I was hanging out on Twitter the other day, discussing my previous 3QD piece (about Progress Studies) with Hollis Robbins, Dean of Arts and Humanities at Cal State at Sonoma. We were breezing along at 240 characters per message unit when, Wham! right out of the blue the inspiration hit me: How about an interview?

Thus I have the pleasure of bringing another Johns Hopkins graduate into orbit around 3QD. Hollis graduated in ’83; Michael Liss, right about the corner, in ’77; and Abbas Raza, our editor, in ’85; I’m class of ’69. Both of us studied with and were influenced by the late Dick Macksey, a humanist polymath at Hopkins with a fabulous rare book collection. I know Michael took a course with Macksey and Abbas, alas, he missed out, but he met Hugh Kenner, who was his girlfriend’s advisor.

Robbins has also been Director of the Africana Studies program at Hopkins and chaired the Department of Humanities at the Peabody Institute. Peabody was an independent school when I took trumpet lessons from Harold Rehrig back in the early 1970s. It started dating Hopkins in 1978 and they got hitched in 1985.

And – you see – another connection. Robbins’ father played trumpet in the jazz band at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in the 1950s. A quarter of a century later I was on the faculty there and ventured into the jazz band, which was student run.

It’s fate I call it, destiny, kismet. [Social networks, fool!]

Robbins has published this and that all over the place, including her own poetry, and she’s worked with Henry Louis “Skip” Gates, Jr. to give us The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin (2006). Not only was Uncle Tom’s Cabin a best seller in its day (mid-19th century), but an enormous swath of popular culture rests on its foundations. If you haven’t yet done so, read it.

She’s here to talk about her most recent book, just out: Forms of Contention: Influence and the African American Sonnet Tradition. Read more »

Physics writing, let’s face it, is usually pretty boring. In a recent

Physics writing, let’s face it, is usually pretty boring. In a recent

I have a friend who is a self-described “cop magnet.” He’s been arrested six or seven times, just standing there.

I have a friend who is a self-described “cop magnet.” He’s been arrested six or seven times, just standing there.

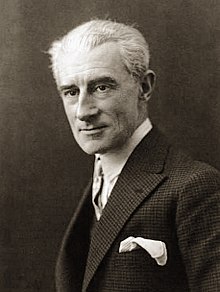

Lately I’ve been craving the music of French composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). As reality continues to be fraught, in the midst of a pandemic, social unrest, culture wars, and on and on, Ravel’s music offers an enticing escape. Described by his close friend, concert pianist Ricardo Viñes, as “inclined by temperament toward the poetic and fanciful,” Ravel created music that continues to captivate with its otherworldly beauty. Another reason for his appeal now, when the public health crisis has disrupted all of our quotidian rhythms, is that rhythm is the sine qua non of Ravel’s art. All you have to do is listen to

Lately I’ve been craving the music of French composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). As reality continues to be fraught, in the midst of a pandemic, social unrest, culture wars, and on and on, Ravel’s music offers an enticing escape. Described by his close friend, concert pianist Ricardo Viñes, as “inclined by temperament toward the poetic and fanciful,” Ravel created music that continues to captivate with its otherworldly beauty. Another reason for his appeal now, when the public health crisis has disrupted all of our quotidian rhythms, is that rhythm is the sine qua non of Ravel’s art. All you have to do is listen to

Being Korean is a behavioral science all its own. There are formalities at all levels of society and potential affronts lurking in every social engagement. Ageism is set in stone, and in honorifics that define older or younger persons, friends, siblings and relatives, as well as differing levels of social standing. Personal humiliations are many and varied, some of them universally recognizable, some of them exclusive to Korea’s tight-knit family structures or evident hierarchies. It goes beyond how to address someone: How to drink soju, how to pour it for a superior, how to bow, when to bow, who to bow to, when to get down on your knees—the list goes on.

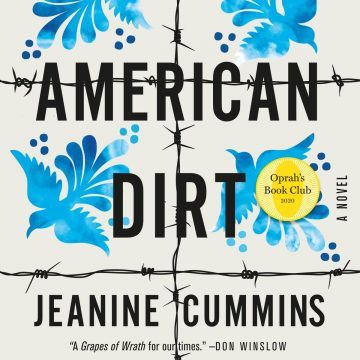

Being Korean is a behavioral science all its own. There are formalities at all levels of society and potential affronts lurking in every social engagement. Ageism is set in stone, and in honorifics that define older or younger persons, friends, siblings and relatives, as well as differing levels of social standing. Personal humiliations are many and varied, some of them universally recognizable, some of them exclusive to Korea’s tight-knit family structures or evident hierarchies. It goes beyond how to address someone: How to drink soju, how to pour it for a superior, how to bow, when to bow, who to bow to, when to get down on your knees—the list goes on. Jeanine Cummins’ American Dirt is a string pulled so tightly it is on the verge, always, of snapping. It is like this from the first sentence, when our protagonist Lydia Quixano Alvarez’s 8-year-old son, Luca, finds himself in a rain of bullets while he uses the bathroom. By the second page, sixteen members of Lydia and Luca’s family are dead, murdered by the reigning drug cartel of Acapulco, Mexico.

Jeanine Cummins’ American Dirt is a string pulled so tightly it is on the verge, always, of snapping. It is like this from the first sentence, when our protagonist Lydia Quixano Alvarez’s 8-year-old son, Luca, finds himself in a rain of bullets while he uses the bathroom. By the second page, sixteen members of Lydia and Luca’s family are dead, murdered by the reigning drug cartel of Acapulco, Mexico. The language of light is compelling. The suggestions of light at daybreak are vastly different from twilight or starlight, the light of a firefly is not the same as that of embers or cat eyes, and light through a sapphire ring or a stained glass window is not the same as light through the red siren of an emergency vehicle or through rice-paper lanterns at a festival. It matters to writers if the image they are crafting of light is flickering or glowing, glaring or fading, shimmering or dappled. A writer friend once commented on light as a recurring motif in my poetry, and told me that I’d enjoy her son’s work as a light-artist for theater. The thought struck me that light in a theater has a great hypnotic, silent power; it commands and manipulates not only where the audience’s attention must be held or shifted, how much of the scene is to be revealed or concealed, but also negotiates the many emotive subtleties and changes of mood. The same goes for cinema, photography, and other visual arts. Light almost always accompanies meaning.

The language of light is compelling. The suggestions of light at daybreak are vastly different from twilight or starlight, the light of a firefly is not the same as that of embers or cat eyes, and light through a sapphire ring or a stained glass window is not the same as light through the red siren of an emergency vehicle or through rice-paper lanterns at a festival. It matters to writers if the image they are crafting of light is flickering or glowing, glaring or fading, shimmering or dappled. A writer friend once commented on light as a recurring motif in my poetry, and told me that I’d enjoy her son’s work as a light-artist for theater. The thought struck me that light in a theater has a great hypnotic, silent power; it commands and manipulates not only where the audience’s attention must be held or shifted, how much of the scene is to be revealed or concealed, but also negotiates the many emotive subtleties and changes of mood. The same goes for cinema, photography, and other visual arts. Light almost always accompanies meaning.

“I’ll just google it again”, said my daughter when I asked her to remember something. It was a very reasonable suggestion, but it led me down an interesting line of thought about the nature of knowing and its recent transformation. Much has been said and written about how the Internet has changed human knowledge, in both positive and negative ways. The positives are obvious. The magic of the Internet, the World-Wide Web, and utilities such as Google and Wikipedia, have put enormous knowledge at our disposal. Now any teenager with a smartphone has effortless access to far more information than the greatest minds of a century ago. Even more importantly, the Internet has opened up vast new possibilities of learning from others, and allowed people to share ideas in ways that were unimaginable until recently. Not surprisingly, all this has led to a great flowering of knowledge and creativity – though, unfortunately, not without an equally great multiplication of error and confusion.

“I’ll just google it again”, said my daughter when I asked her to remember something. It was a very reasonable suggestion, but it led me down an interesting line of thought about the nature of knowing and its recent transformation. Much has been said and written about how the Internet has changed human knowledge, in both positive and negative ways. The positives are obvious. The magic of the Internet, the World-Wide Web, and utilities such as Google and Wikipedia, have put enormous knowledge at our disposal. Now any teenager with a smartphone has effortless access to far more information than the greatest minds of a century ago. Even more importantly, the Internet has opened up vast new possibilities of learning from others, and allowed people to share ideas in ways that were unimaginable until recently. Not surprisingly, all this has led to a great flowering of knowledge and creativity – though, unfortunately, not without an equally great multiplication of error and confusion.