by Anitra Pavlico

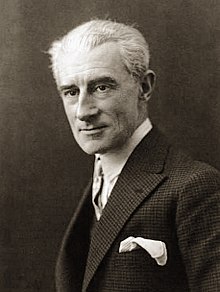

Lately I’ve been craving the music of French composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). As reality continues to be fraught, in the midst of a pandemic, social unrest, culture wars, and on and on, Ravel’s music offers an enticing escape. Described by his close friend, concert pianist Ricardo Viñes, as “inclined by temperament toward the poetic and fanciful,” Ravel created music that continues to captivate with its otherworldly beauty. Another reason for his appeal now, when the public health crisis has disrupted all of our quotidian rhythms, is that rhythm is the sine qua non of Ravel’s art. All you have to do is listen to Bolero, for which he is best known, to perceive this on a visceral level. And yet Ravel is much more than Bolero, as he would have been the first to tell you. He considered that piece more of an experiment or a gageure–a wager with himself that he could turn one musical phrase into an orchestral composition, and he referred to it as “orchestral tissue without music.” It consists of one main theme that is repeated and embellished throughout. Its genius lies in the orchestration. Ravel’s skills as an orchestrator, his devotion to rhythm, and his “passion for perfection,” in the words of biographer Madeleine Goss, are his enduring legacies.

Lately I’ve been craving the music of French composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). As reality continues to be fraught, in the midst of a pandemic, social unrest, culture wars, and on and on, Ravel’s music offers an enticing escape. Described by his close friend, concert pianist Ricardo Viñes, as “inclined by temperament toward the poetic and fanciful,” Ravel created music that continues to captivate with its otherworldly beauty. Another reason for his appeal now, when the public health crisis has disrupted all of our quotidian rhythms, is that rhythm is the sine qua non of Ravel’s art. All you have to do is listen to Bolero, for which he is best known, to perceive this on a visceral level. And yet Ravel is much more than Bolero, as he would have been the first to tell you. He considered that piece more of an experiment or a gageure–a wager with himself that he could turn one musical phrase into an orchestral composition, and he referred to it as “orchestral tissue without music.” It consists of one main theme that is repeated and embellished throughout. Its genius lies in the orchestration. Ravel’s skills as an orchestrator, his devotion to rhythm, and his “passion for perfection,” in the words of biographer Madeleine Goss, are his enduring legacies.

Goss’s biography, Bolero: The Life of Maurice Ravel (Holt and Company, 1945), while a friendly portrayal, nonetheless gives a helpful overview of the main events in Ravel’s life and of the evolution of his art. Ravel lived in Paris from a few months of age, but he returned to the place of his mother’s birth, Ciboure, on the Basque coast, every summer. Young Maurice loved the fête days in Ciboure, when the townspeople would make music and dance the fandango. Goss credits this experience with inspiring a lifelong love for rhythm in Ravel. Igor Stravinsky referred to his friend as “the Swiss clockmaker of music.” Ravel’s father, Joseph, was also musically inclined, having studied piano and won awards at the Conservatory in Geneva, but he was also gifted in mechanics and in inventing machinery, and decided to pursue engineering. [1] Maurice was fascinated by the orchestra and all of its moving parts, and appears to have inherited his father’s gifts in engineering and applied them to composing music. Combined with the methodical approach of the engineer is Ravel’s lifelong affinity for folklore and fairy tales. The mixture of these different sources of inspiration makes for a world unto itself, driven by desires for harmonic innovation, rhythm, and escape.

