by Claire Chambers

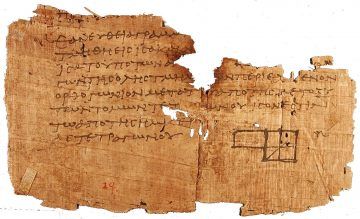

Ghazal poetry is an intimate and relatively short lyric form of verse from the Middle East and South Asia. The form thrives in such languages as Arabic, Persian, Urdu, and now English. Like the Western ode, these poems are often addressed to a love object. Influenced by ecstatic Sufi Islam, the ghazal’s subject matter concerns desire for another person and, figuratively, love for the Divine.

Indeed, a mixture of sacred, profane, romantic, and melancholic elements are frequently stitched into the ghazal’s poetic fabric. Many ghazals revolve around the theme of lovers’ separation. This topic also functions as an image for the Muslim worshipper’s longing for Allah. In doing so, the ghazal draws comparisons with seventeenth-century metaphysical poetry. Like ghazalists, John Donne would ostensibly write about love for a woman but also shadow forth devotion to God.

Sound, rhyme, repetition, and rhythm come to the forefront in this form. This makes it unsurprising that many ghazals have been turned into songs. For instance, during the course of his illustrious poetic career, Mohammad (‘Allama’) Iqbal (1877–1938) wrote dozens of ghazals. Some of these poems have been set to music. They were sung by popular South Asian musicians including the late Mehdi Hassan and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, as well as contemporary singers Lata Mangeshkar and Sanam Marvi. I also think of the famous playback singers Noor Jehan’s and Nayyara Noor’s renditions of the poetry of Faiz Ahmed Faiz (1911–1984). This crossover often surprises Westerners: it’s as though Carol Ann Duffy’s poems were being sung by Rihanna! Read more »

Many social commentators in the claustrophobic gloom of their self-isolation have shown a tendency to write in somewhat feverish apocalyptic terms about the near future. Some of them expect the pre-existing dysfunctionalities of social and political institutions to accelerate in the post-pandemic world and anticipate our going down a vicious spiral. Others are a bit more hopeful in envisaging a world where the corona crisis will make people wake up to the deep fault lines it has revealed and try to mend things toward a better world. Some others take an intermediate position of what is called upbeat cynicism: hold out for things to be better but guess that will not happen (somewhat akin to Antonio Gramsci’s “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will”).

Many social commentators in the claustrophobic gloom of their self-isolation have shown a tendency to write in somewhat feverish apocalyptic terms about the near future. Some of them expect the pre-existing dysfunctionalities of social and political institutions to accelerate in the post-pandemic world and anticipate our going down a vicious spiral. Others are a bit more hopeful in envisaging a world where the corona crisis will make people wake up to the deep fault lines it has revealed and try to mend things toward a better world. Some others take an intermediate position of what is called upbeat cynicism: hold out for things to be better but guess that will not happen (somewhat akin to Antonio Gramsci’s “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will”). Throughout history there have been prophets of doom and prophets of hope. The prophets of doom are often more visible; the prophets of hope are often more important. The Danish economist Bjorn Lomborg is a prophet of hope. For more than ten years he has been questioning the consensus associated with global warming. Lomborg is not a global warming denier but is a skeptic and realist. He does not question the basic facts of global warming or the contribution of human activity to it. He does not deny that global warming will have some bad effects. But he does question the exaggerated claims, he does question whether it’s the only problem worth addressing, he certainly questions the intense politicization of the issue that makes rational discussion hard and he is critical of the measures being proposed by world governments at the expense of better and cheaper ones. Lomborg is a skeptic who respects the other side’s arguments and tries to refute them with data.

