by Michael Klenk

Our society needs virologists. Heeding their advice is valuable and consequential. In the Coronavirus pandemic, German politicians listened to the virologists, and Germany is doing relatively well. Other political leaders have (too long) ignored the virologists, and their citizenry is paying a high price.

Our society needs virologists. Heeding their advice is valuable and consequential. In the Coronavirus pandemic, German politicians listened to the virologists, and Germany is doing relatively well. Other political leaders have (too long) ignored the virologists, and their citizenry is paying a high price.

Put another way; virologists appear to be systemically relevant. That term is central in the current German Coronavirus-debate. Systemically relevant institutions like hospitals, supermarkets, and gasoline stations are less affected by physical distancing measures than (allegedly) ‘systemically irrelevant’ institutions like florists, coiffeurs, theatres, and football competitions.

Talk of systemic relevance may be helpful to organise a society in crisis. It is like societal relevance with a survivalist spin. It implies that, in times of crisis, our ‘society’ shrinks back to a ‘system’ focused on the bottom levels of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs – health, food, and shelter. Societies around the globe have accepted this logic. Pandemic-related restrictions apply more strongly to those not deemed societally relevant, and people (predominantly) complied voluntarily. As an initial reaction to the pandemic, focusing on ‘systemic relevance’ has worked.

However, we can already see that ‘systemic relevance’ gets politicised. For example, lobbyists and interest groups are advocating for increased economic support or lessened Corona-related restrictions for their fosterlings, defending them as systemically relevant institutions. As the initial shocks of the pandemic have abated, as in Germany, people want to get back to normal as soon as possible and the term ‘systemic relevance’ is posed to be a vehicle for them to defend their various interests in the months to come.

Therefore, important debates about systemic relevance and the institutions and professions that make the cut waits around the corner. In the current economic downturn, talks about what institutions to maintain after the crisis (and, therefore, before the next one) may well get heated. For some, like healthcare-, supermarket-, and seasonal workers, whose valuable systemic contribution is now rightly (re-)discovered, increased public affection will hopefully follow.

But institutions and professions that neither contribute to bare necessities, like healthcare nor provide entertainment, like theatres and football clubs, will face more discomforting questions: ‘Why keep them around?’ ‘What will they do for us in the next crisis?’

In particular, the Coronavirus crisis may further accelerate pressures for academics to demonstrate somehow the systemic- or societal relevance of their work to remain funded. Business- or STEM subjects, whose graduates are in high demand with corporations, already prosper. Given the vital contributions of virologists in the current pandemic, societies will likely (and hopefully) continue to appreciate their research.

But the humanities have suffered in recent years. It is therefore good to see that philosophers are also doing their share in pubic discussions of the Coronavirus pandemic. Especially since societies are discussing means to accelerate their way out of the crisis, for example, using a Corona tracking app, philosophers are contributing to the public debate in meaningful ways. Their advice helps politicians and informs the public, just like the advice of virologists. Naturally, philosophical contributions rarely concern the bottom of Maslow’s needs pyramid. Still, they are needed to grasp and ultimately resolve the many value conflicts that arise when we think about responding to the crisis. For example, consider the conflict of privacy vs health in the case of tracking apps. One may thus be hopeful that philosophy will also be appreciated as relevant, and worthy of continued funding, after the crisis.

However, philosophical contributions to the public debate about the crisis mostly seem to communicate externally relevant, but internally bland claims. These claims are relevant in the current public debate, but they often seem uncontroversial within academic philosophy itself. For example, that we ought not to sacrifice some groups in society (e.g. those particularly at risk from the virus) for economic benefits (i.e. getting back to ‘normal’ as soon as possible), or that concerns for privacy ought not to be thrown under the bus for marginally increased utility in a Corona tracking app. These points are important in the public debate. Still, they seem to be active, controversial aspects of current philosophical research only entirely remotely. Partly, this is because philosophical research is, like in virtually all research, increasingly specialised and focused on minute details of an argument. In contrast, public philosophy often seems to concern a ‘bigger picture’ idea.

The situation seems to be different with the virologists. They seem to communicate internally- and externally relevant claims: Findings that concern active issues in their research community and that help society to cope with the pandemic. Those findings are also specialised and concerned with minute details of an argument – what is the actual number of infected people in that German village? – but still they are relevant to the public.

Therefore, we do seem to need active virologists so that they can play their role in the public discourse. But it is less clear that we need active philosophy researchers to communicate philosophical insights on a rather general level to the public. We need a canon of such claims, for sure, and so we depend on having a history in the subject. Still, the case for ongoing philosophical research is less clear.

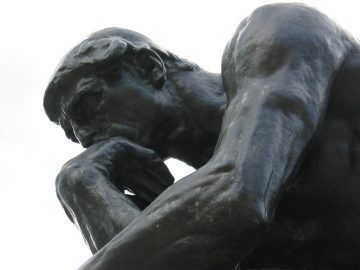

For philosophers like me, this assessment of philosophy’s relevance (if accurate) should be a cause of concern. The Coronavirus pandemic, the focus on systemic relevance, and the likely ramifications for future research funding that I sketched above raise the question of what oneself is contributing to society – as a philosophy researcher. They also point to a lacuna in our current philosophical understanding of the world: What is the value of philosophy, on a systemic or societal level?

As I will argue in my next post, philosophy has done much to help us conceptualise possible answers to these questions. There is nonetheless a rather embarrassing gap in our understanding of what philosophy ultimately contributes.