The Paris of Ravel’s time is of course famous for having been a hotbed of artistic activity. Ravel allied himself with other young artists who rebelled against convention for convention’s sake. Yet while always chasing new harmonic combinations and new ways to utilize instruments, especially the piano, he never discarded the traditions of the past as composers such as Arnold Schoenberg did. Ravel felt that Schoenberg’s music was overly complicated and that his musical reasoning was necessarily limited. He believed that music in the future would return to melody rather than go further down the road of atonality. Ravel admired Mozart (“a god”) above all other composers, and never embraced the dissonance or general iconoclasm that certain other early 20th century composers did. His contemporary, the poet Tristan Klingsor, said: “It is almost unbelievable that the academicians did not understand how classical he really was–classical in his desire for order in all things, in the placing of his periods, in the melodic design, in harmony, in instrumentation. When he innovated, and certainly as harmonist he did this frequently, it was in drawing unexpected but logical consequences from old principles.”

Nonetheless, new sounds were very much the holy grail for Ravel and his cohorts. At the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1889, Ravel was struck by the novelty of Russian composers such as Rimsky-Korsakov, whose music was not widely known in Paris at the time. Ravel and others, notably Claude Debussy, were also taken by the sounds emanating from the Javanese “orchestra” at the Exposition–the gamelan, made up largely of a number of metallic percussion instruments that the players strike with mallets. Other French composers that influenced Ravel include Emmanuel Chabrier and Erik Satie. Ravel discovered Chabrier’s music in 1890, and considered it a prime example of “vivid, effective musical speech,” as Goss puts it. Ravel credited Chabrier with having inspired his Pavane pour une Infante Défunte, one of his first compositions to garner attention. As for Satie, Ravel said he never tired of studying and playing his music. Gabriel Fauré, who taught advanced composition at the Paris Conservatory, where Ravel studied through the 1890s, was also an enormous influence. Ravel later dedicated his Jeux d’Eau and String Quartet to Fauré. He admired Fauré’s lyricism and emotional restraint, two qualities that also came to characterize Ravel’s work. Ravel was also impressed by Stravinsky’s orchestration abilities.

Ravel had early setbacks, including the critics’ panning of his Shéhérezade song suite set to poems of Klingsor; according to Ravel’s brother Edouard, Maurice considered Shéhérezade one of his best compositions. Ravel also failed to win the prestigious Prix de Rome: the ensuing controversy over the chasm between those who thought he deserved the award and those who thought he was too radical led to the “affaire Ravel” and the resignation of the director of the Conservatory. Ravel remained dedicated to his work and was outwardly detached; his music in due course began to achieve widespread acclaim. Jeux d’Eau was hailed for its new technique for the piano. Ravel said he was “inspirée du bruit de l’eau,” and this work was the first to achieve this sound on the piano. His String Quartet, composed in 1904, was also called a masterpiece.

Goss portrays Ravel as a somewhat aloof, mysterious man who nonetheless had a deep capacity for feeling and warm regard for those to whom he was close. He was never linked with anyone romantically, woman or man, although a more recent biographer has made the case that Ravel was a homosexual. Most agree, however, that Ravel’s personal life was a mystery. He seems to have redirected what might have been romantic passion into creating music: as he himself said, “I think and feel in music.” He had many close friends, especially those in the self-styled “Société des Apaches”–an ironic title based on an epithet that a gruff pedestrian hurled at Ravel and Viñes on a Paris street one night. “Apache,” after a group in the Parisian underworld, was meant to be a pejorative term for an outcast who had no regard for societal laws and norms. Ravel and Viñes took it as a compliment. Other Apaches included young writers, painters, and musicians who gathered at the home of a painter and musician named Paul Sordes, who lived in the rue Dulong, above Montmartre. These artists shared a craving for innovation and a disdain for convention. Among many other interests, they shared a fascination with Russian music and listened to anything they could find: Rimsky-Korsakov, Mussorgsky, Borodin. Ravel was widely known as someone who shunned the spotlight–“indifferent alike to praise and to censure, [he] thought only of escaping from both,” Goss writes. His indifference may be overstated here: Ravel, partly due to the affaire Ravel, and partly due to simple pride (as he later admitted), refused the Legion of Honor three times. While he was very much a Parisian, many maintain that his sensibilities were largely formed by his Basque heritage–close to Spain, part of France, yet unto themselves, the Basque people are characterized by a mix of emotional warmth and reserved restraint. Goss writes that Ravel was marked by “elegant indifference, [and a] horror of triviality and all effusions of sentiment.”