Throughout history there have been prophets of doom and prophets of hope. The prophets of doom are often more visible; the prophets of hope are often more important. The Danish economist Bjorn Lomborg is a prophet of hope. For more than ten years he has been questioning the consensus associated with global warming. Lomborg is not a global warming denier but is a skeptic and realist. He does not question the basic facts of global warming or the contribution of human activity to it. He does not deny that global warming will have some bad effects. But he does question the exaggerated claims, he does question whether it’s the only problem worth addressing, he certainly questions the intense politicization of the issue that makes rational discussion hard and he is critical of the measures being proposed by world governments at the expense of better and cheaper ones. Lomborg is a skeptic who respects the other side’s arguments and tries to refute them with data.

In one sense, the stories of the collection Almost No Memory, originally published in 1997 and reprinted in The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis in 2009, can be read as a psychological portrait of a middle-aged woman coming to terms with all the usual things life has to offer after a certain age: the convolutions of domestic discord, shrinking horizons, the sobering insight that very little can change us anymore. The voices are both many and one, converging in a polyphony of percipient anxiety and resignation: we hear “wife one,” an “often raging though now quiet woman” eating dinner alone after talking on the phone to “wife two”; a professor who fantasizes about marrying a cowboy, although she is “so used to the companionship of [her] husband by now that if I were to marry a cowboy I would want to take him with me”; and a woman who “fell in love with a man who had been dead a number of years.” There is also a woman who “comes running out of the house with her face white and her overcoat flapping wildly,” crying “emergency, emergency”; a woman who wishes she had a second chance to learn from her mistakes; and one who has “no choice but to continue to proceed as if I know altogether what I am, though I may also try to guess, from time to time, just what it is that others know that I do not know.” The list continues, from a woman wondering why she can become so vicious with her children to another whose mind wanders to sex at the sight of “anything pounding, anything stroking; anything bolt upright, anything horizontal and gaping” and one who is filled with “ill will toward one I think I should love, ill will toward myself, and discouragement over the work I think I should be doing.”

In one sense, the stories of the collection Almost No Memory, originally published in 1997 and reprinted in The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis in 2009, can be read as a psychological portrait of a middle-aged woman coming to terms with all the usual things life has to offer after a certain age: the convolutions of domestic discord, shrinking horizons, the sobering insight that very little can change us anymore. The voices are both many and one, converging in a polyphony of percipient anxiety and resignation: we hear “wife one,” an “often raging though now quiet woman” eating dinner alone after talking on the phone to “wife two”; a professor who fantasizes about marrying a cowboy, although she is “so used to the companionship of [her] husband by now that if I were to marry a cowboy I would want to take him with me”; and a woman who “fell in love with a man who had been dead a number of years.” There is also a woman who “comes running out of the house with her face white and her overcoat flapping wildly,” crying “emergency, emergency”; a woman who wishes she had a second chance to learn from her mistakes; and one who has “no choice but to continue to proceed as if I know altogether what I am, though I may also try to guess, from time to time, just what it is that others know that I do not know.” The list continues, from a woman wondering why she can become so vicious with her children to another whose mind wanders to sex at the sight of “anything pounding, anything stroking; anything bolt upright, anything horizontal and gaping” and one who is filled with “ill will toward one I think I should love, ill will toward myself, and discouragement over the work I think I should be doing.” Undoubtedly many insights and lessons can be drawn and will be drawn for a long time to come from the current worldwide covid19 epidemic; insights, for example, about the responsibility of politicians in the managing of health crises, about the importance of human cooperation both locally and internationally, about the vulnerability of the global economy to disturbances in the regular flow of people and commodities, about the crucial yet contentious role of the various media in the dissemination of information, etc. But here I am interested in focusing briefly on related issues regarding the problematic relationship of science and the general public. Specifically, I want to offer some reflections on why I think science in trying times can be hard to live with.

Undoubtedly many insights and lessons can be drawn and will be drawn for a long time to come from the current worldwide covid19 epidemic; insights, for example, about the responsibility of politicians in the managing of health crises, about the importance of human cooperation both locally and internationally, about the vulnerability of the global economy to disturbances in the regular flow of people and commodities, about the crucial yet contentious role of the various media in the dissemination of information, etc. But here I am interested in focusing briefly on related issues regarding the problematic relationship of science and the general public. Specifically, I want to offer some reflections on why I think science in trying times can be hard to live with.

