by Eric Miller

1.

Tell me, what could be more pleasant than to play, in the summertime, a Stone Age re-enactor? A couple of them sat in the flowery grass near a hunebed—a Giant’s Grave or cromlech, some five thousand years old—in the town of Borger, in Drenthe, the Netherlands. The shadow in which this ersatz ancestral couple sat was of the mitigated, oscillatory sort that broadleaf trees in August cast. The year was 2014. Yellowhammers and wagtails called; bulky wood doves reminded me of their Canadian cousins, the passenger pigeons extinct exactly a century before. A puffy dog rested, tufted tail bent round nose, beside the pair who practised some craft proper to their era, I believe it was weaving. The life of a re-enactor at a hunebed cannot be called “pastoral”; it aspires to precede the idea of the pastoral. This idyll took place by the enormous side- and capstones of the megalithic monument I had come to visit. The hunebed, a sort of junior Stonehenge, had the look of a great reptile skeleton; it appeared, though it was inanimate, to enjoy mere basking. Imagine if our bones alone could relish the felicity of life! This is the rude sweetness of nude sunbathing, taken to the posthumous degree: mineral, sparkling.

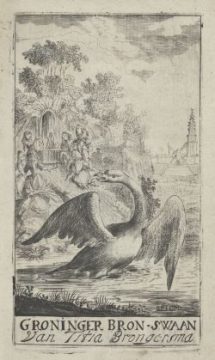

Near the museum attached to the hunebed is a field of stones, boulders really. Glaciers deposited them in this neighbourhood, and the ancient engineers who built the hunebed—archaeologists have named them the Funnel Beaker People—used such granite erratics to build their tombs or temples. In 1685, a poet named Titia Brongersma came to Borger and she directed the first dig at the site. She found articles of funerary pottery; they crumbled at the crisis of their extraction. So much the eloquent guidebook informed me. At that moment, I felt Brongersma call me: in the elusive instant when, having extracted a buried urn, Titia saw it fall to bits in her palms. The act of translation is similarly precarious. Later, I looked for her only book, De bron-swaan, The Swan of the Well. No one had ever rendered more than a few verses from it into English. To write is manual labour, and a kind of re-enacting. Titia used a feather, I am pretty sure. I could sense this quill scraping while I puzzled over her words. I translated them all. Her Swan of the Well makes its reappearance this year.

2.

Sappho reborn! That is what the male intelligentsia of Friesland called the poet Titia Brongersma. In 1686, in the ancient Hanseatic city of Groningen, she published, not without some local éclat, The Swan of the Well. No one knows when she was born, or when she died. I intend to take this opportunity to ponder, briefly, a single song from her book, entitled “De verlangende Tirsis,” “Thyrsis full of longing.” This piece affirms Brongersma’s Sapphic affection for Elisabeth Joly—the poet’s beloved, who appears, in one guise or another, in fully thirty poems. Who was Joly? The historical record is mute. Joly remains no less mysterious than Brongersma herself.

“Thyrsis full of longing” manifests the poet’s mediumistic capacity to preside over a séance of sorts. She makes the sandy Frisian coastline of her verses throng with literary spirits. Quite characteristically, Brongersma adopts a male persona. She tells us what should ring in our ears as we read the piece. She chooses a passage from Jean-Baptiste Lully’s opera Le Triomphe de l’Amour, The Triumph of Love.

Thyrsis full of longing

Air: “Tranquilles coeurs”

I may climb the hills and dunes and gaze

Out on the raving of the hollow seas,

I may pace the beach and scuff the shingle.

But Elise has sailed long since and if she tarried

So much the worse my sorrow would afflict me.

Tears mist my prospect of the shore, the gulf

Might swell with the heaving of my sighs.

The current rips faster, as the tide goes into ebb.

My fear for Elise’s safety is the dart of death.

Her lovely mouth that forms her lovely words,

That place of tender eloquence ruby-tinted!

