by Joshua Wilbur

The Palio di Siena is a gorgeous paradox, a horse race with practically no rules in a city enamored with ritual.

Representatives from the contrade, or neighborhoods, of Siena, Italy have competed in this unique spectacle since the 17th Century. Twice a summer, first in July and again in August, Tuscans and tourists gather in the stifling heat to watch a ten-horse, three-lap sprint lasting no longer than two minutes.

More than a race, Il Palio (“the prize”) is an expression of its people, an exercise in uninhibited passion, remnant barbarism, group solidarity, and shameless corruption. I’m fortunate to have extended family— cousins, cugini—who live in a village just outside of Siena. Last week, with my cousins as guides, I experienced the Palio for the first time.

On the day of the Palio, our group of family and friends (an even mix of Americans and Italians, plus a Canadian and a Cypriot) headed to the Piazza del Campo, where the race is held. Il Campo (“the field”) is one of the most impressive “squares” in Italy— in part because it’s a large, imperfect circle. The race rumbles along the piazza’s edge, past shops and restaurants obscured, for a few days, by wooden bleachers. A dense layer of clay, sand, and tuff is laid over the uneven brick sidewalk, protecting horses and riders from even worse potential injury.

The majority of the crowd congregate in the Campo’s center, a red-bricked circle-within-a-circle that sags below the perimeter. Looming overhead and to the east is the piazza’s medieval palace, the Palazzo Pubblico, with its Torre del Mangia stretching more than a hundred meters above. At dusk, thousands of starlings buffet the walls in coordinated dives: sundown is feeding time at the Tower of the Eater, which began construction in the same decade (the 1320s) that Dante finished his Divina Commedia.

Like many piazzas in Italy, the Campo exerts a powerful social gravity. Everything flows in its direction. If you’re lost or lonely or bored, simply go to the Campo— it’s easy to stumble into — and you’ll find friends. As an American, it’s impossible to visit the city’s center without feeling a pang of envy. It’s a space that structures and sustains town-life in ways untranslatable to the land of Interstates and Wal-Marts.

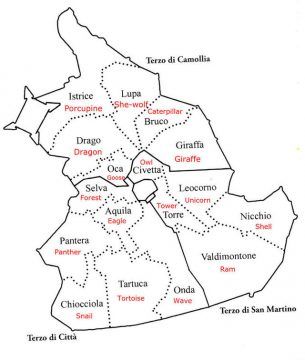

To reach the Campo, we walked through several of the town’s contrade, each ward identifiable by flags and statues aligning the sides of buildings. Most of the contrade are named after and symbolized by an animal, with a few exceptions. Membership is largely by birthright. There are seventeen wards in total, though only ten race in each Palio, as determined by the previous year’s non-participants (filling seven slots) and a drawing of lots (filling the remaining three slots). The contrade are: Aquila (Eagle), Bruco (Caterpillar), Chiocciola (Snail), Civetta (Little Owl), Drago (Dragon), Giraffa (Giraffe), Istrice (Crested Porcupine), Leocorno (Unicorn), Lupa (She-Wolf), Nicchio (Seashell), Oca (Goose), Onda (Wave), Pantera (Panther), Selva (Forest), Tartuca (Tortoise), Torre (Tower), and Valdimontone (Valley of the Ram).

Working our way through Aquila territory, we hugged stone walls in a single file, half the group shouting “Car!”, the other half shouting “Macchina!” as traffic flowed past. The district was awash in yellow, filled with drum beats and the contrada’s singing members, traditional bandiere (flags) tied around their necks. Locals can immediately identify out-of-towners by their store-purchased and pristine flags. Some in Siena welcome the interest and Euros of tourists; others are justifiably annoyed by the constant presence of itinerant outsiders.

I tried not to feel too guilty about my own status as a tourist. I wanted to take in the experience of a medieval city going through its favorite rhythms as a respectful observer. Even still, I joked with my brother and parents about forming our own contrada, one representing our home state of Texas. Our animal would be the armadillo, and our song would be “Deep in the Heart of Texas,” belted out at obnoxious volume. We’re often ironic about our heritage, proud but also self-aware of the excesses of Texas.

