry” between Joe Biden and his running mate. Suffice it to say that John C. Calhoun never had chemistry with anyone, except perhaps of the combustible kind. Mr. Jackson and Mr. Calhoun disagreed constantly, particularly on the enforcement of federal laws that South Carolina found not to its liking (including the juicily named “Tariff of Abominations”), which led Mr. Calhoun to resign the Vice Presidency during the Nullification Crisis in 1832. They hauled us all in bas minis from the ranger station to the trailhead. From there, a six-kilometer trail led up to our destination, the Laban Ratah guest house, at 11,000 feet. At 13,432 feet, Mt. Kinabalu’s summit, in Malaysian Borneo, is the highest point in Southeast Asia.

They hauled us all in bas minis from the ranger station to the trailhead. From there, a six-kilometer trail led up to our destination, the Laban Ratah guest house, at 11,000 feet. At 13,432 feet, Mt. Kinabalu’s summit, in Malaysian Borneo, is the highest point in Southeast Asia.

The word “interpretivism” suggests to most people a particularly crazy sort of postmodern relativism cum skepticism. If our relations to reality are merely interpretive and perspectival (I will use these terms interchangeably as needed, the idea being that each

The word “interpretivism” suggests to most people a particularly crazy sort of postmodern relativism cum skepticism. If our relations to reality are merely interpretive and perspectival (I will use these terms interchangeably as needed, the idea being that each

Stefany Anne Golberg’s

Stefany Anne Golberg’s

As we continue to distance ourselves from others in the midst of the new coronavirus pandemic, we hear about other people’s new rituals and routines as we formulate our own. As each day to be spent at home stretches (looms) ahead of us when we awake in the morning, rituals give the day shape, symmetry, a framework. What significance do these new rituals have for us individually and as a society? What did the old rituals mean? What if we were to take an anthropological approach to our own predicament?

As we continue to distance ourselves from others in the midst of the new coronavirus pandemic, we hear about other people’s new rituals and routines as we formulate our own. As each day to be spent at home stretches (looms) ahead of us when we awake in the morning, rituals give the day shape, symmetry, a framework. What significance do these new rituals have for us individually and as a society? What did the old rituals mean? What if we were to take an anthropological approach to our own predicament?

Our society needs virologists. Heeding their advice is valuable and consequential. In the Coronavirus pandemic, German politicians listened to the virologists, and Germany is doing relatively well. Other political leaders have (too long) ignored the virologists, and their citizenry is paying a high price.

Our society needs virologists. Heeding their advice is valuable and consequential. In the Coronavirus pandemic, German politicians listened to the virologists, and Germany is doing relatively well. Other political leaders have (too long) ignored the virologists, and their citizenry is paying a high price.