by Joseph Shieber

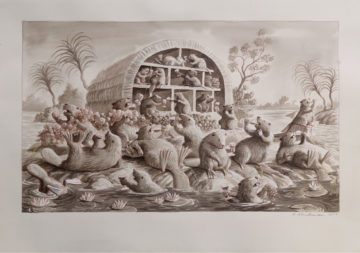

Completely by chance, I happened to come across a discussion of Tyron Goldschmidt’s paper, “A Proof of Exodus: Judah HaLevy and Jonathan Edwards Walk into a Bar”, in Cole Aronson’s review of the 2019 book Jewish Philosophy in an Analytic Age. I was intrigued by Aronson’s celebration of Goldschmidt’s “characteristic verve”, so — with the help of my college’s outstanding Interlibrary Loan — I got hold of the paper.

Just as a matter of literary quality, Aronson undersells Goldschmidt’s paper. Goldschmidt is a delightfully engaging writer. If you’ve dipped into some contemporary academic philosophy and come away with the impression that it’s all turgid and dry, check out Goldschmidt’s essay. It’s a treat.

Now, of course, I’ve got to go ahead and ruin your impression of the delightfulness of academic philosophy by attempting to point out flaws in Goldschmidt’s argument. I can’t help it; it’s in my nature.

Goldschmidt begins by noting that testimony is central to our knowledge. Much of what we know is based on our having learned it from others. If anything, Goldschmidt underappreciates our dependence — the example he uses is historical (our knowledge that Napoleon existed), but he could have easily included countless examples. It’s only because of testimony that I know that Raphael Warnock is a newly-elected U.S. Senator from Georgia, that the top five warmest years on record have been since 2015, or even what my own name is!

Goldschmidt suggests that, by appreciating the centrality of testimony we can appreciate an underrecognized argument for the truth of biblically recorded miracles — in particular, the miracles associated with the Jewish tradition surrounding the Exodus from Egypt. Read more »

The German language is famous for its often long compound words that combine ideas to neatly express in a single word complex notions. Torschlusspanik, (gate-shut-panic), for instance, referred in medieval times to the fear that one was not going to make it back into the city before the gates closed for the night, and now signifies the worry, common among middle aged people, that the opportunities for accomplishing one’s dreams are disappearing for good. Backpfeifengesicht, sometimes translated as “face in need of a fist”, means a face that you feel needs slapping.

The German language is famous for its often long compound words that combine ideas to neatly express in a single word complex notions. Torschlusspanik, (gate-shut-panic), for instance, referred in medieval times to the fear that one was not going to make it back into the city before the gates closed for the night, and now signifies the worry, common among middle aged people, that the opportunities for accomplishing one’s dreams are disappearing for good. Backpfeifengesicht, sometimes translated as “face in need of a fist”, means a face that you feel needs slapping.

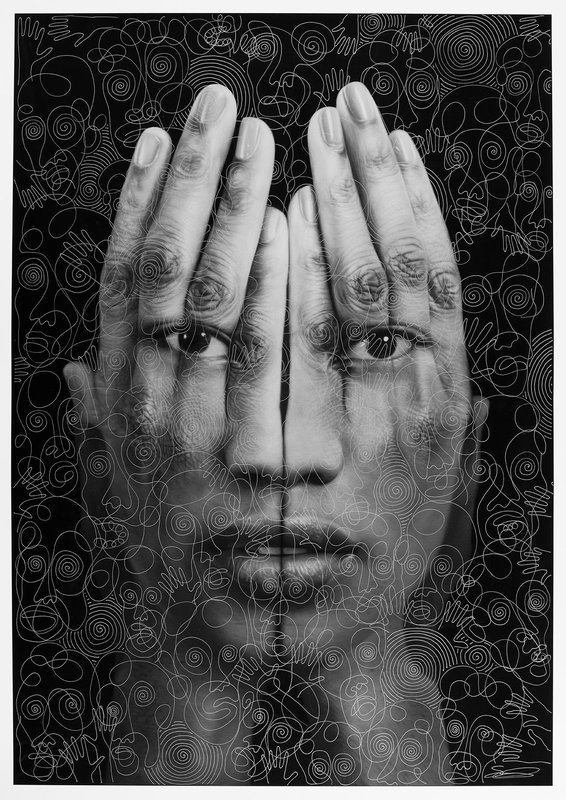

Tigran Tsitoghdzyan. Black Mirror, 2018.

Tigran Tsitoghdzyan. Black Mirror, 2018.

The violent, insurrectionist attack on the US Capitol on January 6, 2021 was due, in part, to the success of the Nation’s system of public education, not its failure. Since Ronald Reagan announced in 1981 that “government is not the solution to our problem, government IS the problem,” federal authorities have worked to dismantle and erase any vestiges of democratic education from our system of public education. Free-market values replaced democratic ones. Public education slowly but consistently was transformed by neoliberal ideologues on both sides of the aisle into an institution both in crisis and the cause of the Nation’s perceived economic slip on the global stage. Following Reagan’s lead, all federally sponsored school reform efforts hollowed out public education’s essential role in a democracy and focused instead on its role within a free-market economy. In terms of both a fix and focus, neoliberalism was and remains the ideological engine that drives the evolution of public education in the United States. These reform efforts have been incredibly successful in reducing public education to a general system of job training, higher education prep, and ideological indoctrination (i.e., American Exceptionalism). As a consequence of this success, many of the Nation’s citizens have little to no knowledge or skills relating to the essential demands of democratic life. The culmination of the neoliberal assault on democratic education over the last forty-years helped create the conditions that led to the rise of Trump, the development of Trumpism, and the murderous, failed attempt at a coup d’etat in Washington, DC. From what I have read, I am not confident that your plans for public education will address these issues.

