by Pranab Bardhan

In coping with the dire economic crisis in the wake of the pandemic many developing countries have resorted to cash assistance to the poor for immediate relief. Beyond the relief aspect, many macro-economists have also pointed to the need for such programs to boost mass consumer demand in a period of one of the deepest slumps of general economic activity in many decades. As I have been an advocate for universal basic income (UBI) in poor countries for more than a decade now—my first published paper on the subject came out in India in March 2011 in the Economic and Political Weekly— I have often been asked if the widespread adoption of such cash assistance programs indicates that it is now a propitious time for UBI. While I have supported the cash relief programs in the context of the crisis (most of these programs have not been universal, mainly targeted to the poor) and consider the experience gained in this as generally useful, I think those who like me have supported UBI have usually thought about it in a longer-time framework and in the context of a more ‘normal’ state of the economy with appropriate institutions, political support base, and administrative structures in place. Of course, I’ll not object if in a post-pandemic world attempts are made to help the temporary crisis programs ultimately extend or evolve into a more general UBI program in poor countries.

In coping with the dire economic crisis in the wake of the pandemic many developing countries have resorted to cash assistance to the poor for immediate relief. Beyond the relief aspect, many macro-economists have also pointed to the need for such programs to boost mass consumer demand in a period of one of the deepest slumps of general economic activity in many decades. As I have been an advocate for universal basic income (UBI) in poor countries for more than a decade now—my first published paper on the subject came out in India in March 2011 in the Economic and Political Weekly— I have often been asked if the widespread adoption of such cash assistance programs indicates that it is now a propitious time for UBI. While I have supported the cash relief programs in the context of the crisis (most of these programs have not been universal, mainly targeted to the poor) and consider the experience gained in this as generally useful, I think those who like me have supported UBI have usually thought about it in a longer-time framework and in the context of a more ‘normal’ state of the economy with appropriate institutions, political support base, and administrative structures in place. Of course, I’ll not object if in a post-pandemic world attempts are made to help the temporary crisis programs ultimately extend or evolve into a more general UBI program in poor countries.

A Bit of History

By now it is well-known that the idea of UBI or that of a guaranteed minimum income enabled by a public assistance program has a long history in western thought, going back about 500 years to Thomas More and his friend, Johannes Vives, or that over the years the idea has been supported (and also attacked) by people in the whole range of the political spectrum, by libertarians and socialists alike. On a practical level it has been tried on a large enough scale briefly in the beginning of the last decade in two countries, Iran and Mongolia, and for the last 4 decades in one US state, Alaska. In all these 3 cases the funding source has been the bounty from some natural resource (oil for Iran and Alaska, copper for Mongolia). For rich countries in general, many economists, even in cases when they are otherwise supportive, think that it is much too expensive for the Government to fund a UBI at a decent level. In recent years, however, additional support has come from people (including some from the techno-utopian entrepreneurs of Silicon Valley) who are worried about the work-displacement effects of automation and artificial intelligence in the near future. Inducements for automation may be reinforced if we have to live with the virus for quite some time, as there will then be attempts to avoid production conditions where lots of workers have to congregate.

In this essay I shall primarily talk about developing countries, where more than looming automation there may be some other special factors why UBI may be imperative, and also show that finding resources for a reasonable UBI supplement may be within the realm of fiscal feasibility. Read more »

What does it mean to be white in America in 2020?

What does it mean to be white in America in 2020?

May 26, 2020

May 26, 2020

Have a look at the

Have a look at the  In thinking about knowledge and consciousness, it is just about irresistible to distinguish between the basic facts of what we observe and interpretations or beliefs about those facts. You and I see the same glass of water – maybe our perceptions of the glass are nearly identical – and yet you see it has half full while I see it as half empty. We look at the same economic reports, and you find reason to celebrate while I find cause to worry. We see an artificial satellite in orbit, and you see it an incursion of government and industry into space while I see it as a glory of science and engineering. And so on – it seems obvious that there is a divide between what everyone can plainly see and what’s a matter of interpretation.

In thinking about knowledge and consciousness, it is just about irresistible to distinguish between the basic facts of what we observe and interpretations or beliefs about those facts. You and I see the same glass of water – maybe our perceptions of the glass are nearly identical – and yet you see it has half full while I see it as half empty. We look at the same economic reports, and you find reason to celebrate while I find cause to worry. We see an artificial satellite in orbit, and you see it an incursion of government and industry into space while I see it as a glory of science and engineering. And so on – it seems obvious that there is a divide between what everyone can plainly see and what’s a matter of interpretation.

When I feel myself becoming irritable, disheartened, or just plain fed-up with life during the pandemic, I find it helpful to conduct a thought-experiment familiar to the ancient Stoics. I reflect on how much I have to be grateful for, and how things could be so much worse. That prompts the more general question: Who are the fortunate, and who are the unfortunate at this time?

When I feel myself becoming irritable, disheartened, or just plain fed-up with life during the pandemic, I find it helpful to conduct a thought-experiment familiar to the ancient Stoics. I reflect on how much I have to be grateful for, and how things could be so much worse. That prompts the more general question: Who are the fortunate, and who are the unfortunate at this time?

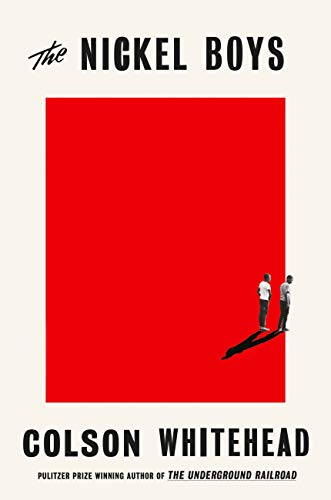

Colson Whitehead won his second Pulitzer Prize for The Nickel Boys in 2020, joining the ranks of three other writers recognized for the rare honor. His first was for another historical fiction The Underground Railroad in 2017. What are the odds of winning the Pulitzer for two books that deal with the same subject – the troubled race relations in America? Pretty good, I would say, if your second book is as brilliant as The Nickel Boys.

Colson Whitehead won his second Pulitzer Prize for The Nickel Boys in 2020, joining the ranks of three other writers recognized for the rare honor. His first was for another historical fiction The Underground Railroad in 2017. What are the odds of winning the Pulitzer for two books that deal with the same subject – the troubled race relations in America? Pretty good, I would say, if your second book is as brilliant as The Nickel Boys.