by Thomas R. Wells

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

I start with the point that erecting statues is a political action and therefore subject to a political logic. Statues are political insofar as erecting them has a cost – not merely the direct costs of building it, but also the opportunity cost of using scarce public space this way rather than another – that only successful political mobilisation can meet. In particular, the more controversial the statue, the more political capital is required to overcome the opposition to its public display, and the more distinctly political must be its logic (in contrast to merely decorative public sculptures that no one much minds). So what is the political pay-off that can justify the political expense of erecting controversial statues? I believe controversial statues are a kind of political communication, a signal to supporters and opponents of the values and people in charge, in which the offensiveness of the message is key to its effectiveness.

Such statues communicate to those on the losing political team. They say, ‘Fuck you. We’re in charge’. To black people in America, the wave of monuments in the 1950s to confederate generals who defended slavery sent two clear messages. Firstly, it sent a message about domination: that the civil rights movement had not and would not change who ruled and in whose interests. Secondly, it sent a message about political values: that this domination was justified by nothing but power and would not be constrained by considerations of justice or the rule of law. Deliberately erecting statues that celebrate odious values shows to the oppressed that moral appeals are hopeless and will not even be heard; that – whatever the new voting laws say – they will never recognised as equals. Read more »

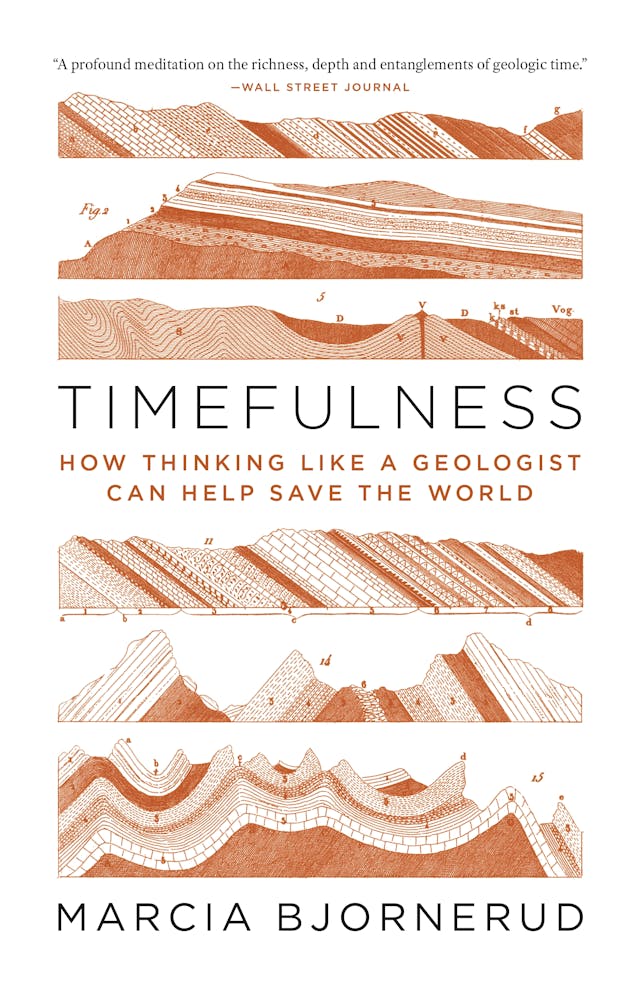

by Paul Braterman

by Paul Braterman

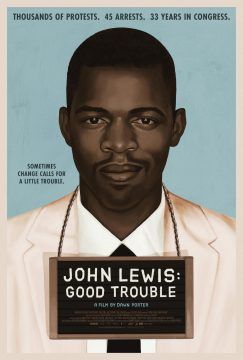

John Lewis: Good Trouble

John Lewis: Good Trouble

The coronavirus pandemic has massively disrupted the working lives of millions of people. For those who have lost their jobs, income, or work-related benefits, this can mean serious hardship and anxiety. For others, it has meant getting used to new routines and methods of working. For all of us, though, it should prompt reflection on how we think about work in general–both as a curse and as a blessing. Here, I want to focus on how work relates to time.

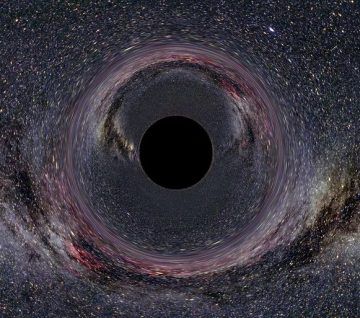

The coronavirus pandemic has massively disrupted the working lives of millions of people. For those who have lost their jobs, income, or work-related benefits, this can mean serious hardship and anxiety. For others, it has meant getting used to new routines and methods of working. For all of us, though, it should prompt reflection on how we think about work in general–both as a curse and as a blessing. Here, I want to focus on how work relates to time. Beauty has long been associated with moments in life that cannot easily be spoken of—what is often called “the ineffable”. When astonished or transfixed by nature, a work or art, or a bottle of wine, words even when finely voiced seem inadequate. Are words destined to fail? Can we not share anything of the experience of beauty? On the one hand, the experience of beauty is private; it is after all my experience not someone else’s. But, on the other hand, we seem to have a great need to share our experiences. Words fail but that doesn’t get us to shut up.

Beauty has long been associated with moments in life that cannot easily be spoken of—what is often called “the ineffable”. When astonished or transfixed by nature, a work or art, or a bottle of wine, words even when finely voiced seem inadequate. Are words destined to fail? Can we not share anything of the experience of beauty? On the one hand, the experience of beauty is private; it is after all my experience not someone else’s. But, on the other hand, we seem to have a great need to share our experiences. Words fail but that doesn’t get us to shut up. In a survey released at the end of May by the AP and the NORC Center for public affairs research, 49% of Americans said they intended to be vaccinated against the new coronavirus, 31% said they were unsure, and 20% said they would not get the vaccine.

In a survey released at the end of May by the AP and the NORC Center for public affairs research, 49% of Americans said they intended to be vaccinated against the new coronavirus, 31% said they were unsure, and 20% said they would not get the vaccine.

Had enough of the 2020 election? Take heart, there are just 134 days left until Vote-If-You-Can Tuesday. That’s less time than it took Napoleon to march his Grande Armée into Russia, win several lightning victories, stall out, and then retreat through the brutal winter, with astronomical casualties, all the while inspiring the equally long

Had enough of the 2020 election? Take heart, there are just 134 days left until Vote-If-You-Can Tuesday. That’s less time than it took Napoleon to march his Grande Armée into Russia, win several lightning victories, stall out, and then retreat through the brutal winter, with astronomical casualties, all the while inspiring the equally long