by Fabio Tollon

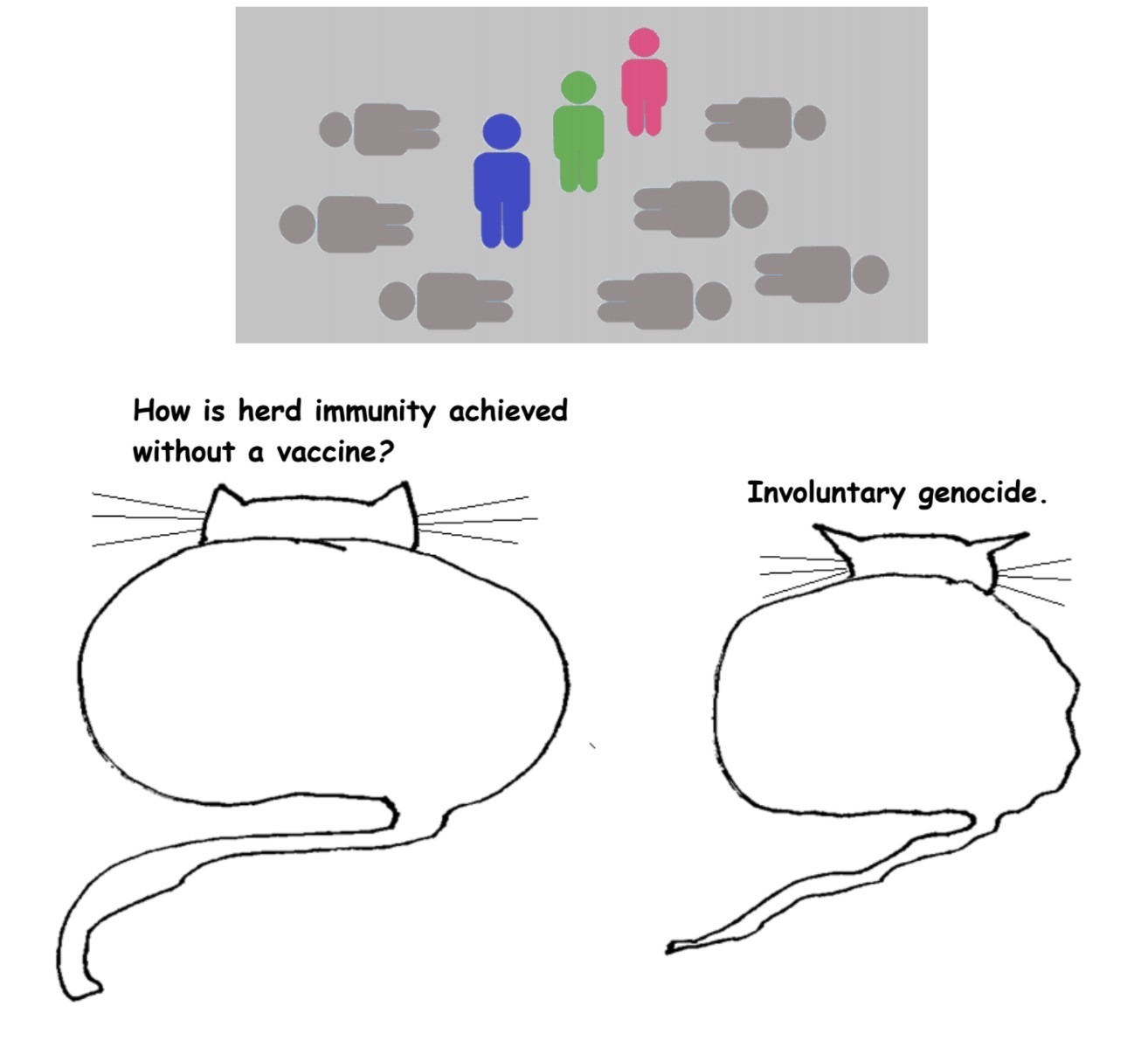

COVID-19 has forced populations into lockdown, seen the restriction of rights, and caused widespread economic, social, and psychological harm. With only 11 countries having no confirmed cases of COVID-19 (as of this writing), we are globally beyond strategies that aim solely at containment. Most resources are now being directed at mitigation strategies. That is, strategies that aim to curtail how quickly the virus spreads. These strategies (such as physical and social distancing, increased hand-washing, mask-wearing, and proper respiratory etiquette) have been effective in delaying infection rates, and therefore reducing strain on healthcare workers and facilities. There has also been a wave of techno-solutionism (not unusual in times of crisis), which often comes with the unjustified belief that technological solutions provide the best (and sometimes only) ways to deal with the crisis in question.