Arriving at the Campo, we funneled into a tiny bar with an outdoor balcony that would provide an excellent view of the proceedings. It was hot inside and packed tight with people. For two hours, we drank cold beer and minty aperitifs, snacked on assorted antipasti, and watched the Corteo Storico, a fantastic and courtly parade in which representatives from each contrade, dressed in stuffy medieval costumes and long wigs, bear regal banners and elaborate garlands. After marching through town with swords unsheathed and silver trumpets blaring— and after receiving blessings from a bishop and a city official, stewards of church and state— the contrade parties slowly circled the Campo’s dirt track and put on the pre-race entertainment: a flag-waving exhibition. With great coordination, two wavers from each contrada launched their flags high into the air in overlapping arcs, catching them in perfect synchrony. My cousin Federica told me that the flag-wavers practiced all year for the exhibition, and that the display is a judged competition in itself. “What does a contrada receive for winning?” I asked. “A decorated plate,” she said, smiling.

We met a few people at the bar, mostly foreigners. There was a friendly couple from the south of England, as excited about the Palio as we were. There was a family from Long Island, a mother and father touring Italy with their young son. Every few minutes, the mother complained about the intense sunshine roasting the cramped balcony. She asked me to stand “just like that” so she could sit in my shadow. I chatted with her son about baseball. His father commented on the incredible number of medical staff and military police present at the Campo’s exits. I saw more than one person stretchered away, suffering from heat exhaustion.

A man from Arizona, probably in his forties, made the most lasting impression. He was loud and sweaty, bumping around and making crude jokes. I offered him some sunscreen, and he sprayed it carelessly on himself and others. He downed several shots of cheap vodka at the bar, insisting that we join him, a risky thing to do considering the sweltering weather. All day, he wore the flag of Pantera around his neck, cluelessly.

In spite of him, our group enjoyed each other’s company as the anticipation mounted. My cousin Alberto, who speaks impeccable English, explained some of the more sordid aspects of the Palio. The jockeys are professional riders, hired by the contrade like mercenaries. They openly accept bribes and scheme in whispers, even (especially!) as the race is about to begin. Each contrada boasts a deep bank of money which influences the race in complicated ways. For example, a contrada with a poor starting position and a lesser horse — both assigned at random — might cut their losses and focus instead on sabotaging rival contrade. A well-compensated jockey might whip an opponent’s horse. Or allow another rider to pass. Or slow down on the final lap. The day after the Palio, I noticed a number of locals rewatching the race on YouTube, poring over the evidence in high definition. Our friend Mattia told me about an especially arrogant jockey, whom he despised but also respected, who said something like, “If the Palio were simply a matter of racing, I’d win every time.”

An explosion soon broke our discussion, a set detonation that startled many in the crowd and signalled that the race was about to start. The horses—all mixed-breeds and rode without saddles, some of them spooking left and right—entered the Campo and approached the starting line. One jockey, to the crowd’s collective gasp, fell off his horse as he made his entry. Since 1970, more than fifty horses have died as a result of the Palio, a troubling fact.

But now, silenzio, silence. Alberto had told us about the remarkable moment just before the start of the race, when the crowd becomes quiet as the jockeys vie for position. Twenty-thousand people looked on with bated breath as a single rider (la rincorsa), whose task it is to trigger the race by crossing into the starting zone, paced twenty feet behind the others, waiting for his moment. For several minutes, the jockeys struggled for advantageous angles, with la rincorsa refusing or unable to cross the line.

There was more than one false start. Some in the crowd punctuated the silence with angry shouts, whether at horses or riders or each other, I wasn’t certain. The man from Arizona, now very drunk, leaned over the balcony and shouted “C’mon, Burger King!” at the jockey of Pantera, whose colors are blue, red, and yellow, apparently resembling the company’s logo in the man’s small mind. Everyone groaned; his wife appeared mortified.

