by Usha Alexander

[This is the eighth in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

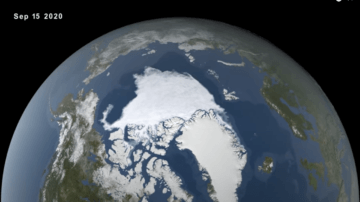

In the late fifteenth century, European seafarers began searching for what they called the “Northwest Passage,” a fabled route across the Arctic Ocean, which would allow them to sail northward from Europe directly into the Pacific in search of fortune. But the Arctic of their time, during the so-called Little Ice Age of the fourteenth to mid-nineteenth centuries, was covered by thick, impenetrable sheets of ice and densely packed icebergs. Nor had they any reasonable expectation that the great mass of ice would soon melt away. That they imagined finding a reliably navigable route through a polar sea seems to me a case of wishful thinking, a folly upon which scores of lives and fortunes were staked and lost, as so many adventurers attempted crossings, only to flounder and often die upon the ice.

In the late fifteenth century, European seafarers began searching for what they called the “Northwest Passage,” a fabled route across the Arctic Ocean, which would allow them to sail northward from Europe directly into the Pacific in search of fortune. But the Arctic of their time, during the so-called Little Ice Age of the fourteenth to mid-nineteenth centuries, was covered by thick, impenetrable sheets of ice and densely packed icebergs. Nor had they any reasonable expectation that the great mass of ice would soon melt away. That they imagined finding a reliably navigable route through a polar sea seems to me a case of wishful thinking, a folly upon which scores of lives and fortunes were staked and lost, as so many adventurers attempted crossings, only to flounder and often die upon the ice.

But now that the Arctic sea ice is melting away, the Northwest Passage has become real in a way the adventurers of old could not have dreamed. Today, nations encircling the Arctic Ocean jockey for control of its waters and territorial rights to newly exposed northern continental shelves, which promise to be full of oil and gas. What had been a deadly fantasy is now a luxury cruise destination flaunting an experience of rare wonder, including opportunities to watch polar bears on the hunt. “A journey north of the Arctic Circle is incomplete without observing these powerful beasts in the wild,” entices the Silversea cruises website, with nary a note about the bears’ existence being threatened by the very disintegration of their icy habitat that makes this wondrous cruise possible. Meanwhile, in China, the emergent northern sea routes have been dubbed the Polar Silk Road, projecting a powerful symbol of their past wealth and influence onto an unprecedented reality.

By now, we’re all aware that the planet is profoundly changing around us: angrier weather, retreating glaciers, flaming forests, bleaching coral reefs, starving polar bears, disappearing bees. Yet how blithely we go on making plans, as though the future will follow as neatly and predictably from today, as today did from yesterday. From buying a new beachside home to booking a cabin in the redwoods a year in advance, the ongoing planetary changes apparently figure little in the plans so many people make. It seems I regularly read articles in which mainstream economists make predictions that entirely disregard the changing climate and collapsing biodiversity, as though these concerns lie beyond our economies. Even governments and corporations who seek to profit from changes like the opening of the Arctic Ocean often presume themselves the drivers of “disruption,” creating new market opportunities in an otherwise stable or predictable world. They don’t seem to recognize that the true nature of what’s upon us might just be greater than they imagine and far more consequential. Read more »

In the summer of 1977 my father invited me to tea at the Hotel Grande Bretagne in Athens. I had turned 13 that spring, and instead of a bar mitzvah, prohibited by matrilineal descent and an antipathy to organized religion, my father and I were en route to Israel, to visit the kibbutz where he had worked in the mid-1950s. We had flown from Vancouver to Amsterdam, proceeded by train to Rome, and continued by rail across Italy to Brindisi, by ferry to Patras, and by coach to Athens. From there we would eventually embark, at Piraeus, on the crossing to Haifa; for the moment we were enjoying some sightseeing in the Greek capital.