The violent, insurrectionist attack on the US Capitol on January 6, 2021 was due, in part, to the success of the Nation’s system of public education, not its failure. Since Ronald Reagan announced in 1981 that “government is not the solution to our problem, government IS the problem,” federal authorities have worked to dismantle and erase any vestiges of democratic education from our system of public education. Free-market values replaced democratic ones. Public education slowly but consistently was transformed by neoliberal ideologues on both sides of the aisle into an institution both in crisis and the cause of the Nation’s perceived economic slip on the global stage. Following Reagan’s lead, all federally sponsored school reform efforts hollowed out public education’s essential role in a democracy and focused instead on its role within a free-market economy. In terms of both a fix and focus, neoliberalism was and remains the ideological engine that drives the evolution of public education in the United States. These reform efforts have been incredibly successful in reducing public education to a general system of job training, higher education prep, and ideological indoctrination (i.e., American Exceptionalism). As a consequence of this success, many of the Nation’s citizens have little to no knowledge or skills relating to the essential demands of democratic life. The culmination of the neoliberal assault on democratic education over the last forty-years helped create the conditions that led to the rise of Trump, the development of Trumpism, and the murderous, failed attempt at a coup d’etat in Washington, DC. From what I have read, I am not confident that your plans for public education will address these issues.

Philosophy has been an ongoing enterprise for at least 2500 years in what we now call the West and has even more ancient roots in Asia. But until the mid-2000’s you would never have encountered something called “the philosophy of wine.” Over the past 15 years there have been several monographs and a few anthologies devoted to the topic, although it is hardly a central topic in philosophy. About such a discourse, one might legitimately ask why philosophers should be discussing wine at all, and why anyone interested in wine should pay heed to what philosophers have to say.

Philosophy has been an ongoing enterprise for at least 2500 years in what we now call the West and has even more ancient roots in Asia. But until the mid-2000’s you would never have encountered something called “the philosophy of wine.” Over the past 15 years there have been several monographs and a few anthologies devoted to the topic, although it is hardly a central topic in philosophy. About such a discourse, one might legitimately ask why philosophers should be discussing wine at all, and why anyone interested in wine should pay heed to what philosophers have to say.

Every Democrat, and many independent voters, breathed an enormous sigh of relief when Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump in the November election. Now they are all nervously counting down the days (16) until the last of Trump’s frivolous lawsuits is dismissed, his minions’ stones bounce of the machinery of our electoral system, and Trump is finally evicted from the White House. Only then can we set about repairing the very significant damage that Trump and Trumpism have wrought upon our republican (small r) and democratic (small d) institutions.

Every Democrat, and many independent voters, breathed an enormous sigh of relief when Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump in the November election. Now they are all nervously counting down the days (16) until the last of Trump’s frivolous lawsuits is dismissed, his minions’ stones bounce of the machinery of our electoral system, and Trump is finally evicted from the White House. Only then can we set about repairing the very significant damage that Trump and Trumpism have wrought upon our republican (small r) and democratic (small d) institutions. Three times have we started doing philosophy, and three times has the enterprise come to a somewhat embarrassing end, being supplanted by other activities while failing anyway to deliver whatever goods it had promised. Each of those three times corresponds to a part of Stephen Gaukroger’s recent book The Failures of Philosophy, which I will be discussing here. In each of these three times, philosophy’s program was different: in Antiquity, it tied itself to the pursuit of the good life; after its revival in the European middle ages it obtained a status as the guardian of a fundamental science in the form of metaphysics; and when this metaphysical project disintegrated, it reinvented itself as the author of a meta-scientific theory of everything, eventually latching on to science in a last attempt at relevance.

Three times have we started doing philosophy, and three times has the enterprise come to a somewhat embarrassing end, being supplanted by other activities while failing anyway to deliver whatever goods it had promised. Each of those three times corresponds to a part of Stephen Gaukroger’s recent book The Failures of Philosophy, which I will be discussing here. In each of these three times, philosophy’s program was different: in Antiquity, it tied itself to the pursuit of the good life; after its revival in the European middle ages it obtained a status as the guardian of a fundamental science in the form of metaphysics; and when this metaphysical project disintegrated, it reinvented itself as the author of a meta-scientific theory of everything, eventually latching on to science in a last attempt at relevance.

For the past few years, I’ve been taking a fairly deep dive into attempting to understand the physical and ecological changes occurring on our planet and how these will affect human lives and civilization. As I’ve immersed myself in the science and the massive societal hurdles that stand in the way of an adequate response, I’m becoming aware that this exercise is changing me, too. I feel it inside my body, like a grey mass coalescing in my chest, sticking to everything, tugging against my heart and occluding my lungs. A couple of months ago, I decided to stop writing on this subject, to step away from these thoughts and concerns, because of their discomfiting darkness.

For the past few years, I’ve been taking a fairly deep dive into attempting to understand the physical and ecological changes occurring on our planet and how these will affect human lives and civilization. As I’ve immersed myself in the science and the massive societal hurdles that stand in the way of an adequate response, I’m becoming aware that this exercise is changing me, too. I feel it inside my body, like a grey mass coalescing in my chest, sticking to everything, tugging against my heart and occluding my lungs. A couple of months ago, I decided to stop writing on this subject, to step away from these thoughts and concerns, because of their discomfiting darkness.

If one enters the name “Ellen Page” into the search box at

If one enters the name “Ellen Page” into the search box at