by Alexander C. Kafka

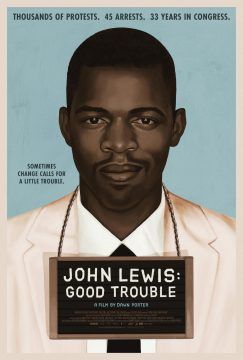

John Lewis: Good Trouble couldn’t be more timely.

John Lewis: Good Trouble couldn’t be more timely.

The new documentary, which will be available Friday on demand, arrives amid Black Lives Matter protests and renewed and deepening threats to the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It shows one of the architects and key drivers of that legislation, the longtime civil-rights activist and congressman from Georgia, in both his soft-spoken private sphere and in his amiable but passionate public life. As he despairs over a democracy in peril, both his sadness and his hope resonate profoundly, even as the 80-year-old widower battles stage-four pancreatic cancer.

The film avoids his illness, as it does health details around his wife Lilian’s death in 2012. I wish it dealt more forthrightly with Lewis’s cancer, because a reminder of his mortality would underline how fragile is the progress he has helped bring about. It is too tempting to take this icon and his life’s work for granted.

What shines through in the film, directed with unobtrusive clarity and empathy by Dawn Porter, is Lewis’s fundamental kindness and gentleness. There is one key exception: a low-blow tactic he used against his close friend Julian Bond when they were pitted against each other in Lewis’s first congressional race in the 80s.

Lewis is down to earth, funny, and charismatic. Pulling his roller bag through Reagan Airport to a flight becomes a foot-by-foot meet and greet. Porter shows Lewis surrounded by large screens on a set at Arena Stage watching his life pass before him, literally, in news footage. Seeing the older Lewis witness the younger Lewis speaking at the 1963 March on Washington, or with his head still bandaged after the fury of cops’ batons, gives a profound sense of his expansive experience and achievements.

The nonviolent protester, though often bloodied, has never been bowed, and as he transitioned to representative politics he has remained, first and foremost, a savvy and tireless tactician with his eye on the long game, whether the topic was voting rights, job training, day-care subsidies, fair housing, gun control, ending the death penalty, raising the minimum wage, repealing Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, passing the Affordable Care Act, or protecting victims of domestic violence. It is for good reason that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and others call him “the conscience of the Congress.”

The son of Troy, Alabama, sharecroppers, he was a born preacher. As we learn in an oft-repeated stump-speech ice breaker, the young Lewis gathered the farm chickens around him to sermonize to them. He reached out to his hero Martin Luther King Jr., who called him “the boy from Troy.” His skull cracked open by Alabama state troopers on the Pettus Bridge in Selma, roughed up again in lunch-counter sit-ins in Nashville and on Freedom Rides to desegregate bus stations, Lewis explains that he simply gave up fear.

His gains were crucial to the election of the first Black president — Barack Obama said as much to him in autographs after the president’s first and second inaugurations. Lewis also fostered the growth of an increasingly vibrant Black caucus. But the film focuses most of all on Lewis’s work — in bipartisan coordination with colleagues across the aisle like Jim Sensenbrenner of Wisconsin — to protect voting rights, which are in dire jeopardy.

Paul Weyrich, the New Right political strategist, says: “They want everybody to vote. I don’t want everybody to vote. Elections are not won by a majority of the people, they never have been since the beginning of our country, and they are not now. As a matter of fact, our leverage in the elections, quite candidly, goes up as the voting populous goes down.”

The Voting Rights Act was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, and extended by Presidents Richard M. Nixon, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and George W. Bush. But by 2011, voter suppression was on the rise, especially in the South, through photo ID requirements, cuts to early voting, and obstacles to registration. The Supreme Court case Shelby County v. Holder, in 2013, gutted a key provision requiring states with histories of voter suppression to get changes in voting rules pre-approved by the federal government.

In 2016, courts ruled that discriminatory restrictions be removed in North Carolina, Kansas, North Dakota, and Texas, but a number of states still have restrictive laws on the books. Amid Covid-19, recent voting chaos and long lines in Wisconsin and Georgia made clear the urgency of ballot by mail come November. The Trump administration, however, is doing its best to discredit mail-in balloting with ill-founded fear mongering about fraud, and the Supreme Court, just last week, sided with Texas in blocking expansion of votes by mail. Trump is trying to extinguish the U.S. Postal Service entirely.

In the wake of thousands of polling sites closed, millions of people removed from voting rolls, and voting restrictions unseen since Reconstruction, a downcast Lewis tells colleagues: “Today I come with a heavy heart, deeply concerned about the future of our democracy. People have a right to know whether they can put their faith and trust in the outcome of our elections.”

“Our democracy is under attack,” Eric Holder, attorney general under Obama, says. “And it’s under attack in a way we have not seen for 50 years.”

“Some of those old battles that many of us thought had been fought and won,” he says, “we have to re-engage. This is not a time for despair. This is a time for action. That’s what I learned from John Lewis.”

That’s what you too will come away with from this moving documentary portrait. Don’t be fooled by Lewis’s friendly demeanor or the fact that a cute, goofy little dance he did in his office to Pharrell Williams’s “Happy” went viral. He urges us to engage in “good trouble, necessary trouble,” and reminds us that he’s been arrested 45 times — five of those since he was elected to Congress.

He is a lion.