In the summer of 1977 my father invited me to tea at the Hotel Grande Bretagne in Athens. I had turned 13 that spring, and instead of a bar mitzvah, prohibited by matrilineal descent and an antipathy to organized religion, my father and I were en route to Israel, to visit the kibbutz where he had worked in the mid-1950s. We had flown from Vancouver to Amsterdam, proceeded by train to Rome, and continued by rail across Italy to Brindisi, by ferry to Patras, and by coach to Athens. From there we would eventually embark, at Piraeus, on the crossing to Haifa; for the moment we were enjoying some sightseeing in the Greek capital.

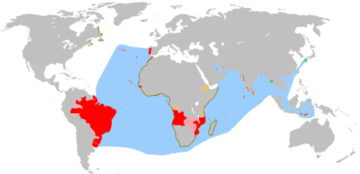

I’ve long been partial to Portuguese culture, so when Portugal transferred its last colonial holding, Macau, back to Chinese rule in 1999 , a friend surprised me with his marveling reaction: “Portugal had an empire? Who knew?”

I’ve long been partial to Portuguese culture, so when Portugal transferred its last colonial holding, Macau, back to Chinese rule in 1999 , a friend surprised me with his marveling reaction: “Portugal had an empire? Who knew?” The Portuguese initiated the transatlantic slave trade in 1444, which has bedeviled and tormented much of the world ever since. Sixty years later, the Viceroy Alfonso Albuquerque expanded Portuguese power not only as exploration for economic reasons, but as a brutal crusade against Islam. By 1580, the empire extended from Brazil to Africa, from India to Malaysia and on to the Indonesian island of Timor.

The Portuguese initiated the transatlantic slave trade in 1444, which has bedeviled and tormented much of the world ever since. Sixty years later, the Viceroy Alfonso Albuquerque expanded Portuguese power not only as exploration for economic reasons, but as a brutal crusade against Islam. By 1580, the empire extended from Brazil to Africa, from India to Malaysia and on to the Indonesian island of Timor.

White Americans get a lot of things wrong about race. And not just the relatively small number of blatant white supremacists, or the many millions (

White Americans get a lot of things wrong about race. And not just the relatively small number of blatant white supremacists, or the many millions (

Not long ago, a reader complained, politely but firmly, about your humble author’s regrettable tendency to post something called “Blah blah blah pt. 1” and then never get back to it for part two, in particular the post about history, wondering if possibly I thought no one would notice that I had left it hanging. I admit the fault, but I assure my patient reader, or possibly readers, that I do indeed intend to finish each and every one of my multipart posts, and even to make clear how they are related to each other. (That’s the intent, anyway.) So fear not! (I do have to read some more history though … !) This time, though, I finish a different sort of multipart post: my end-of-2020 podcast. Plenty of unfamiliar names, even to me, but some great stuff! As always, widget and/or link below.

Not long ago, a reader complained, politely but firmly, about your humble author’s regrettable tendency to post something called “Blah blah blah pt. 1” and then never get back to it for part two, in particular the post about history, wondering if possibly I thought no one would notice that I had left it hanging. I admit the fault, but I assure my patient reader, or possibly readers, that I do indeed intend to finish each and every one of my multipart posts, and even to make clear how they are related to each other. (That’s the intent, anyway.) So fear not! (I do have to read some more history though … !) This time, though, I finish a different sort of multipart post: my end-of-2020 podcast. Plenty of unfamiliar names, even to me, but some great stuff! As always, widget and/or link below. Do you have a right to own a microwave oven? To be clear, ideally in a free society, absent a clear showing of harm to others, there’s a presumption that you can do whatever you want and own whatever you can make or buy. So, you do have a basic right to own things – to acquire property, as political philosophers like to say. But it’s consistent with that right for there to be a lot of rules and regulations around what you can own – and even prohibitions on owning certain kinds of things.

Do you have a right to own a microwave oven? To be clear, ideally in a free society, absent a clear showing of harm to others, there’s a presumption that you can do whatever you want and own whatever you can make or buy. So, you do have a basic right to own things – to acquire property, as political philosophers like to say. But it’s consistent with that right for there to be a lot of rules and regulations around what you can own – and even prohibitions on owning certain kinds of things.

For those of us who classify ourselves as Nones—

For those of us who classify ourselves as Nones—