by Rafiq Kathwari

“Battle of Algiers”, a classic 1966 film directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, seized my imagination and of my classmates as well when it was shown three years later at the Palladium in Srinagar. A teenager wearing bell-bottoms, dancing the twist, I was a Senior at Sri Pratap College, named after Maharajah Pratap Singh, a Hindu Dogra ruler of Muslim majority Kashmir.

“Battle of Algiers”, a classic 1966 film directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, seized my imagination and of my classmates as well when it was shown three years later at the Palladium in Srinagar. A teenager wearing bell-bottoms, dancing the twist, I was a Senior at Sri Pratap College, named after Maharajah Pratap Singh, a Hindu Dogra ruler of Muslim majority Kashmir.

Would I fight to make Kashmir free? A classmate asked few days later when we met at the Premier Coffee House on Residency Road, the film fresh on our minds. Of course, I said, my heart leaping. He unfolded a poster:

‘Bear Arms Against a Sea of Troubles’

“This is our manifesto,” he said. I read on

‘Aims & Objectives: Demolish Bunkers * Occupy the Radio Station * Disrupt the Telephone Exchange *Ambush Convoys * Create a Pyramid of Freedom Fighters’

I had questions: how many boys in the group, who was our leader, where would we get arms, when will we act? “Don’t ask,” my classmate said, raising his arms. “Man proposes. Allah disposes.” I read on:

‘Our cause is freedom. India promised us a plebiscite to determine our own future, but broke her promise. She has jailed our leader, the “Lion of Kashmir,” because he roared for freedom. To the extent India denies us our birthright to that extent India subverts its own democracy.’

This was fantastic stuff. I was impressionable. If the Algerians could do it so could Kashmiris.

I signed the poster with a flourish. The coffee tasted sweeter than usual.

A week later, my teenage flirtation landed me in Central Jail where I met seven classmates who had also signed the manifesto. We later learnt that one poster had been brought to the office of the college principal, who had his own sword to sharpen, and he rang the police. Read more »

I remember as a child watching the made-for-tv movie

I remember as a child watching the made-for-tv movie  Whether or not a certain line of work is shameful or honorable is culturally relative, varying greatly between places and over time. Farmers, soldiers, actors, dentists, prostitutes, pirates and priests have all been respected or despised in some society or other. There are numerous reasons why certain kinds of work have been looked down on. Subjecting oneself to the will of another; doing tasks that are considered inappropriate given one’s sex, race, age, or class; doing work that is unpopular (tax collector); or deemed immoral (prostitution), or viewed as worthless (what David Graeber labelled “bullshit jobs”), or which are just very poorly paid–all these could be reasons why a kind of work is despised, even by those who do it. One of the oldest prejudices though, at least among the upper classes in many societies, is against manual labour.

Whether or not a certain line of work is shameful or honorable is culturally relative, varying greatly between places and over time. Farmers, soldiers, actors, dentists, prostitutes, pirates and priests have all been respected or despised in some society or other. There are numerous reasons why certain kinds of work have been looked down on. Subjecting oneself to the will of another; doing tasks that are considered inappropriate given one’s sex, race, age, or class; doing work that is unpopular (tax collector); or deemed immoral (prostitution), or viewed as worthless (what David Graeber labelled “bullshit jobs”), or which are just very poorly paid–all these could be reasons why a kind of work is despised, even by those who do it. One of the oldest prejudices though, at least among the upper classes in many societies, is against manual labour.

A life in which the pleasures of food and drink are not important is missing a crucial dimension of a good life. Food and drink are a constant presence in our lives. They can be a constant source of pleasure if we nurture our connection to them and don’t take them for granted.

A life in which the pleasures of food and drink are not important is missing a crucial dimension of a good life. Food and drink are a constant presence in our lives. They can be a constant source of pleasure if we nurture our connection to them and don’t take them for granted. At the beginning of our story—paraphrased from an origin story remembered by a

At the beginning of our story—paraphrased from an origin story remembered by a  There is a minor American myth about shame and regret. It goes like this.

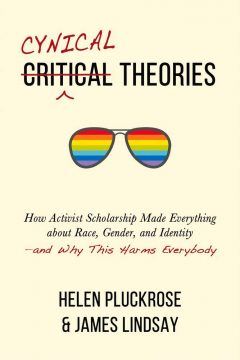

There is a minor American myth about shame and regret. It goes like this. The most charitable, forward-looking take on the science wars of the 90s is Stephen Jay Gould’s, in The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister’s Pox (2003), a delightful book about dichotomies between the sciences and humanities. His diagnosis is primarily that scientists have taken too literally or too seriously some fashionable nonsense, and overreacted; and if everybody can just calm down already, things will be alright and both sides could “break bread together” (108). Gould saw the science wars themselves as a marginal and slightly comical skirmish, almost a mere misunderstanding. “Some of my colleagues”, he said,

The most charitable, forward-looking take on the science wars of the 90s is Stephen Jay Gould’s, in The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister’s Pox (2003), a delightful book about dichotomies between the sciences and humanities. His diagnosis is primarily that scientists have taken too literally or too seriously some fashionable nonsense, and overreacted; and if everybody can just calm down already, things will be alright and both sides could “break bread together” (108). Gould saw the science wars themselves as a marginal and slightly comical skirmish, almost a mere misunderstanding. “Some of my colleagues”, he said, Sughra Raza. Light As a Feather. Boston, Sept 2020.

Sughra Raza. Light As a Feather. Boston, Sept 2020.

By the beginning of the 20th century, it had become clear to an influential minority of philosophers that something was badly amiss with modern philosophy. (There had been gripes of innumerable sorts since the beginning of modernity in the 17th century; but our subject today is the present.) “Modern” here means something like “Lockean and/or Cartesian,” where this means … well, it’s not immediately clear what exactly this means, nor what exactly is wrong with it, and therein lies the tale of a good deal of 20th-century philosophy. As with every broken thing, we have two choices: fix it, or throw it out and get a new one; and many philosophers have advertised their projects as doing one or the other. However, as we might expect, unclarity about the old results in corresponding unclarity about the supposedly better new. What’s the actual difference, philosophically speaking, between rehabilitation and replacement?

By the beginning of the 20th century, it had become clear to an influential minority of philosophers that something was badly amiss with modern philosophy. (There had been gripes of innumerable sorts since the beginning of modernity in the 17th century; but our subject today is the present.) “Modern” here means something like “Lockean and/or Cartesian,” where this means … well, it’s not immediately clear what exactly this means, nor what exactly is wrong with it, and therein lies the tale of a good deal of 20th-century philosophy. As with every broken thing, we have two choices: fix it, or throw it out and get a new one; and many philosophers have advertised their projects as doing one or the other. However, as we might expect, unclarity about the old results in corresponding unclarity about the supposedly better new. What’s the actual difference, philosophically speaking, between rehabilitation and replacement? Over the course of two days in early September, the Trump administration quietly formalized its commitment to the ideology of white supremacy within the context of schooling and public education. In two separate but parallel moves, both of which would have made Senator Joe McCarthy proud, Trump announced that the Department of Education (DOE) would investigate public schools to determine if they were using the Pulitzer-Prize winning curriculum, The

Over the course of two days in early September, the Trump administration quietly formalized its commitment to the ideology of white supremacy within the context of schooling and public education. In two separate but parallel moves, both of which would have made Senator Joe McCarthy proud, Trump announced that the Department of Education (DOE) would investigate public schools to determine if they were using the Pulitzer-Prize winning curriculum, The