by Samia Altaf

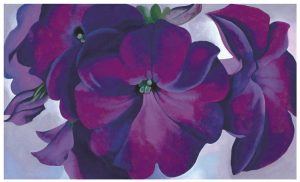

“Let’s go look at the flowers outside,” I say, as I sense Dad sinking into the recesses of his fading memory. I wheel him out. Look at the petunias. What a riot—purple, pink, white, that ordinary pedestrian flower in such abundant glory. I hold a bunch to his nose and he takes a deep breath. “Wow,” he says, and opens his eyes. The misty and faraway look hits me hard. It is like looking inside a bombed-out building that has few windows left intact and very little light. But he tries, never having been one to give up; he blinks shortsightedly at the greenery, the flowers, and the blue sky, and shakes his head at the wonder of it all—and of him being there in the middle of it. He struggles to say something but gives up halfway—words too have faded. “Wow,” he says again.

Dad has steadily and imperceptibly lost all memory to Alzheimer’s. Memories of his children, friends, family, his wife now gone. Only shards of crystallized knowledge—encoded so deeply—remain beyond the cognitive deterioration, He recognizes the simple beauty of flowers, they are still real. We look at the yellow rose bush, the petunias and the marigolds, this lovely spring evening. His face lights up. “Wow,” he says, over and over. And then: “I have these in my house” and “when will I go there?” He asks, a complete sentence, and looks anxiously at me, his brow scrunched with a look fit to break your heart. That he remembers—his house and the feeling of wanting to go there. One he had to leave when he and mom got to be too sick to live on their own. Do memories plague his ears, like flies?

“Do memories plague their ears like flies?

They shake their heads. Dusk brims the shadows.

Summer by summer all stole away,

The starting gates, the crowds and cries.”

(Philip Larkin)

Till recently, he seemed to be plodding along, still teasing his wife, picking food off her plate or commenting on her hair, still dark and abundant at 85, and telling her they will go home soon. The change came imperceptibly and slowly. “Memory loss is the key symptom of Alzheimer’s disease. An early sign of the disease is usually difficulty remembering recent events or conversations. As the disease progresses, memory impairments worsen and other symptoms develop. At first, a person with Alzheimer’s disease may be aware of having difficulty with remembering things and organizing thoughts.”

I push him around the perimeter of the yard towards the gate leading to the street. He looks out at the street children playing cricket with wooden paddles, at their squabbles, and laughs. He sits up, looks hopefully at me—“Are we going home?” My usual strategy with him is to go along on whichever pathway he finds himself. Sometimes it is difficult. But I do not want to lie, and worried he might get stuck in this loop, I try and distract him with newly-emerging sweet peas, so delicate, so vivid, their tendrils clinging precariously to the cane stalks—much like my own hold on things. He nods without looking at them. I’m losing him, I can tell. “Let’s go in,” I say, and turn his wheelchair around to face the house, his daughter’s, and one he has lived in for the past six years, four with his wife, two without her. He sits in the wheelchair looking at the house.

“Wow.” He says taking a deep breath,“Beautiful house, who lives here?” “You do,” I tell him, “with your daughter and her family.” He looks at me as if he has not heard a word. “You have been living in this house for six years now,” I say in a cheery voice, hoping to jog his memory, careful to filter out any sadness, as if this was the most normal question for him to ask.

Although he sank into this state slowly and steadily, and I know what Alzheimer’s looks like—the moth-eaten hemispheres unevenly scarred—I fail to understand how his mind feels, how it might work. “Neurons are damaged, lose connections to each other and eventually die.” But his eyes can see the beauty of flowers and hear children’s voices. Some remnant of the optical pathway is still intact. For how long? He shakes his dear head, now shiny and bald over the damaged hemispheres. Cheeks glowing, he mutters, “Wow,” breathing deeply of a hot pink rose.

At times it seems if he could look at flowers and children he would get through it all. When he was well, he was interested in everything that happened around him and to everyone around him—the weather, food, people, politics, poetry books. He’d ask you questions, wanting to hear your “story,” not tiring of the same one every day. “So, where did you go?” “Just to my job.” “Ah! And then? What did you do?” “Just my work.” “How nice! What did you eat for lunch…” A sandwich. “What kind? was it good?” Such ordinary doings gave him such extraordinary delight for they had to do with his children’s life. He’d hear them again and again, and forgive you when you mangled some detail in the retelling, delighting in the tangent, working it into the original narrative—looking triumphantly at mom—who, being a woman of few words, just shook her head eternally baffled by this tendency.

I understand Dad wanting to go “home.” I understand about one’s own home. The metaphorical and the literal home. The physical place and the one in the mind. Some say it is a feeling, but feelings are important. Lawrence Durrell wrote in Spirit of Place, “It is there if you just close your eyes and breathe softly through your nose; you will hear the whispered message, for all landscapes ask the same question in the same whisper. ‘I am watching you—are you watching yourself in me?’”

I suppose both are important. I too have struggled with this feeling all my life—of wanting to go home. But where is home for me? Living in the US and in Pakistan, at home in both, yet, at times, in neither. About wanting to have a permanent home with one’s own things sitting in it—dusty, outmoded, scarred maybe, but happy to see you when you come, nodding to you from familiar dark corners. And overwhelmed by life, needing the security of being amongst familiar things, knowing deep down that all will be well, once I am in my own home,amongst my own things. The old knitted blanket, pearl white when it started decades ago, and now quite grey. My mother and I made it together when she taught me how to knit. The patchwork bedspread, my grandmother’s, my dad’s poetry books, the edges tattered. O to eat off one of the five dinner plates –all that remains of the ink-blue, Wedgwood twelve-place dinner set—one that was part of my mother’s dowry. I ride this feeling constantly. Every time I sit in a plane across the Atlantic I feel disoriented. Am I going home or away from home? The thought always pushed back by the urgency of tasks to be done. Sick father, sick mother, handicapped brother, and a sister in trouble—all clamoring for attention, persistent and urgent. And one’s own life needing to be lived, with some things more urgent than others. It seems there never was time or world enough. And now it seems just too much. And yet.

He lets drop the petunias he had been holding on to, clasps tight the arms of his wheelchair. “I want to go home,” he says, looking up at me, with that look.

“I know that feeling, Dad,” I say, wheeling him inside.