by Jeroen Bouterse

Rutger Bregman’s Humankind: A Hopeful History is a clearly written argument if ever there was one. Bregman believes humans are a kind species and that we should arrange society accordingly. The reason why this thesis needs intellectual support at all is not that it is particularly profound or complicated, but that there are so many misunderstandings to be cleared away, so many apparent objections that need to be overcome.

Rutger Bregman’s Humankind: A Hopeful History is a clearly written argument if ever there was one. Bregman believes humans are a kind species and that we should arrange society accordingly. The reason why this thesis needs intellectual support at all is not that it is particularly profound or complicated, but that there are so many misunderstandings to be cleared away, so many apparent objections that need to be overcome.

You have already thought of those objections, or you will if you take half a minute. Bregman confronts many of them squarely. He looks at historical atrocities, social-psychological experiments such as the Stanford prison experiment, and famous anecdotes about human cruelty or indifference, patiently explaining how we should look at these in a different light. The anecdotes turn out to be less damning to human nature, and the experiments more flawed than common perception has it.

Of course, this leaves, well, human history. Bregman is aware that his beloved humans have committed all kinds of horrific acts of violence over the millennia. This is a problem for his thesis, and it remains one. Though the book does present an attempt to explain all the violence in a way that lets human nature off the hook, I do not think that this attempt is satisfactory. Read more »

Anguilla is a sandbar ten miles long. It’s three miles wide if you’re being generous, but generous isn’t a word that pairs well with the endowments of a small, arid skerry of sand pocked with salt ponds.

Anguilla is a sandbar ten miles long. It’s three miles wide if you’re being generous, but generous isn’t a word that pairs well with the endowments of a small, arid skerry of sand pocked with salt ponds.

Physics writing, let’s face it, is usually pretty boring. In a recent

Physics writing, let’s face it, is usually pretty boring. In a recent

I have a friend who is a self-described “cop magnet.” He’s been arrested six or seven times, just standing there.

I have a friend who is a self-described “cop magnet.” He’s been arrested six or seven times, just standing there.

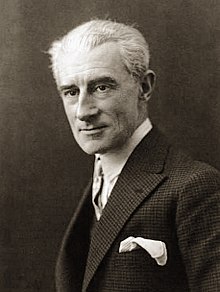

Lately I’ve been craving the music of French composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). As reality continues to be fraught, in the midst of a pandemic, social unrest, culture wars, and on and on, Ravel’s music offers an enticing escape. Described by his close friend, concert pianist Ricardo Viñes, as “inclined by temperament toward the poetic and fanciful,” Ravel created music that continues to captivate with its otherworldly beauty. Another reason for his appeal now, when the public health crisis has disrupted all of our quotidian rhythms, is that rhythm is the sine qua non of Ravel’s art. All you have to do is listen to

Lately I’ve been craving the music of French composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). As reality continues to be fraught, in the midst of a pandemic, social unrest, culture wars, and on and on, Ravel’s music offers an enticing escape. Described by his close friend, concert pianist Ricardo Viñes, as “inclined by temperament toward the poetic and fanciful,” Ravel created music that continues to captivate with its otherworldly beauty. Another reason for his appeal now, when the public health crisis has disrupted all of our quotidian rhythms, is that rhythm is the sine qua non of Ravel’s art. All you have to do is listen to

Being Korean is a behavioral science all its own. There are formalities at all levels of society and potential affronts lurking in every social engagement. Ageism is set in stone, and in honorifics that define older or younger persons, friends, siblings and relatives, as well as differing levels of social standing. Personal humiliations are many and varied, some of them universally recognizable, some of them exclusive to Korea’s tight-knit family structures or evident hierarchies. It goes beyond how to address someone: How to drink soju, how to pour it for a superior, how to bow, when to bow, who to bow to, when to get down on your knees—the list goes on.

Being Korean is a behavioral science all its own. There are formalities at all levels of society and potential affronts lurking in every social engagement. Ageism is set in stone, and in honorifics that define older or younger persons, friends, siblings and relatives, as well as differing levels of social standing. Personal humiliations are many and varied, some of them universally recognizable, some of them exclusive to Korea’s tight-knit family structures or evident hierarchies. It goes beyond how to address someone: How to drink soju, how to pour it for a superior, how to bow, when to bow, who to bow to, when to get down on your knees—the list goes on. Jeanine Cummins’ American Dirt is a string pulled so tightly it is on the verge, always, of snapping. It is like this from the first sentence, when our protagonist Lydia Quixano Alvarez’s 8-year-old son, Luca, finds himself in a rain of bullets while he uses the bathroom. By the second page, sixteen members of Lydia and Luca’s family are dead, murdered by the reigning drug cartel of Acapulco, Mexico.

Jeanine Cummins’ American Dirt is a string pulled so tightly it is on the verge, always, of snapping. It is like this from the first sentence, when our protagonist Lydia Quixano Alvarez’s 8-year-old son, Luca, finds himself in a rain of bullets while he uses the bathroom. By the second page, sixteen members of Lydia and Luca’s family are dead, murdered by the reigning drug cartel of Acapulco, Mexico. The language of light is compelling. The suggestions of light at daybreak are vastly different from twilight or starlight, the light of a firefly is not the same as that of embers or cat eyes, and light through a sapphire ring or a stained glass window is not the same as light through the red siren of an emergency vehicle or through rice-paper lanterns at a festival. It matters to writers if the image they are crafting of light is flickering or glowing, glaring or fading, shimmering or dappled. A writer friend once commented on light as a recurring motif in my poetry, and told me that I’d enjoy her son’s work as a light-artist for theater. The thought struck me that light in a theater has a great hypnotic, silent power; it commands and manipulates not only where the audience’s attention must be held or shifted, how much of the scene is to be revealed or concealed, but also negotiates the many emotive subtleties and changes of mood. The same goes for cinema, photography, and other visual arts. Light almost always accompanies meaning.

The language of light is compelling. The suggestions of light at daybreak are vastly different from twilight or starlight, the light of a firefly is not the same as that of embers or cat eyes, and light through a sapphire ring or a stained glass window is not the same as light through the red siren of an emergency vehicle or through rice-paper lanterns at a festival. It matters to writers if the image they are crafting of light is flickering or glowing, glaring or fading, shimmering or dappled. A writer friend once commented on light as a recurring motif in my poetry, and told me that I’d enjoy her son’s work as a light-artist for theater. The thought struck me that light in a theater has a great hypnotic, silent power; it commands and manipulates not only where the audience’s attention must be held or shifted, how much of the scene is to be revealed or concealed, but also negotiates the many emotive subtleties and changes of mood. The same goes for cinema, photography, and other visual arts. Light almost always accompanies meaning.