After a quarter of an hour, I was growing restless. My stomach tightened, and I shifted around uncomfortably. I wasn’t certain what to look for in the riders, and the Italians’ body language gave me the impression that it might take quite awhile longer. For a few minutes, I could sense that each of us was feeling the moment’s tension in our own way, isolated in our internal wondering, When will it start? When will it start?

But then the horses were sprinting, and the crowd let out a growing scream, like a volume knob suddenly twisted clockwise. In the first lap, two contrade quickly separated from the field, Giraffa and Chiocciola, with the snail out in front. I couldn’t process everything in real-time, but apparently several riders had difficulty getting off the starting line. After thirty seconds, it was essentially a two-horse race.

Lap two was a blur of relentless shouting and thundering steps. I felt a warm, spine-tingling sensation run down my back, and I wanted every contrade to win. I was cheering for the Palio itself. All the while, Giraffa was gaining.

During lap three, the lagging riders made desperate maneuvers to close the gap, and Aquila’s jockey was slung from his horse in the wide turn just below our balcony. The horse flipped on the ground, wild-eyed and flailing in the dirt, as medical staff sprinted to secure the jockey, who was thankfully uninjured (nor was his horse hurt, I learned later). On the other side of the Campo, Giraffa and Chiocciola crossed the finish line neck-in-neck: a true photo finish. A day of pageantry and weeks of preparation had culminated in ninety seconds of breathless action.

The result was quickly confirmed—Giraffa had won—and the crowd spilled onto the dusty track. The next few minutes saw a bizarre balancing of turmoil and order, a dance on the border of chaos. Fist-fights broke out while the carabinieri and the polizia looked on dispassionately, studying the scene for any actual danger. A dense crowd of red-and-white giraffe mobbed the winning jockey and carried him from his horse. I could see that the men and women of this victorious contrada were not merely crying but openly weeping, hundreds of fists raised in celebration. I’m not exaggerating when I say that I’ve never witnessed a group of people so happy about anything. It was as if they’d won a war.

The jostling between rival contrade dissipated as people filtered out of the Campo. The supporters of Chiocciola were obviously devastated; they say in Siena you’d rather place last than place second in the Palio. After the race, the other contrade—so present beforehand—seemed to disappear. I saw no flag other than that of Giraffa for the rest of the night. The losers were licking their wounds and perhaps already strategizing for August. For many hours, through the following day and evening, the people of Giraffa marched through Siena carrying the prize, the palio itself, a banner of hand-painted silk commissioned for this unique race of July the 2nd, 2019. Our group shuffled off to dinner, exhausted, and re-lived the race over pici pasta and red wine.

If the Campo is Siena’s heart, then the Palio is its blood. It’s not a vestige of the past but a genuine, living thing. The Palio goes beyond mere sport or petty entertainment, and it lasts far longer than two days in summer. Some of the local youth (not all of whom participate in a contrada) seem less interested in the Palio’s theatrics, appreciating its peculiarities from a distance. At their worst, the contrade are cliquish and harsh, less fraternal and more “fratty,” as we say in the states. At their best, they embody the life-enriching quality of actual—not virtual, not imagined—communities.

Someone told me about an essay on the topic of the Palio, written by an Italian sociologist. I didn’t catch the name of the paper or its author, but the argument was basically psychoanalytic, casting the Palio as a form of ritualized violence, a cultural expression by which aggressive desires are defused or sublimated. Apparently, the crime-rate in Siena is quite low compared to other cities in Italy. Coincidence? The author thinks not; I suspect it’s more complicated.

Thinking it all over, I’m not sure the Palio is something to demonize, idealize, or even understand. The Palio is something that the people of Siena do, and will continue to do, together.

***************

A clip of the race from 2 July 19:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D1gYcIymzU4

A trailer for a 2015 documentary about the Palio: