by Eric Miller

1.

On occasion, a long epoch of concord with a favouring breeze may seem to grace us: inspiration in the sense that birds must relish it. What a divine—almost avian—thing it was for us, the hotel kitchen staff, to pack cheesecake, kiwifruit and champagne into our rucksacks, to tighten the straps that secured these dainties on our shoulders, and to climb right from the back exit with its tubs of lard to the stark summit of a Rocky Mountain in Alberta.

We felt we flew or, to speak more precisely, scudded upward. I wore shorts and a clean undershirt and sneakers with no socks, my colleagues wore nothing more substantial, and we scaled the steep flank of the darkling peak as though, like magpies, we half hopped, half sailed, never shaking off an appearance of indolence in spite of the winged celerity of our ascent. We might have kicked altitude away beneath our flexing feet, bubbling giddily like divers whom ebullience, in shimmering snorts of submerged laughter, expedites to the water’s surface.

After night fell, a thunderstorm broke out well below us in the valley. We were dry. We watched the lightning flash and fret; it resembled the dome and tassels of a jellyfish aglow in a cove. The spectacle of electrical unrest promoted our repose. When one couple began to thrash in a single sleeping bag, they rejoiced us, intimately clustered on that narrow summit, with the audible excess of their droll yet solemn ecstasy. The sounds they made as they scaled in duet the scarp of their pleasure amounted to musical improvisation, disclosure rather than presumption of form: a gasping flag or panting plume to mark—to augment—the height of the mountain and our happiness. Making instruments of each other, musicians of each other, they performed for and they warmed us. Sonorous fire! Read more »

Actress Cameron Diaz and her business partner, the entrepreneur Katherine Power, have been all over various media promoting

Actress Cameron Diaz and her business partner, the entrepreneur Katherine Power, have been all over various media promoting

On November 11, 2019, I wrote a

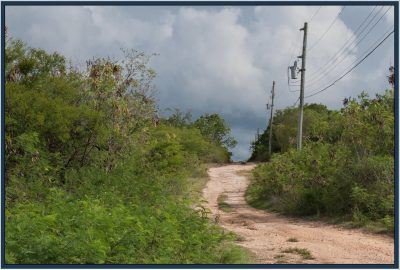

On November 11, 2019, I wrote a  In 1997, I was living on Ambae, a tiny, tropical island in the western South Pacific. Rugged, jungle-draped, steamy, volcanic Ambae belongs to Vanuatu, an archipelago nation stretching some 540 miles roughly between Fiji and Papua New Guinea. There, under corrugated tin roofs, in the cinderblock classrooms of a small, residential school, I taught science to middle- and high-schoolers as a Peace Corps volunteer.

In 1997, I was living on Ambae, a tiny, tropical island in the western South Pacific. Rugged, jungle-draped, steamy, volcanic Ambae belongs to Vanuatu, an archipelago nation stretching some 540 miles roughly between Fiji and Papua New Guinea. There, under corrugated tin roofs, in the cinderblock classrooms of a small, residential school, I taught science to middle- and high-schoolers as a Peace Corps volunteer.

In the Age of Trump, the banality of evil can perhaps best be defined as unfettered self-interest. Banal because everyone has self-interest, and because American culture expects and even celebrates its most gratuitous pursuits and expressions. Evil because, when unchecked, self-interest leads not only to intolerable disparities in wealth and power, but eventually the erosion of democratic norms.

In the Age of Trump, the banality of evil can perhaps best be defined as unfettered self-interest. Banal because everyone has self-interest, and because American culture expects and even celebrates its most gratuitous pursuits and expressions. Evil because, when unchecked, self-interest leads not only to intolerable disparities in wealth and power, but eventually the erosion of democratic norms. I may rise in the morning and notice that a long overdue spring rainfall has revived the flagging vegetation in my kitchen garden. I may give thanks to an unseen, benevolent power for this respite from a protracted and wasting drought. And I may record in my journal: “The heavens cannot horde the juice eternal / The sun draws from the thirsty acres vernal.” In such exercises, I will not have practised rigorous inquiry into the causes of things; I will not have subscribed to any particular view of the metaphysical; and I will certainly not have produced literature. But I will have replicated the conditions for the birth of science, as sketched by Geoffrey Lloyd in his account of the pre-Socratic philosophers, the first thinkers (at least in the Western world) to consider natural phenomena as distinct from the supernatural, however devoutly they may have believed in the latter; and who frequently set down their observations, theories and conclusions in formal language. For my observation of a natural phenomenon (rain and its effect on plant life), while not methodical, would bespeak a willingness to collect and consider empirical data unconstrained by superstitious tradition, and would not necessarily be contradicted by my ensuing prayer of gratitude to a supernatural force; and the verse elaboration of my findings into a speculative theory would not consign them to the realm of poetry (or even doggerel), but would merely represent a formal convention, whose forebears include Hesiod, Xenophanes, Lucretius and Vergil.

I may rise in the morning and notice that a long overdue spring rainfall has revived the flagging vegetation in my kitchen garden. I may give thanks to an unseen, benevolent power for this respite from a protracted and wasting drought. And I may record in my journal: “The heavens cannot horde the juice eternal / The sun draws from the thirsty acres vernal.” In such exercises, I will not have practised rigorous inquiry into the causes of things; I will not have subscribed to any particular view of the metaphysical; and I will certainly not have produced literature. But I will have replicated the conditions for the birth of science, as sketched by Geoffrey Lloyd in his account of the pre-Socratic philosophers, the first thinkers (at least in the Western world) to consider natural phenomena as distinct from the supernatural, however devoutly they may have believed in the latter; and who frequently set down their observations, theories and conclusions in formal language. For my observation of a natural phenomenon (rain and its effect on plant life), while not methodical, would bespeak a willingness to collect and consider empirical data unconstrained by superstitious tradition, and would not necessarily be contradicted by my ensuing prayer of gratitude to a supernatural force; and the verse elaboration of my findings into a speculative theory would not consign them to the realm of poetry (or even doggerel), but would merely represent a formal convention, whose forebears include Hesiod, Xenophanes, Lucretius and Vergil. Rutger Bregman’s Humankind: A Hopeful History is a clearly written argument if ever there was one. Bregman believes humans are a kind species and that we should arrange society accordingly. The reason why this thesis needs intellectual support at all is not that it is particularly profound or complicated, but that there are so many misunderstandings to be cleared away, so many apparent objections that need to be overcome.

Rutger Bregman’s Humankind: A Hopeful History is a clearly written argument if ever there was one. Bregman believes humans are a kind species and that we should arrange society accordingly. The reason why this thesis needs intellectual support at all is not that it is particularly profound or complicated, but that there are so many misunderstandings to be cleared away, so many apparent objections that need to be overcome.

Anguilla is a sandbar ten miles long. It’s three miles wide if you’re being generous, but generous isn’t a word that pairs well with the endowments of a small, arid skerry of sand pocked with salt ponds.

Anguilla is a sandbar ten miles long. It’s three miles wide if you’re being generous, but generous isn’t a word that pairs well with the endowments of a small, arid skerry of sand pocked with salt ponds.