While it may be hard to see how rhythm plays more of a role in Ravel’s music than in other composers’–I don’t know of any musician who is not guided by a sense of rhythm–it is evident that Ravel’s work is more conducive to dance than that of other composers. This may in fact be due to the impact that the Basque fêtes had on him from an early age, as Goss suggests, or it may have been a particularly fertile period for ballet, or a combination of both. Ravel’s year for ballet was 1912. Sergei Diaghilev of the Ballets Russes asked Ravel in 1910 to write a ballet on the Greek legend of Daphnis and Chloe, which the Ballets Russes performed in 1912. Along with Daphnis et Chloé, Ravel’s ballets Adélaïde, ou le langage des fleur and Ma Mère l’Oye also premiered in 1912. All were very well received.

Ravel’s later years were marked by tragedy. Despite his immersion in his work, he was also very patriotic and longed to enlist in the war effort after France entered World War I, over the strenuous objections of family and friends. Never a physically robust specimen–he measured a diminutive 5’3″–he was refused by the authorities. Undeterred, he went on to volunteer to care for wounded soldiers at the hospitals in Biarritz. He was eventually accepted to be a truck driver and left for the front in March 1916. In letters home he describes himself as “curious for adventure” but admits that “I have never been brave.” The experience was physically and morally devastating for him. He fell ill, spending a few weeks in a hospital near the front then returning to Paris to convalesce. The death of his mother around this time, with whom he had lived for his whole life, hit him hard. After the war and his mother’s death Ravel fell into a depression. When he was able to begin working again, he composed Le Tombeau de Couperin as a tribute to friends he lost in the war. Light and graceful on the surface, there are undertones of suffering and vulnerability not always found in Ravel’s other compositions.

Ravel’s life took a serious downturn after he was involved in a minor taxi accident in Paris in 1932. It is thought that the blow to the head that he suffered may have exacerbated an underlying brain condition. Within a year of the accident he began exhibiting symptoms of aphasia. Ravel became bitterly unhappy at his utter inability to express the abundance of musical ideas in his mind. He never recovered from a surgery performed in late 1937, and passed away ten days later.

Ravel’s music imprinted itself on me at an early age. One of the first classical pieces I recall hearing was his Pavane at age three or four. I subsequently went a number of years without hearing it, and when I heard it again while in college the emotional effect of this musical déja vu was nearly heart-stopping. Another piece I recall loving as a child was Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, originally a piano piece that made little impact. After Mussorgsky’s untimely death at age 42, Ravel orchestrated the piece in his usual masterful fashion, and it is a favorite among classical listeners. Other particular favorites of mine are his Gaspard de la Nuit for piano–wickedly difficult to play and diabolically beautiful. I love this performance by Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli. Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G (especially the exquisite second movement) and Rhapsodie Espagnole are also indispensable.

French composer and pianist Henri Gil-Marchex has written that Ravel’s scores are “always admirably clear.” The composer took pains to give extensive indications to the performer on how to realize the composer’s intent. This is no doubt part of the passion for perfection noted by Goss. Gil-Marchex adds that “the poetic interpretation is most subtle, and the effort of imagination necessary to translate Ravel’s thought is far beyond the ability of ordinary players. . . . It is music to be played with the heart, but also with clear intelligence.” I hope you have enjoyed this diversion from reality into the heart and intelligence of Ravel. If you’re anything like me, you won’t want to come back.

[1] Joseph went on to invent a car that could perform somersaults, a trick called the saut-de-mort, or jump of death. The car was used in Barnum and Bailey’s circus in the United States, but its career ended when a tragic accident took the life of its driver.