Such perspectives, in the words of Michael Klenk, ask “what technology”, instead of asking “why technology”, and therefore run the risk of creating more problems than they solve. Klenk argues that such a focus is too narrow: it starts with the presumption that there should be technological solutions to our problems, and then stamps some ethics on afterwards to try and constrain problematic developments that may occur with the technology. This gets things exactly backwards. What we should instead be doing is asking whether we need a given technology, and then proceed from there. It is with this critical perspective in mind that I will investigate a new technological kid on the block: digital contact tracing. Basically, its implementation involves installing a smartphone app that, via Bluetooth, registers and stores the individual’s contacts. Should a user become infected, they can update their app with this information, which will then automatically ping all of their registered contacts. While much attention has been focused on privacy and trust concerns, this will not be my focus (see here for a good example of an analysis that looks specifically at these factors, drawn up by the team at Ethical Intelligence). I will instead focus on the question of whether digital contact tracing is fair. Read more »

![Shakespeare & Company, Paris. [Wikipedia]](https://3quarksdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/SandC.jpg)

Racial disparities are present in all aspects of life. In the U.S.

Racial disparities are present in all aspects of life. In the U.S.  Some people whose political views are liberal and progressive say they will not vote in the 2020 US election. They detest Donald Trump and his Republican enablers like senate leader Mitch McConnell; they oppose Trump’s policies on most issues–the environment, immigration, health care, voting rights, police brutality, gun control, etc.; but they still say they won’t vote. Why not?

Some people whose political views are liberal and progressive say they will not vote in the 2020 US election. They detest Donald Trump and his Republican enablers like senate leader Mitch McConnell; they oppose Trump’s policies on most issues–the environment, immigration, health care, voting rights, police brutality, gun control, etc.; but they still say they won’t vote. Why not?

Last month’s most popular movie on Netflix is a horror show in the guise of a documentary. In 2020, reality has turned scarier than fiction, and The Social Dilemma expends more dread per minute than any episode of Black Mirror. It’s a timely, manipulative film, built for one purpose: to scare the f*ck out of everyday Americans.

Last month’s most popular movie on Netflix is a horror show in the guise of a documentary. In 2020, reality has turned scarier than fiction, and The Social Dilemma expends more dread per minute than any episode of Black Mirror. It’s a timely, manipulative film, built for one purpose: to scare the f*ck out of everyday Americans.

What did the wines that stimulated conversation in Plato’s Symposium taste like? Or the clam chowder in Moby Dick, or the “brown and yellow meats” served to Mr. Banks in To the Lighthouse? Or consider this repast from Joyce’s Ulysses:

What did the wines that stimulated conversation in Plato’s Symposium taste like? Or the clam chowder in Moby Dick, or the “brown and yellow meats” served to Mr. Banks in To the Lighthouse? Or consider this repast from Joyce’s Ulysses: Today in the United States is Indigenous Peoples’ Day, a time to bear witness and remember the savagery of Christopher Columbus and other European explorers when they first encountered indigenous peoples throughout the Americas. It’s also a day to recognize and celebrate the courage, knowledges, and cultures of indigenous peoples throughout the world. It coincides with Columbus Day, a national holiday that triggers a day of protests and celebratory parades, rekindles debates about removing statues of Christopher Columbus from parks, squares and circles throughout the United States, and provokes critical discussions about the kind of stories we should be teaching the Nation’s children about his earliest encounters with indigenous communities.

Today in the United States is Indigenous Peoples’ Day, a time to bear witness and remember the savagery of Christopher Columbus and other European explorers when they first encountered indigenous peoples throughout the Americas. It’s also a day to recognize and celebrate the courage, knowledges, and cultures of indigenous peoples throughout the world. It coincides with Columbus Day, a national holiday that triggers a day of protests and celebratory parades, rekindles debates about removing statues of Christopher Columbus from parks, squares and circles throughout the United States, and provokes critical discussions about the kind of stories we should be teaching the Nation’s children about his earliest encounters with indigenous communities. Although American history curriculum has always been a site of ideological struggle, historians, history teachers, and curriculum designers have done a good job over the past several decades to revise many historical inaccuracies, distortions, and lies that helped whitewash the historical record in the service of white, male, imperialistic, and neoliberal interests. But with Trump’s latest decree to create a “1776 Commission” charged to design a “pro-American” curriculum of American history coupled with his promise to defund schools that use the 1619 Project as well as other curricular platforms that bring attention to historical facts and truths that counter the “official” curriculum, the Nation’s collective historical memory is under siege with public schools at the center of the assault. Whether Trump and the GOP actually care about how American history is represented and taught in schools or whether they are just cynically using the issue to create a political wedge between people who may otherwise be allied to vote against Trump in November is irrelevant.

Although American history curriculum has always been a site of ideological struggle, historians, history teachers, and curriculum designers have done a good job over the past several decades to revise many historical inaccuracies, distortions, and lies that helped whitewash the historical record in the service of white, male, imperialistic, and neoliberal interests. But with Trump’s latest decree to create a “1776 Commission” charged to design a “pro-American” curriculum of American history coupled with his promise to defund schools that use the 1619 Project as well as other curricular platforms that bring attention to historical facts and truths that counter the “official” curriculum, the Nation’s collective historical memory is under siege with public schools at the center of the assault. Whether Trump and the GOP actually care about how American history is represented and taught in schools or whether they are just cynically using the issue to create a political wedge between people who may otherwise be allied to vote against Trump in November is irrelevant.