It makes me raise my arms as though to signal,

The gesture over distance would seize your gaze.

“Can’t you hear me?” I bawl. “Are you as deaf as stone?”

My woe flows back. I would fall from delusion’s

Cliff-top, unless you rode a wingèd dolphin’s back

Plotting a course to me, over water.

Let me be the coastal beacon never dim

Inextinguishably kindling your kindly mind.

The bonds that chafe me only you can loose,

My heart’s consolatory Palinurus.

3.

Brongersma’s title all by itself artfully conjures a ghost. “Thyrsis” is a pregnant name. It figures in the Roman poet Vergil’s Eclogues. A pastoral allusion, therefore: a matter of love in idleness, of shepherds, of shepherdesses. But Brongersma is a poet of uncanny implication. When we consult Vergil, we discover several particulars about Thyrsis. He resides in Arcadia, of course, not in Frisia. He enters a mighty song-contest. In the course of his performance, he describes his amatory predicament. He complains he counts to his lover “less than seaweed thrown up ashore” (projecta vilior alga). As her reader learns, Brongersma’s Thyrsis stands on an actual North Sea beach where much such unvalued seaweed must clump at his feet, bedraggled. Vergil’s wretched anti-hero loses his song competition. Brongersma, sketching an amitié with the fickle Elise—Elisabeth Joly’s skittish avatar—plays rapturously, ironically, with ideas of winning and failing, the wager and danger of love.

It is time to consider the tune to which Brongersma directs her “Thyrsis, full of longing” should be set. The French libretto intensifies the maritime, amorous resonances already lightly instinct in the name “Thyrsis.” I have said they come from Jean-Baptiste Lully’s opera Le Triomphe de l’Amour. In this work, the gods and goddesses of Greece and Rome must capitulate, one after the other, to the rule of Venus. Brongersma snatches her tag from the opening lines of the opera. Let me translate:

Carefree hearts, arm yourselves

For a thousand secret alarms.

You will forfeit the repose so sweet

Which you cherish deeply for its charms.

But love’s frisson is hundredfold more

Appealing than peace at its sweetest.

Venus famously rose from the bosom of the sea. Brongersma’s Thyrsis aptly stands at the ocean’s erotic brink. In Lully’s opera, Neptune woos Amphitrite. Next Bacchus, discovering Ariadne forsaken by Theseus and slumbering on the beach of Naxos, takes her to wife. A proud Frisian, Brongersma accommodates the loves of the gods—as well as French artistic fashion—to her native shore and her private passion, Elisabeth Joly.

4.

“Can’t you hear me?” bawls Thyrsis, “Are you as deaf as stone?” Elise may not hear Thyrsis, but ghosts congregate at Brongersma’s summons. Her unfortunate speaker continues:

My woe flows back. I would pitch from delusion’s

Cliff-top, unless you rode a wingèd dolphin’s back

Plotting a course to me, over water.

With these words, another pair of shades, both Greek, surge like breakers to assist the articulation of Thyrsis’s grievances.

Thyrsis’s temptation to jump to his death recalls a legend associated with the original Sappho herself. After the ferryman Phaon jilted her, some say she took her own life. Ovid versifies this unlikely story. A nymph urges Sappho to hurl herself off a lover’s leap into the Aegean: “Seek steep Leucada, and do not shrink from its edge.” Frisian luminaries joined in chorus in 1686 to call Titia Brongersma a Sappho reborn. Brongersma’s dalliance with Sapphic allusion is in keeping with the tendency of their praise.

Luckily, the buoyant image of a dolphin piloted by Elise negates the dire idea of suicide. This vision rescues Brongersma’s speaker from his despair. Elsewhere among her poems—in verses addressed to Johan Jacob Monter—Brongersma alludes directly to a relevant myth, Arion’s.

