by Timothy Don

The current economic crisis is crushing artists, museums, and galleries everywhere. In the San Francisco Bay Area, where I live, an exorbitant rental market made maintaining a practice difficult before this crisis hit. It’s even harder now. With 3QD’s permission, I’m going to use this column to talk about the work of some of the artists and art professionals I have met in the Bay Area. I ask you to support artists wherever you find them and however you can.

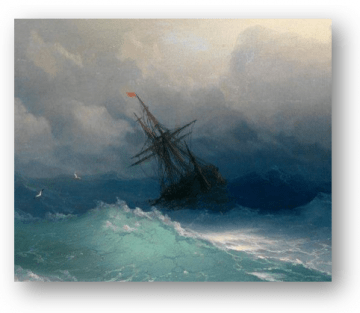

Roman Women XIII, by Sara VanDerBeek, 2013. Digital c-print, 66 x 47 3/4 in. From the series Roman Women.

A digitally manipulated and synthetically colored contemporary photograph of a sculptural object from classical-era Rome, this piece looks at first glance like a picture postcard, memento of a delightful afternoon spent at the Vatican museum. Look more closely, however: in subject matter and method, the work addresses and bridges in one stroke both the ancient world and our present moment. It projects the textures and patinas of the past onto the flat screens of the present, and it resituates that present as a way station on the journey through time of images and ideas, meanings and ideologies. It is both art and artifact.

We have become accustomed over the last several hundred years to an image of antiquity hewn from white marble: clean, harmonious, and transcendent; conceptually pure, flawlessly executed. In a word: Classical. Recent historical research, however, suggests that Roman statuary, along with the Greek originals that it copied, was polychromatic, embellished, and almost luridly vibrant. Sara VanDer Beek recalls this aspect of classical art by saturating her photograph with a shade of violet approaching Tyrian purple. She reminds us that classical doesn’t mean white. Classical was colorful.

Her aim, however, is not merely to introduce visual facticity to the historical record. This is a photograph of a copy of a lost original. It is the top layer in a stack of reproducible objects, evidence of the layering effect of and through which history is composed. This picture is then-and-now, uniquely contemporary in its utilization of present-day technologies of representation, archival in its reinscription of that technology within a geneology of visual representation dating back to the birth of western civilization. This piece accomplishes the same movement (from past to present and back again) with regard to its subject matter: the human female form. Read more »

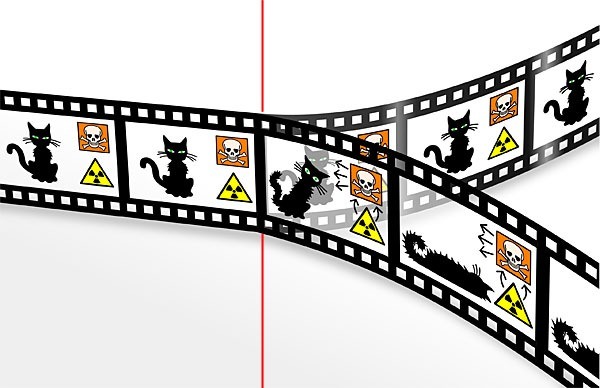

“I’ll just google it again”, said my daughter when I asked her to remember something. It was a very reasonable suggestion, but it led me down an interesting line of thought about the nature of knowing and its recent transformation. Much has been said and written about how the Internet has changed human knowledge, in both positive and negative ways. The positives are obvious. The magic of the Internet, the World-Wide Web, and utilities such as Google and Wikipedia, have put enormous knowledge at our disposal. Now any teenager with a smartphone has effortless access to far more information than the greatest minds of a century ago. Even more importantly, the Internet has opened up vast new possibilities of learning from others, and allowed people to share ideas in ways that were unimaginable until recently. Not surprisingly, all this has led to a great flowering of knowledge and creativity – though, unfortunately, not without an equally great multiplication of error and confusion.

“I’ll just google it again”, said my daughter when I asked her to remember something. It was a very reasonable suggestion, but it led me down an interesting line of thought about the nature of knowing and its recent transformation. Much has been said and written about how the Internet has changed human knowledge, in both positive and negative ways. The positives are obvious. The magic of the Internet, the World-Wide Web, and utilities such as Google and Wikipedia, have put enormous knowledge at our disposal. Now any teenager with a smartphone has effortless access to far more information than the greatest minds of a century ago. Even more importantly, the Internet has opened up vast new possibilities of learning from others, and allowed people to share ideas in ways that were unimaginable until recently. Not surprisingly, all this has led to a great flowering of knowledge and creativity – though, unfortunately, not without an equally great multiplication of error and confusion.

By 2025, protective living communities (PLCs) had started to form. The earliest PLCs, such as New Promise and New New Babylon, based themselves on rationalist doctrines: decisions informed by best available science, and either utilitarian ethics or Rawlsian principles of justice (principally, respect for individual autonomy and a concern to improve the lives of those most disadvantaged). Membership in these communities was exclusive and tightly guarded, and they had the advantage of the relatively higher levels of wealth controlled by their members.

By 2025, protective living communities (PLCs) had started to form. The earliest PLCs, such as New Promise and New New Babylon, based themselves on rationalist doctrines: decisions informed by best available science, and either utilitarian ethics or Rawlsian principles of justice (principally, respect for individual autonomy and a concern to improve the lives of those most disadvantaged). Membership in these communities was exclusive and tightly guarded, and they had the advantage of the relatively higher levels of wealth controlled by their members.

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose.

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose. Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.