by Thomas R. Wells

by Thomas R. Wells

Libertarianism does not make sense. It cannot keep its promises. It has nothing to offer. It is an intellectual failure like Marxism or Flat-Earthism – something that might once reasonably have seemed worth pursuing but whose persistence in public let alone academic conversation has become an embarrassment. The only mildly interesting thing about libertarianism anymore is why anyone still takes it seriously.

When evaluating a normative ethical theory we should consider three dimensions:

- Is the theory plausible in its own right? I.e. does it make sense or is it an incoherent mess of contradictions?

- Would the world be better if it was ordered according to the theory? I.e. does the theory promise us anything worth having?

- Does the theory provide a useful guide to action around here right now? I.e. is it any help at all for addressing the kind of problems that actually appear in our practical moral and political life?

1. Does Libertarianism Make Sense?

Libertarianism is a response to the problem of politics – the sphere of activity concerned with the collective management of our social living arrangements that is complicated, contingent, and refuses to obey the authority of reason. The problem of politics has offended many philosophers from Plato onwards. Libertarians’ particular solution to the problem is what I call eliminative moralism: the reduction of the entire noisome political sphere to its supposed basis in a narrow interpersonal morality of consent. The result has an extraordinary intellectual simplicity and normative minimalism which many find appealing and convenient, yet the very sources of its appeal are its deepest flaws. Read more »

We both have daughters who are good at math, but opted out of advanced math. In so doing, they effectively closed off entry into math-intensive fields of study at university such as physics, engineering, economics, and computer science. They used to be enthusiastic about math, but as early as grade three this enthusiasm waned, and they weren’t alone. It was a pattern we observed repeatedly in their female friends during those early school years, as boys slowly inched ahead.

We both have daughters who are good at math, but opted out of advanced math. In so doing, they effectively closed off entry into math-intensive fields of study at university such as physics, engineering, economics, and computer science. They used to be enthusiastic about math, but as early as grade three this enthusiasm waned, and they weren’t alone. It was a pattern we observed repeatedly in their female friends during those early school years, as boys slowly inched ahead.

Here is a hardy perennial: Are human beings naturally indolent? From sagacious students of human nature there is no shortage of opinions.

Here is a hardy perennial: Are human beings naturally indolent? From sagacious students of human nature there is no shortage of opinions.

Epistenology: Wine as Experience

Epistenology: Wine as Experience

The disappointing new film

The disappointing new film  Both morally and politically, equality is a powerful ideal. Over the last two centuries it has been one of the fundamental demands of most movements aimed at improving society. The French Revolution is the paradigm case. Despite its enduring relevance, however, equality has always been a somewhat vague ideal. It was hardly a problem for the revolutionaries in France, where the difference between the aristocracy and the sans-culottes was so stark that further elaboration was unnecessary. Over the years, however, the question ‘equality of what?’ has become more pressing, and many answers have been highlighted: equal rights, equal pay, equal treatment, equal opportunities, equality under the law, equality of outcome, to name but a few. Rather than just looking at these answers, perhaps we should start by identifying the source of the ideal of equality’s ethical power, and see where this leads us.

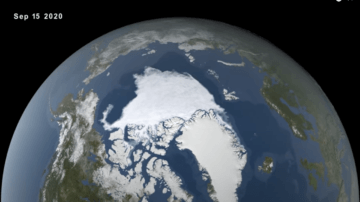

Both morally and politically, equality is a powerful ideal. Over the last two centuries it has been one of the fundamental demands of most movements aimed at improving society. The French Revolution is the paradigm case. Despite its enduring relevance, however, equality has always been a somewhat vague ideal. It was hardly a problem for the revolutionaries in France, where the difference between the aristocracy and the sans-culottes was so stark that further elaboration was unnecessary. Over the years, however, the question ‘equality of what?’ has become more pressing, and many answers have been highlighted: equal rights, equal pay, equal treatment, equal opportunities, equality under the law, equality of outcome, to name but a few. Rather than just looking at these answers, perhaps we should start by identifying the source of the ideal of equality’s ethical power, and see where this leads us. In the late fifteenth century, European seafarers began searching for what they called the “Northwest Passage,” a fabled route across the Arctic Ocean, which would allow them to sail northward from Europe directly into the Pacific in search of fortune. But the Arctic

In the late fifteenth century, European seafarers began searching for what they called the “Northwest Passage,” a fabled route across the Arctic Ocean, which would allow them to sail northward from Europe directly into the Pacific in search of fortune. But the Arctic

In the summer of 1977 my father invited me to tea at the Hotel Grande Bretagne in Athens. I had turned 13 that spring, and instead of a bar mitzvah, prohibited by matrilineal descent and an antipathy to organized religion, my father and I were en route to Israel, to visit the kibbutz where he had worked in the mid-1950s. We had flown from Vancouver to Amsterdam, proceeded by train to Rome, and continued by rail across Italy to Brindisi, by ferry to Patras, and by coach to Athens. From there we would eventually embark, at Piraeus, on the crossing to Haifa; for the moment we were enjoying some sightseeing in the Greek capital.

In the summer of 1977 my father invited me to tea at the Hotel Grande Bretagne in Athens. I had turned 13 that spring, and instead of a bar mitzvah, prohibited by matrilineal descent and an antipathy to organized religion, my father and I were en route to Israel, to visit the kibbutz where he had worked in the mid-1950s. We had flown from Vancouver to Amsterdam, proceeded by train to Rome, and continued by rail across Italy to Brindisi, by ferry to Patras, and by coach to Athens. From there we would eventually embark, at Piraeus, on the crossing to Haifa; for the moment we were enjoying some sightseeing in the Greek capital.

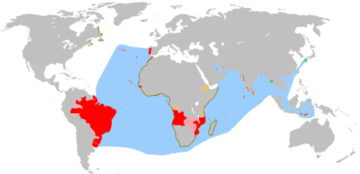

I’ve long been partial to Portuguese culture, so when Portugal transferred its last colonial holding, Macau, back to Chinese rule in 1999 , a friend surprised me with his marveling reaction: “Portugal had an empire? Who knew?”

I’ve long been partial to Portuguese culture, so when Portugal transferred its last colonial holding, Macau, back to Chinese rule in 1999 , a friend surprised me with his marveling reaction: “Portugal had an empire? Who knew?” The Portuguese initiated the transatlantic slave trade in 1444, which has bedeviled and tormented much of the world ever since. Sixty years later, the Viceroy Alfonso Albuquerque expanded Portuguese power not only as exploration for economic reasons, but as a brutal crusade against Islam. By 1580, the empire extended from Brazil to Africa, from India to Malaysia and on to the Indonesian island of Timor.

The Portuguese initiated the transatlantic slave trade in 1444, which has bedeviled and tormented much of the world ever since. Sixty years later, the Viceroy Alfonso Albuquerque expanded Portuguese power not only as exploration for economic reasons, but as a brutal crusade against Islam. By 1580, the empire extended from Brazil to Africa, from India to Malaysia and on to the Indonesian island of Timor.