Our classes in the British university where I was teaching Pre-sessional students (mainly Chinese) were cancelled for a Special Event. Instead of their normal lessons on academic English, our students were shepherded off to witness a series of presentations on ‘learning.’ Learning, they were told, was ‘Collaborative,’ ‘Creative,’ and ‘Self-directed,’ and depended upon ‘Taking Responsibility for one’s own learning,’ ‘Thinking Critically,’ ‘Problem-solving’ and ‘Taking the Initiative.’

Our classes in the British university where I was teaching Pre-sessional students (mainly Chinese) were cancelled for a Special Event. Instead of their normal lessons on academic English, our students were shepherded off to witness a series of presentations on ‘learning.’ Learning, they were told, was ‘Collaborative,’ ‘Creative,’ and ‘Self-directed,’ and depended upon ‘Taking Responsibility for one’s own learning,’ ‘Thinking Critically,’ ‘Problem-solving’ and ‘Taking the Initiative.’ I began taking piano lessons when I was 8 years old, along with Lynn, my older and Mark, one of my brothers. Every Wednesday we’d walk together from school to a small storefront on Milwaukee Avenue about a half mile away. The store windows were covered in drapes, with a little sign indicating the teacher’s name and PIANO LESSONS. My sister gave her the $3 for three lessons, and we entered the small studio, which had a grand piano and a sofa, bookshelves, and a heavy, dusty drape separating the studio from the living quarters. We’d each wait patiently, doing our homework on the sofa while the other one had his or her lesson.

I began taking piano lessons when I was 8 years old, along with Lynn, my older and Mark, one of my brothers. Every Wednesday we’d walk together from school to a small storefront on Milwaukee Avenue about a half mile away. The store windows were covered in drapes, with a little sign indicating the teacher’s name and PIANO LESSONS. My sister gave her the $3 for three lessons, and we entered the small studio, which had a grand piano and a sofa, bookshelves, and a heavy, dusty drape separating the studio from the living quarters. We’d each wait patiently, doing our homework on the sofa while the other one had his or her lesson. We enjoyed learning the piano, but didn’t enjoy Mrs. K. She was creepy. We thought she might have been a Roma fortune teller or a magician, as she wore strange jewelry and shawls, and had Persian carpets and draperies around her studio. To us kids she looked about 90 years old (probably more like 40). She was actually a rather unsuccessful concert pianist, and memorabilia was scattered around the studio such as notices of performances and autographed pictures of famous conductors. She didn’t talk about it much her past life at all, as she was reduced to teaching piano lessons to the blue-collar neighborhood kids like ourselves. We persisted with lessons because we always did as we were told. We went home and put in our half-hour of practice on the second-hand but well-tuned piano that dad bought for us, and little by little we began to learn how to play.

We enjoyed learning the piano, but didn’t enjoy Mrs. K. She was creepy. We thought she might have been a Roma fortune teller or a magician, as she wore strange jewelry and shawls, and had Persian carpets and draperies around her studio. To us kids she looked about 90 years old (probably more like 40). She was actually a rather unsuccessful concert pianist, and memorabilia was scattered around the studio such as notices of performances and autographed pictures of famous conductors. She didn’t talk about it much her past life at all, as she was reduced to teaching piano lessons to the blue-collar neighborhood kids like ourselves. We persisted with lessons because we always did as we were told. We went home and put in our half-hour of practice on the second-hand but well-tuned piano that dad bought for us, and little by little we began to learn how to play.  America is a truck rolling down a hill towards a cliff. The downhill slope is the erosion of democratic norms; the cliff is the point where anti-democratic forces become powerful enough to crush democratic opposition by authoritarian means. The re-election of Donald Trump would very likely see the country sail over that cliff.

America is a truck rolling down a hill towards a cliff. The downhill slope is the erosion of democratic norms; the cliff is the point where anti-democratic forces become powerful enough to crush democratic opposition by authoritarian means. The re-election of Donald Trump would very likely see the country sail over that cliff.