Like Sappho a native of Lesbos, the musician Arion once booked passage from Corinth. That great city had lavished riches on him, and fame. Now he was going back to the island of his birth. The crew of the ship on which he sailed, eager to rob him, ganged up to toss him overboard. Celebrated for inventing the dithyramb, Arion begged the indulgence of a last musical performance. We may call it in Brongersma’s context an ironic swansong. For Arion’s music called to the ship’s side a dolphin—much as Brongersma recruits to Thyrsis’s lament all the glamour of literary allusion—and the musician, far from drowning, rode the amiable creature to the port of Taenarus. There the ruler Periander had the guilty sailors crucified.

Brongersma probably knows, too, that Arion was famous for his hymn to Neptune, a god well disposed to dolphins. Her miraculous sea-beast would ferry Elise, not Thyrsis. Here Brongersma’s music, like Arion’s, casts a spell intended to attract the help of an embodied salvation.

6.

More fraught is the last allusion Brongersma makes. Her Thyrsis calls Elise his “heart’s consolatory Palinurus.” The story of Palinurus’s death and Aeneas’s meeting with him in the underworld are, together, two of the most haunting episodes in Vergil’s epic Aeneid. Talk about ghosts! At the end of Book 5, Neptune sends Somnus, Sleep, to stupefy Palinurus, the helmsman of Aeneas’s flagship. Palinurus is a human sacrifice, though neither Aeneas nor any of his crewmen know it. Somnus anoints the pilot’s temples with a bough dipped in Lethe, the river of forgetfulness. Thus drugged, Palinurus falls into the sea. Aeneas, discovering the loss of his helmsman, blames the victim for nodding off. The hero laments, “You will sprawl naked, Palinurus, on ignominious sand” (Nudus in ignota, Palinure, iacebis arena). Brongersma’s Thyrsis stands on a beach; he avows his naked heart; he implies he has steered through his life by Elise’s direction, consulting her as Palinurus consulted the stars.

Descending to the underworld, Aeneas encounters the ghost of Palinurus. The dead man protests that proper burial rites have not consecrated his corpse. He asks Aeneas to carry him across Styx, so that he may at last find rest on the farther shore. The hero replies that he cannot fulfill this request. Yet Aeneas offers some solace. He will honour Palinurus’s bones with a grave-mound:

And they will raise a barrow, and they

Will perform your final rites and the place

Will preserve your name, forever.

Et statuent tumulum, et tumulo solemnia mittent,

Aeternumque locus Palinuri nomen habebit.

Aeneas’s promise came true. The Punta di Palinuro retains to this day the helmsman’s name.

Allow me to draw an analogy. Taking up a brave station in the history of literature and on a seventeenth-century beach, Brongersma dares to perpetuate her elegiac devotion to the alluring Elise. By her verbal magic, the North Sea dunes of “Thyrsis full of longing” become, before our eyes, a monument as perennial as Palinurus’s.

A monument ends by memorializing, in some measure, everyone who reflects on it. Six years ago, I was happy—blithe might be a better word—to inspect the hunebed at Borger. Titia Brongersma says she wept, however, when in 1685 she handled the relics she removed, a pioneer of archaeology, from inside the same monument. She could not revive the dead. But she could imagine them:

It is as good as kisses from many lips

That your earthen worth is now extolled.

I felt for you, salt tears thickly coursing,

Soaking through your opening to the bottom

Where remains lay packed in you, while I kneeled

In front of you, the crumbly stuff sifting

From the burst seal burial long sanctified.

Brongersma nobly plays the part of a re-enactor—the re-enactor of Stone Age grief. This is, to borrow a phrase from Lully’s opera, a triumph of love.

As Brongersma’s translator, I am her celebrant as well as her mourner. Unlike Charon—or a wingèd dolphin—I cannot ferry the poet or Elisabeth Joly, either, back across the waters of oblivion. Like Vergil, however, I can do my best to renew a worth that now is earthen. The Swan of the Well turns out to be a kind of phoenix. We may not know where Brongersma’s tomb is—no hunebed marks it—but I am pleased to believe that the spirit of her verse, appeased, vitalized, can live again on our lips.